Continental General Richard Montgomery huddled over his desk outside the walled city of Quebec, clinging to candlelight as he wrote a letter to his wife. Wind howled and snow pelted the Continental forces preparing to attack the city on the St. Lawrence River. “I wish it were well over with all my heart, and I sigh for home like a New Englander,” Montgomery confessed to his wife, Janet. He had come a long way over the last few months—and even farther over the course of his life.

Like a New Englander, Montgomery wrote. Despite his rank in the Continental Army, he was no New Englander, but an Old Englander. His path to becoming an American hero resembled that of several Revolutionary leaders. Like George Washington, Horatio Gates, and others, Montgomery had served in the British Army during the French and Indian War. His road to an American generalship, however, was far from straightforward. Indeed, he was a latecomer to the American cause.

After receiving an education in his native Ireland, Montgomery joined the British Army as an ensign in the 17th Regiment of Foot. He fought in northern New York and Canada during the French and Indian War, later serving as a regimental adjutant in the West Indies, where his service earned him a promotion to captain. After the war, he returned to England, though he grew dissatisfied with life there. His time was not wasted, however; he attracted the attention of British opposition statesman Edmund Burke. Eventually, Montgomery sold his officer’s commission and emigrated to North America. On July 24, 1773, he purchased 67 acres of farmland at King’s Bridge, New York—now a neighborhood in the Bronx.

Montgomery’s passion for farming marked his transition to civilian life. Shortly after resettling in America, he married into the strongly anti-British Livingston family. The influence of his in-laws—and perhaps that of his wife, Janet—helped alter the trajectory of his life. In May 1775, Montgomery received an appointment to New York’s first Provincial Congress. A month later, he became a Continental general, though, as historian Mark M. Boatner III noted, he accepted the post “with personal regret.”

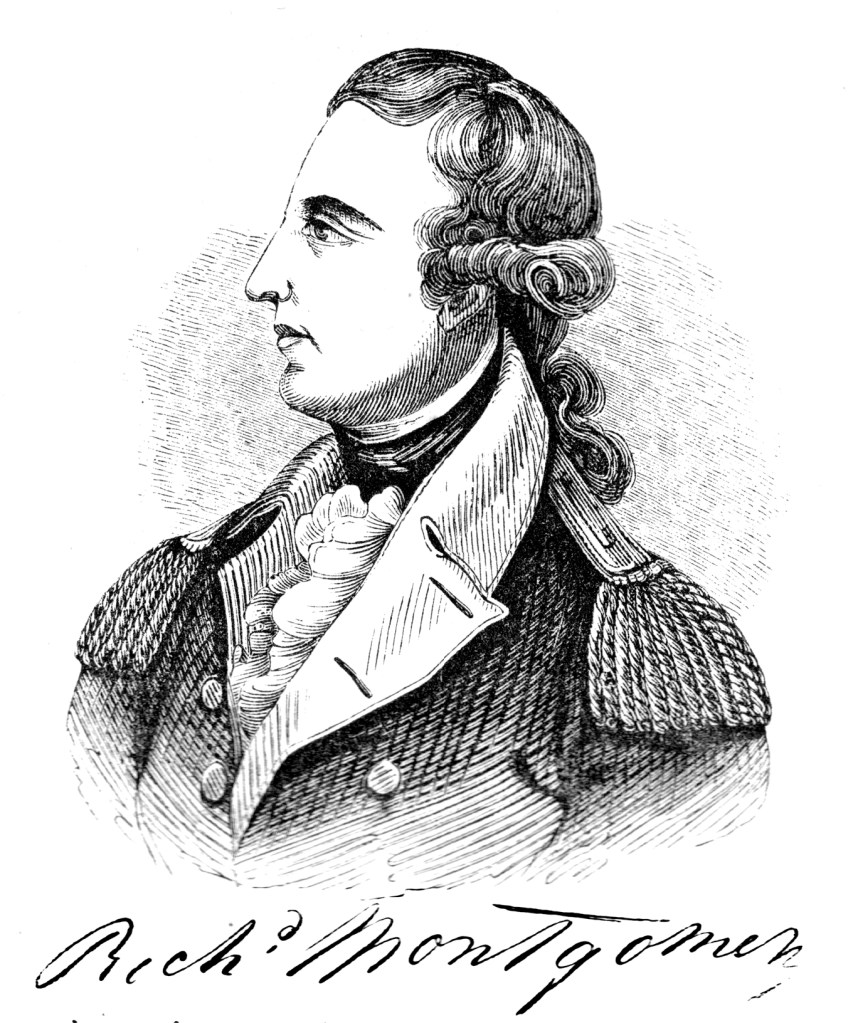

When Montgomery assumed command of American forces invading Canada in early fall 1775, he presented a striking military figure despite having exchanged the sword for the plow. He was described as “tall, of fine military presence, of graceful address, with a bright, magnetic face, winning manners ….” Under his supervision, American forces captured St. Johns and Montreal before linking up with Benedict Arnold outside Quebec on December 2.

Unable to besiege the heavily fortified city or bluff the garrison into surrender—and with enlistments nearing expiration—Montgomery resolved to assault Quebec. The long campaign and worsening winter weather no doubt intensified his longing for home as he organized his portion of the attack on the frigid morning of December 31, 1775.

While diversionary feints distracted the British garrison, Montgomery and Arnold planned to lead separate storming columns against Lower Quebec. Sir Guy Carleton, the British commander, knew that Lower Town was his weak point and had fortified it with cannon, palisades, and blockhouses.

Under the cover of darkness on December 31, Montgomery and Arnold led their respective columns forward. Montgomery’s 300 men advanced along the ice-choked banks of the St. Lawrence River. Freezing wind bit at exposed skin as driving snow stung their eyes. Those carrying the scaling ladders faced a particularly grueling march over rocks, ice, and snow-covered roads.

The pioneers at the head of Montgomery’s column sawed through the first palisade, and the general personally led the advance. At the next barrier, Montgomery took up a saw himself, cutting an opening just wide enough for him and the men behind him to squeeze through. A blockhouse loomed ahead, but as far as he could tell, no British troops yet opposed their progress. Montgomery drew his sword and urged his men forward.

One hundred paces. Seventy-five. Then fifty. Suddenly, flame and smoke erupted from the blockhouse as British grapeshot tore through the howling wind and snow. The blast ripped through the American column. When the smoke cleared, Montgomery lay dead in the snow, grapeshot having struck him in the head, with a dozen of his men fallen behind him. It was well over with Montgomery’s heart—and it was over quickly.

The surviving officers halted the assault and withdrew, leaving the general’s body where it fell. Arnold’s column also failed, and British forces retained control of Quebec.

In death, Montgomery became one of the earliest martyrs of the American cause. Philip Schuyler, who had ceded command of the expedition to him, informed the Continental Congress and George Washington, “My amiable friend, the gallant Montgomery, is no more.” Washington lamented, “In the death of this gentleman, America has sustained a heavy loss, as he had approved himself a steady friend to her rights and of ability to render her the most essential services.” Montgomery’s name soon appeared in American literature as a rallying symbol for the Patriot cause.

British soldiers recognized Montgomery’s remains and buried him with respect on January 4, 1776. His mourners were not limited to America. In Parliament, Edmund Burke praised “the movements of the hero who in one campaign had conquered two thirds of Canada.” Prime Minister Lord Frederick North replied, “He was brave, he was able, he was humane, he was generous; but still he was only a brave, able, humane, and generous rebel.” Charles Fox retorted, “The term of rebel is no certain mark of disgrace. The great asserters of liberty, the saviors of their country, the benefactors of mankind in all ages have been called rebels.” The London Evening Post even bordered its March 12, 1776, edition in black in Montgomery’s honor.

In 1818, the state of New York reinterred Montgomery’s remains in his adopted homeland. Today, they rest in St. Paul’s Chapel in Manhattan beside a monument authorized by the Continental Congress on January 25, 1776, commemorating a general mourned on both sides of the Atlantic.

Pingback: On this day 250 years ago in the Revolution — January 4, 1776 – On This Day In The Revolution

Pingback: On this day 250 years ago in the Revolution — January 25,1776 – On This Day In The Revolution