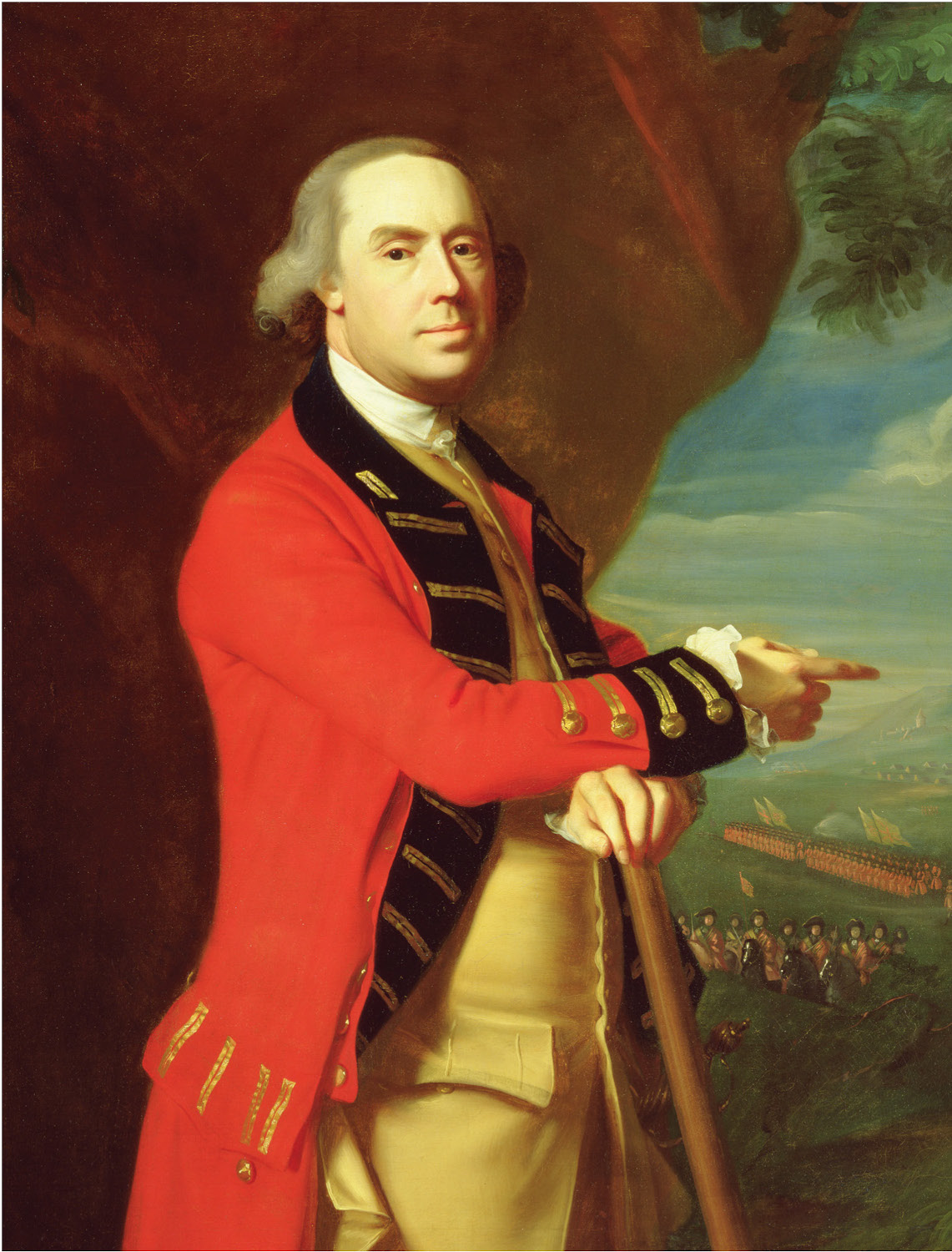

On May 13, 1774, the newly Royally appointed Governor of Massachusetts arrived in Boston. General (and now Governor) Thomas Gage was well known to the American colonists. Gage served as a Major in the 44th Regiment of Foot in the French and Indian War, most notably in the Battle of the Monongahela. When several of Gage’s officers fell, he took up temporary command of the 44th during the battle. During that time Gage got to know George Washington and both men respected each other. After the war, Gage received a promotion to Brigadier General and was appointed the military governor of Montreal.

Soon after, Gage became the commander in chief of all British forces in North America. He moved to New York city to administer the King’s forces in the American colonies. Gage’s popularity increased as he focused on creating peace with the Indian population along the new western border of the colonies through various treaties. Gage and his American born wife, Margaret, were well accepted into New York society. Gage always believed that the democratic spirit that pervaded the colonies were a threat to British rule. With many of the colonists accustomed to electing their own representation, he believed this created more division with the home country than making them British citizens. Gage had long believed that democracy was too rooted in colonial society. In 1772 he wrote “democracy is too prevalent in America.”

As tensions began to increase within the American colonies, Gage’s response exasperated the situation. He contracted many of the British military posts back to the colonial cities along the eastern seaboard (which in part led to the Boston Massacre in 1770). He believed a show of military strength would help put out the fires of discontent. Further, he concluded that the unrest was mostly pushed by a very small minority, not the vast majority of colonials. He underestimated how the masses would respond to his hard hand. Now Gage, who was in Great Britain when the news of the Boston Tea Party arrived, was seen as a great fit to handle the crisis in Boston. His military back ground and experience as a civil leader (and liked by many in the colonies) made him on paper an ideal candidate for Governor of Massachusetts in this unsettled time.

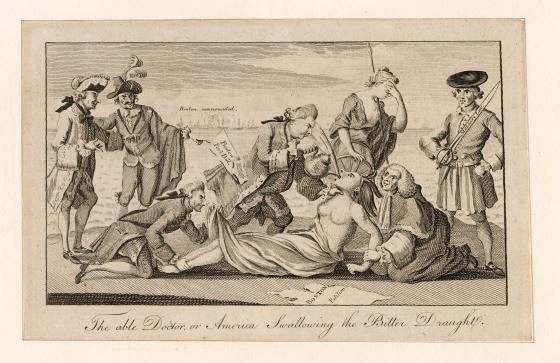

Many in Boston welcomed Gage when he arrived that May. Mostly because they had become so disenchanted with former Governor Thomas Hutchinson, who was completely not up to the task that faced him in 1773. The recently passed Boston Port Act (passed in March 1774, this act closed the port of Boston until the loss of the tea was paid for) grew tensions in Boston, but large segments of the population believed that those that destroyed the tea should pay for it. Soon, it was the next piece of news from Great Britain that shook the foundation of something the majority of Bay Staters took pride in, self-rule.

Word arrived of two new laws recently passed on May 20, 1774, Parliament passed the Massachusetts Government Act and Impartial Administration of Justice Act. These two acts were punitive in measure and sought to bring the colony under direct Royal control. The Government Act stated “Parliament passes this act turning the Massachusetts Council into a body of crown appointees“ (similar to other Royal colonies like Virginia) when up to then they were elected. Also, it restricted the traditional “town meeting” to just one a year. Town meetings were an essential local governing tool to not just govern localities but also to provide open communication across the colony. The Justice Act gave the governor the power to a trial to another colony or to Great Britain if he determined “that an indifferent trial cannot be had within the said province.” Judgment by one’s peers was a long-standing tradition in Massachusetts and in British law dating back to the Magna Carta. These measures essentially dissolved important aspects of the Massachusetts Charter of 1691.

Furthermore, Gage inflamed the situation more in Boston by bringing with him more British Regular troops. By the end of 1774, Gage had more than 4,000 soldiers in and around Boston. Gage could see the situation worsening but was unable to determine how to best deal with what confronted him. Whig leaders such as Dr. Joseph Warren, Paul Revere and Samuel Adams used these newly passed acts as proof that Great Britain was infringing on their rights and liberties. Using groups like the Sons of Liberty, Whig leaders began to gain great influence as many of the colonists began to turn against Great Britian. Soon many of these community organizations began to arm themselves and coordinate with the other colonies via committees of correspondence. Gage, feeling the situation was becoming dangerous wrote back to authorities in Great Britain “Affairs here are worse than even in the Time of the Stamp Act, I don’t mean in Boston, for throughout the Country. The New England Provinces…are I may say in Arms.” Events were beginning to build towards armed revolution, not just in Massachusetts, but across a more unified American colonies.