I spent last weekend working at the Moores Creek National Battlefield 250th Event. The small National Park near Wilmington, NC had called on other rangers to assist, as parks often do for big events.

Continue reading “Embedded With The Troops at Moores Creek”Author: Bert Dunkerly

Canadian Invasion: The Occupation of Montreal

In the fall of 1775, 250 years ago, the American Revolutionaries invaded Canada. It was hoped that a 14th colony could be added to the effort. Members of the Continental Congress felt that Canada’s majority French Catholic population was unhappy with British rule, and would welcome the chance to join them. Conquering Canada would also remove the potential for a British invasion from the north.

General Richard Montgomery led forces from New York State north, and by November 13 captured Montreal. He and most of his troops departed for Quebec on November 28, where they joined forces with General Benedict Arnold to attack that city. General David Wooster remained in command at Montreal.

The Chateau Ramezay in the center of the town became headquarters for the occupying Continental Army. In the meantime American forces were defeated at Quebec on December 31, with General Montgomery killed.

By spring, Montreal was under the command of Colonel Moses Hazen, a resident of the Province of Quebec. He tried to raise troops for the Continental army, but only about 500 joined his Canadian Regiment.

With about 10,000 people, Montreal was the fifth largest city in North America. While residents initially welcomed the Americans, they soon saw them as invaders and occupiers. Uncertainty about the economy, American intentions, and the defeat at Quebec all caused Canadians to gradually lose support for the Americans. For the Continental troops stationed here that winter, it must have been a dreary, cold, and depressing experience.

View of Montreal and its Walls in 1760. Image Source: Pictorial Field-Book of the American Revolution by Benson Lossing (1860).

On April 29, 1776 a delegation from the Continental Congress arrived, which included Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Chase, Charles Carroll, and Carroll’s cousin, John Carroll, Catholic priest. It was hoped that a priest would give the American cause more legitimacy with the Canadians. Upon arriving, General Arnold had his troops salute the Congressional delegation.

Charles Carroll wrote, “On our landing, we were welcomed by General Arnold in the most courteous and friendly manner and conducted to the headquarters where a society of women and gentlemen of distinction had assembled. As we were on our way from our landing site to the General’s house, the cannon of the citadel thundered in our honour as commissioners of the Congress.”

It was all a failure. The Canadians were unwilling to throw off British rule, which guaranteed religious freedom and protection of their language and culture. On May 11, 1776, Franklin departed, saying it would have been easier if the Americans had tried to buy Canada than invade it.

Arnold and his troops occupied Montreal until June 15, when British forces advancing from Québec forced their evacuation. For seven months, the largest town in Canada was under American military occupation.

Today one of the few reminders of the American occupation is the Chateau Ramezay, built in 1705. It had been the Governor’s mansion during British rule and was the seat of Government until 1849. It is now a museum. Also visible are the old stone walls that surrounded the city. These fortifications defended the town in 1763 during the French and Indian War, and again in 1775 and 1776.

The End of the Great War

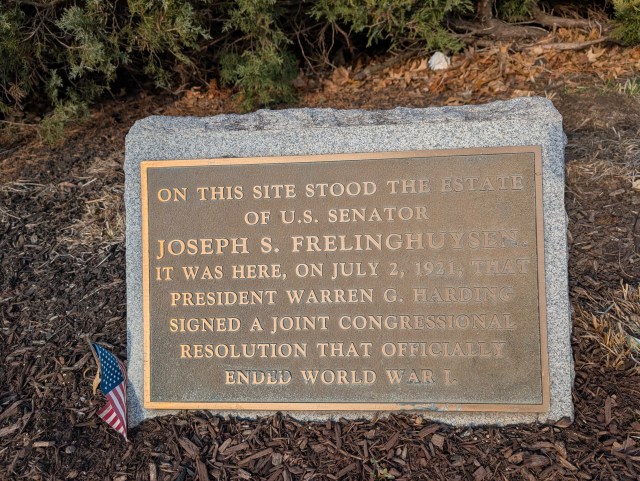

World War I ended in a Burger King parking lot in New Jersey. Really! Trust me. While visiting Revolutionary War sites in New Jersey, I had to chance to visit something I’d known about but not yet seen. I hope readers are ok this slight deviation from Revolutionary history.

World War I raged from 1914-1918, with the United States entering in 1917. The Allied nations consisted of the U.S., U.K., France, Italy, Russia, Serbia, and Japan. The Central Powers included Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire. By the fall of 1918 the other Central Powers had dropped out, leaving only Germany still fighting.

On November 11, 1918, Germany agreed to an armistice with the Allies, halting the fighting. Negotiations began on a final peace treaty, resulting in the Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919. But the U.S. did not sign it. Wilson, a Democrat, faced Republican opposition in Congress. Large portions of the American population also opposed the settlement. There was also opposition to Wilson’s proposed League of Nations, an organization similar to today’s United Nations.

So while the rest of the Allies settled with Germany in 1919, for two more years the U.S. and Germany were still at war, with the Armistice in place. President Wilson’s successor, Warren G. Harding, also opposed the Treaty of Versailles, so suggested that Congress make a separate peace treaty that did not include American membership in the League of Nations. Senator Philander Knox introduced such a resolution and it passed the Senate in April, 1921.

Representative Stephen G. Porter proposed a similar measure in the House. Both houses of Congress modified the two proposals, creating the Knox–Porter joint resolution and passing it on July 1. At the time President Hardig was visiting New Jersey Senator Joseph S. Frelinghuysen and were playing golf at the Raritan Valley Country Club.

The golf course was across the street was the Frelinghuysen estate. Word arrived that a courier was on his way from the Raritan train station, having traveled from Washington with the signing copy of the resolution. Harding walked back to the estate, signed the document, and then returned to complete his round of golf. The Frelinghuysen estate was destroyed by fire in the 1950s, and the site is now occupied by a shopping center and parking lot, with a small plaque marking the place where the home once stood.

Senator Joseph S. Frelinghuysen was the descendant of Frederick Frelinghuysen, who served as a Major General of militia during the Revolution. He was also in the Continental Congress and the Senate.

So while we think of World War I as ending on November 11, 1918, the actual peace treaty with Germany didn’t occur until three years later. Article 1 of the treaty required Germany to grant to the U.S. government all rights and privileges that were enjoyed by the other Allies that had ratified the Versailles treaty two years earlier. And today there’s a Burger King on the site in Somerville, New Jersey.

The Best 250th Logos

We write about serious topics all the time here, which we should. But sometimes its nice to have some fun. This one will be fun. One of the things that stands out to me as I read about upcoming events and programs going on across the nation are graphics and illustrations. Logos. There’s nothing like a great logo. It can capture the spirit of the team/place/group. One of my favorite logos is this one (I sure hope Rob Orrison is reading):

The Bicentennial produced what I think is a great, classy looking logo:

By comparison, the official 250 logo for the nation’s commission is bland and boring to me:

https://america250.org

As we’ve entered the 250th commemoration, I’ve noticed the various logos for state 250 commissions. Some I really like, some are o.k., and some are just plain . . . boring. I’ll run down my opinion on the various state 250th logos. There are many state commissions, so to keep this manageable I’ll just focus on those of the original thirteen states. And I’ll go through them in alphabetical order so as to avoid any sense of favoritism.

Connecticut

I’ll just say it: it’s boring. I love the Nutmeg State and it has some great historic sites. But the logo falls flat. Just the state name, with the ‘C’ in blue to set it off.

https://ct250.org

Delaware

Good work, First State. It’s short, sweet, colorful, patriotic, and I like the state outline.

https://delaware250.org

Georgia

It’s o.k. Good colors, but kind of bland to me.

https://exploregeorgia.org/ga250

Maryland

Not a fan. Neither exciting or interesting. Too many letters, not enough graphics.

https://mdtwofifty.maryland.gov

Massachusetts

It’s ok. The state abbreviation and ‘250’ look very 70s to me. I honestly expected more from a state with such rich Revolutionary history.

https://massachusetts250.org/healey-unveils-massachusetts-250-initiative-to-celebrate-anniversary-of-independence

New Hampshire

Come on, Granite State! New Hampshire currently has no state 250th Commission. Let’s hope the state addresses that soon.

New Jersey

The Garden State’s logo features an illustration representing the state’s role as the Crossroads of the Revolution. I’m not crazy about the colors, though.

https://www.revnj.org

New York

Definitely a winner. It has clear lettering, patriotic colors, and the image of the flag on the state outline.

https://www.nysm.nysed.gov/revolutionaryny250

North Carolina

Not crazy about it. Sorry, Tarheel State. The letters are too small and thin, and there are no graphics.

https://www.america250.nc.gov

Pennsylvania

The Keystone State has used its state abbreviation with the numbers ‘250.’ It reminds me of money. Simple, but it works. I do wish it had more to it, though.

https://www.america250pa.org

Rhode Island

Spot on. Nice logo, with the anchor, a symbol of the state, and abbreviation and ‘250.’ It’s easy to read, sharp, and captures the state’s history.

https://rhodeisland250.org

South Carolina

I think the Palmetto State could’ve done better. It’s not awful, but not inspiring either. The letters and wording could really use an image or graphic to go with them. How about a palmetto?

https://southcarolina250.co

Virginia

I like the use of red, white, and blue in the Old Domion’s logo, as well as the thick font for the letters and numbers. It’s a good one. I wish it was a bit more visual, with maybe a state outline or something, but overall, I like it.

https://va250.org

What do you think? What do you like best? Do you live in another state with a great logo? Share it.

This is not in any way meant to criticize any state’s commemorative efforts. Every state is doing great programming. Check out their websites and support their programs. And be sure to check out the national 250 website:

https://america250.org

Special Exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Army

The National Museum of the United States Army in northern Virginia is well worth a visit. Covering the history of the U.S. Army from colonial beginnings to current operations, it is one of the most impressive museums I’ve seen. Several large galleries focus on major periods of the army’s history, such as the Revolution, Civil War, World War I, World War II, Korea and Vietnam, the Cold War, and current conflicts.

Recently the museum opened a special exhibit on the establishment of the army and the Revolution: “Call To Arms: The Soldier and the Revolutionary War.” It is absolutely outstanding. The exhibit brings together rare items from the army’s collection as well as from museums across the country. The assembly of artifacts is amazing: a cannonball from Trenton, examples of every major type of rifle and musket, a Ferguson Rifle, the sword Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, several rare original uniforms, and pistols owned by George Washington.

Flags from the era are extremely rare, and here one can see four original Revolutionary War flags. One of the highlights is that of the Rhode Island Regiment, which has not been out of the state since the Revolution ended.

I’m normally not big on technology but the exhibit featured two well done battle map videos, one on Bunker Hill, the other on Yorktown. A looping video in one corner covered soldier life in camp and on the march, dispelling myths and going into detail about medical care, rations, and more.

For more information about the exhibit, and the museum itself, visit their website:

https://www.thenmusa.org/

Visiting Parker’s Revenge

During the recent ERW road trip to Massachusetts for the 250th events, I saw the newly marked Parker’s Revenge site at Minute Man National Historical Park. Some of our readers may know that recently the National Park Service conducted archaeology here and discovered the site of part of the April 19, 1775 battle. It was wonderful to see this site now marked and interpreted.

Captain John Parker commanded the Lexington militia who confronted the British early that morning. Suffering eight killed and ten wounded, they fled in confusion from the Lexington green. Regrouping later that morning, they joined in the counterattack on the British column as it moved back towards Boston, the site being named Parker’s Revenge.

Nathan Munroe, a veteran of the clash, remembered fifty years later, “About the middle of the forenoon Captain Parker having collected part of his company, I being with them, determined to meet the regulars on their retreat from Concord. We met the regulars in the bounds of Lincoln. We fired on them and continued so to do until they met their reinforcement in Lexington.”

While park staff had a general idea of where this occurred, recent archaeology confirmed the location. Not far from a section of the road, behind the Minute Man Visitor Center, there is a large rocky outcrop that for decades had been thought to be the site of this phase of the battle. Yet there was little evidence to support this theory.

A multi-year historical and archaeological investigation funded by the Friends of Minute Man National Park and the American Battlefield Trust, allowed archaeologists and volunteers to investigate the area. Finding musket balls and military artifacts, they could accurately determine troop positions.

The investigators searched the woods just north of the outcrop in the hopes of finding evidence of the British flankers, who moved ahead of and around the main body to protect it. Archaeologists found evidence of their position, as well as of the militia.

Today there is a maker identifying the site and discussing the recent archaeology. Another nearby provides an illustration to help envision the fighting here. These new markers are a good reminder that we are still learning and often do not have all the answers, even for a well preserved and well documented event like this.

The Militia Myth

In the aftermath of the April 19, 1775 fighting at Lexington, Concord, Menotomy, and the road back to Boston, militia swarmed from across New England to surround the British forces in Boston. With fighting now underway, a wave of enthusiasm swept through the region, with a decade of tension now broken by actual combat.

Continue reading “The Militia Myth”Virginia 250th Events

Momentum for the 250th Anniversary is really picking up steam, as seen with recent special events in Virginia. On Sunday, March 23, St. John’s Church in Richmond observed the 250th anniversary of Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech.

The church held three reenactments of the meeting of the Second Virginia Convention, each sold out. In attendance at the 1:30 showing (thought to be about the time of the actual meeting), were filmmaker Ken Burns and Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin. Outside the church, reenactors greeted visitors, and representatives from several area historic sites had displays, including Mount Vernon, Wilton House Museum, Red Hill, the VA 250 Commission, Richmond National Battlefield Park, Tuckahoe Plantation, and the Virginia Museum of History and Culture. Mark Maloy, Rob Orrison, Mark Wilcox, and Bert Dunkerly of ERW were all present.

That afternoon park rangers from Richmond National Battlefield Park gave a special walking tour through the neighborhood focused on Henry’s speech and the concepts of liberty and citizenship through time.

That evening Richmond’s historic Altria Theater hosted the very first public premiere of Ken Burns’ new documentary, The American Revolution. A sellout crowd of over 3,000 saw snippets of the video, along with a panel discussion with Burns and several historians. The documentary will air nationwide starting on November 15.

Then, Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, Colonial Williamsburg hosted a gathering focused on 250th planning called, A Common Cause To All. The event featured about 600 representatives from historic sites, museums, and state 250 commissions. In all forty states were represented. Attendees discussed event planning, promotion, upcoming exhibits, educational opportunities, and more.

In his speech on March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry noted that “the next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms.” True enough, just a few weeks after his speech, word arrived of the fighting at Lexington and Concord. And soon, our readers will hear about the special events commemorating this anniversary in Massachusetts.

National Park Service Historic Weapons Programs

Many of our readers love seeing the rifle and cannon demonstrations held in National Parks. Have you ever wondered about how park rangers manage this program? Recently I attended Historic Weapons Certification, an intense, two-week training held every few years for Park Rangers.

The program began in the 1970s with the coming of the nation’s Bicentennial, and has evolved over the years. Held at a National Guard base in Anniston, Alabama, the course teaches participants how to load and fire historic weapons, care and maintenance of equipment, historic manuals for loading and drill, storage and handling of black powder (a Class A Explosive), and Park Service policies for historic weapons programs. There are only about 152 certified Historic Weapons Supervisors in the entire National Park Service.

Continue reading “National Park Service Historic Weapons Programs”The Soldier by the Road

Growing up in central Pennsylvania, the history of the Revolution seemed far away. There were no major battles here, and the big armies did not pass through here. The area produced no famous leaders or generals.

Read more: The Soldier by the RoadMy hometown, Lewisburg, sits on the banks of the Susquehanna River. In the 1770s the area was the frontier, and Revolutionary connections here are few and far between. The militia served far away during the Brandywine and Germantown campaigns. There were some Indian raids through the region as well.

One thing I was always curious about, but never acted on, was the headstone of a Revolutionary soldier, literally next to Route 192. It is in the middle of nowhere, far from any towns or forts. I had moved away but on a recent visit I had the chance to pull over, look at the marker, research the name, and find out who the soldier by the road was.

Christian Hettick was born in 1750 in Rheinland-Pfalz, modern Germany. He moved to Pennsylvania and settled with many other Germans in the Susquehanna Valley. He resided along the Susquehanna River in what later became the town of Lewisburg. In 1781 he was serving with the Northumberland County militia (today the area is in Union County).

While the Yorktown campaign was underway 300 miles to the south, reports of hostile Indians brought the militia out to patrol here. Finding no hostile enemy, Christian was apparently returning home when he encountered Indians, who shot, killed, and scalped him.

His body was found by the side of the road. He left a pregnant widow, Agnes, with four children, and a daughter was born shortly after his death. His son seven-year-old son Andrew was actually with his father when he was killed. The Indians captured Andrew, but he escaped after several months.

So there he rests, literally by the side of a busy road (thankfully no cars have taken out the small marker). In this quiet corner of central Pennsylvania, far from the large battlefields and campsites, is this reminder of the Revolution.