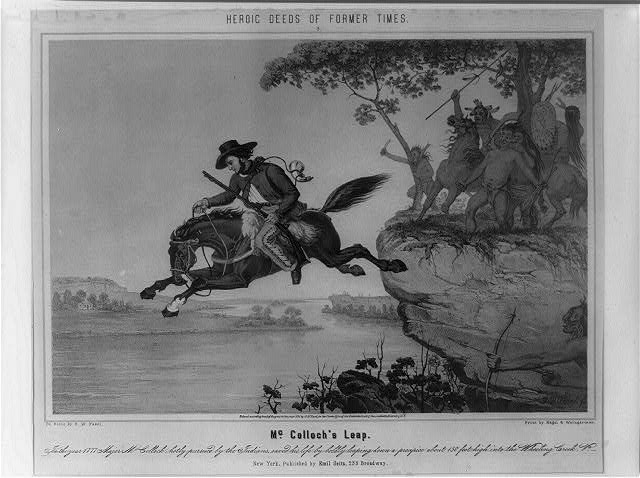

“By no means comparable with the feats of a similar character” and “performed an act of daring” and “nay, desperate horsemanship” and “seldom been equaled by man or beast.” All these describe the amazing escape of Major Samuel McColloch in September 1777 during the attack on Fort Henry around where present-day Wheeling, West Virginia.

I first encountered this amazing, daring, and crazy eluding of capture when I took my own, well not as risky, but still a leap, moving to Wheeling to attend university there. Parents were 3,000 miles away in England and I was attempting to juggle basketball, studies, getting re-acclimated to life in the United States, and unknowingly, a left knee that was about to explode. Being a history major, this was one of the first accounts learned in a freshman year seminar class about local history to inspire the incoming students to explore the area outside of campus.

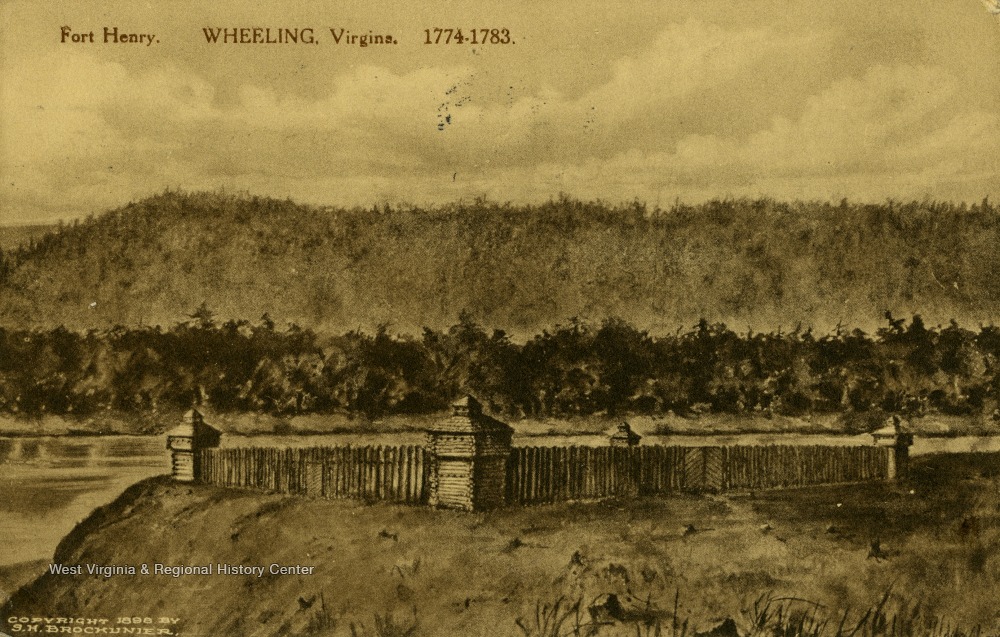

Fort Henry, built in 1774, was originally named Fort Fincastle, one of the titles of Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia. When the colonies revolted, the fortification was renamed in honor of Patrick Henry.

courtesy of West Virginia History OnView

https://wvhistoryonview.org/catalog/041457

In the late summer and early autumn of 1777, Shawnee, Wyandot, and Mingo Native Americans unleashed attacks on American settlers throughout the Ohio Valley. Militia from scattered posts congregated in Fort Henry and vowed to withstand the Native American onslaught. One of the last reinforcing troops was a 40-man contingent under the command of Major Samuel McColloch.

As the gates opened to welcome the reinforcements, McColloch circled to the back of the cavalcade, making sure all his men would be accounted for and taking the post of most danger. With the Native Americans approaching rapidly, McColloch was unable to follow his troops into Fort Henry and the gates closed with him between the walls and the enemy.

Knowing that capture meant certain torture, especially with being well-known as a vigilant and deadly enemy of the Native Americans, McColloch used his expert horsemanship on a dash up a bordering hillside, known as Wheeling Hill. Instead of eluding his pursuers he unexpectedly encountered another band of Native Americans which had effectively hemmed him in.

With the enemy on three sides and a sharp precipice on the fourth, McColloch seemed out of options. Not wanting to face the wrath of being taken prisoner, he took a leap of faith. Grasping the bridle in his left and holding a death-grip on is rifle with the other, he urged the mount toward the edge. He careened off the edge, approximately 300 feet high. Enemy warriors rushed to the edge, believing that they would see a dead McColloch at the base of the hill.

Instead, they saw a mounted McColloch dashing off into the distance. Riding into history and local legendary status.

Now that you know about the famous leap, next time traveling through the northern panhandle of West Virginia, take a small detour and ride past the marker and take a moment to admire this “act of daring” on the western frontier of the American Revolution.

courtesy of Ohio County Public Library Archives

This story sounds a lot like the “slide” of Major Robert Rogers from what’s now called Rogers Rock on to the ice covered surface Lake George after he and his command were defeated at the second battle on snowshoes in 1758. A great story with little validity.

LikeLike

Good point Bruce, one must take these types of accounts with a grain of salt.

LikeLike

First a disclaimer: I am a direct descendent of Samuel McColloch’s younger brother Abram and so cannot deny a bias. I will use my spelling of the name, but being a Scot’s Celtic name it has been fluid so McCulloch and even McCullough have been used through family history. I am also a recently retired field geologist and principle author of the most recent geologic map of the Wheeling 7.5 Minute Quadrangle so my interpretation of the real nature of the unmodified slope should have some credibility.

Samuel and older brother John were on patrol from Fort Van Meter on Short Creek near the current location of Clinton, WV later in 1777 when they were attacked by a band of warriors, who killed Samuel, although the target of that attack might have been John. John escaped to the fort and returned with a party the next day to find Samuel’s body with the heart removed. Later they learned that the party had divided the heart and a number of warriors ate a small piece. As the tribes of the region were not cannibals this was unusual and indicated unusual respect for the deceased’s bravery, hoping to retain some for themselves. Some of the warriors in this band had probably been at Wheeling Hill, less than eight miles from where the ambush occurred, and witnessed the “leap”. Samuel was already known as a brave man, but it is at least possible that this recent event cemented his bravery in the minds of his worthy adversaries.

Below you will find a link to a historical account of that story:

http://www.wvculture.org/history/settlement/mcculloch01.html

As to the “leap” the geomorphic history of this part of the upper Ohio Valley is unique in that the adjacent segment of the river, now known as part of the Ohio but formerly part of the northward flowing Ontario River, has reversed course in the geologically recent past as the result of glaciation. The Ohio is a much larger river system and the stream gradient changed. That in turn resulted in an unusual amount of erosion in places like the cut bank area where the “leap” was reported to have occurred. The slope is steep, but has only a little over 200 feet of total relief not 300. The hill is primarily composed of fresh to brackish water limestones, shales, and includes the Pittsburgh Coal (at the level of the Interstate70 tunnel), extensive under-clay, and an overlying sandstone. All of these bedrock types are known to weather quickly particularly as they were being undercut by Wheeling Creek. At the top was possibly a small drop-off at the sandstone level, but it could have been covered by loess derived and blown in from continental glaciers to the north that has been observed to the north in Ohio. My overall visualization of the slope at the time is one of coalescing colluvial fans composed of relatively small pieces of soft material that would roll under the weight of a horse and rider allowing a controlled slide for a well trained horse. The McColloch’s were known to be some of the most accomplished horsemen of the time in the upper Ohio Valley so Samuel McColloch’s “leap” is, at least, credible from the standpoint of regional geomorphology. I also imagine that Samuel had examined the slope prior to his “leap”.

The slope of Samuel’s time is probably no longer present and was likely gentler that today’s slope as the lens of colluvial material was probably removed and used for fill material for one or more of the numerous nearby sites as Wheeling industrialized leaving the slope we see today.

LikeLike

Who knows…if the circumstances hadn’t been so dire, he might have invented an extreme sport two centuries before the X-Games!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, Part 2 | Emerging Revolutionary War Era

Pingback: Rosecrans, Fremont HQ For Sale… | Emerging Civil War

Pingback: McColloch’s Leap and Other Wheeling Wayside Adventures | Archiving Wheeling

Thanks for this blog postt

LikeLike