Examples of women’s political participation in the Revolutionary movement are hard to find. Women were not permitted to be politically active in the eighteenth century, yet many got involved anyway and pushed back against prevailing social norms. There are two examples of women organizing protests within six months of each other in 1774, both in North Carolina. Unfortunately, few details exist of these happenings. Primary sources on many colonial-era events are limited, and they are even more so with these two examples.

By the early 1770s, tensions had been building for a decade between the North American colonists and British officials. Debate swirled around taxes, representation, and rights. Parliament affirmed their right to tax all citizens of the empire, while Americans insisted that only their locally elected representatives (colonial legislatures) could do so.

In 1773 the British government enacted the Tea Act, aimed at both assisting the struggling East India Tea Company, and undercutting smuggling on the part of the Americans. Tea was a drink for the upper and middling classes in the American colonies, most colonials never tasted it. Yet tea became symbolic in the growing debate that was dividing England and the colonies.

In each colony, leading men organized to protest what they saw as unfair taxes and unequal treatment. Their argument stemmed from the fact that they were not being treated as British subjects, independence was not yet on the minds of most. The majority of Americans hoped for reconciliation with the mother country and hoped to find a solution to the problems they faced. The Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773 crossed the line into new forms of protest: with mob violence and destruction of property. It was a result of pent-up anger and frustration. The Tea Party, in which protestors dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor, resulted in damages worth over one million dollars in modern currency. There were other tea party protests in other colonies, all smaller and less known today.

Sometime between March 25 and April 5, 1774 a group of women in Wilmington, North Carolina staged their own protest against the tea tax. They gathered in the port town and publicly burned tea. Unfortunately we do not know where, how much tea, whose it was, who organized it, or public reactions.

In fact there is only one account of this event, written by English-sympathizer Janet Shaw. She recorded, “The Ladies have burnt tea in a solemn procession, but they delayed however till the sacrifice was not very considerable, as I do not think any one offered above a quarter of a pound.” This one sentence by an unsympathetic observer is our only source for this event.

Wilmington Waterfront. Somewhere along the waterfront a group of Wilmington women burned tea in a public protest. Author photo.

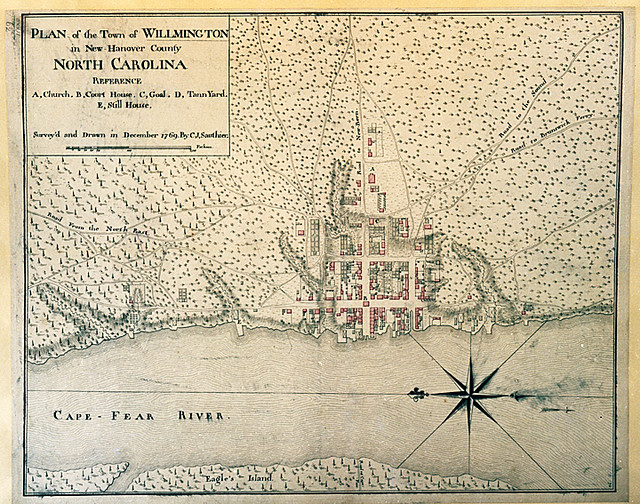

Wilmington was North Carolina’s largest town at the time, and an important port. Its economy was tied to shipping and trade: over half the colony’s exports passed through the Lower Cape Fear region. The town had about 150 homes and about 1,000 residents.

Sauthier map of Wilmington. Created in 1769, it shows how Wilmington looked on the eve of the Revolution. (North Carolina State Archives)

Burning tea in public was a very visible and no doubt shocking act. Yet we only have this one sentence by an observer, no other details about the event, and nothing of its planning or its aftermath. Perhaps it was some of the wives of leading merchants who organized this public protest. Wilmington had already been the scene of protests during the Stamp Act crisis nine years earlier. Were the region’s women influenced by those actions?

Just 200 miles to the north, Edenton was far removed from the major urban centers like Boston or Philadelphia, but was one of the important ports of North Carolina. The town had about fifty homes and was the county seat of Chowan County. Its leading men, lawyers, judges, and merchants, were united in supporting American rights.

On October 25, 1774 a group of women gathered to formally protest the tax on tea, and produced a document to that effect. Unfortunately facts about the event remain murky. There is uncertainty as to where the meeting took place, and who led it. One theory suggests that a small group met and circulated the petition for others to sign it. In all, 51 women signed their names to the document that read:

As we cannot be indifferent on any occasion that appears nearly to affect the peace and happiness of our country, and as it has been thought necessary, for the public good, to enter into several particular resolves by a meeting of Members deputed from the whole Province, it is a duty which we owe, not only to our near and dear connections who have concurred in them, but to ourselves who are essentially interested in their welfare, to do every thing as far as lies in our power to testify our sincere adherence to the same; and we do therefore accordingly subscribe this paper, as a witness of our fixed intention and solemn determination to do so.

Penelope Barker has traditionally been cited as the leader, but we are not sure. Barker wrote a letter to accompany the protest, and sent both to the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, a British newspaper, which published it on January 16, 1775.

Penelope Barker. (North Carolina Museum of History)

Penelope’s letter was even more forceful than the petition, stating:

The Provincial Deputies of North Carolina, having resolved not to drink any more tea, nor wear any more British cloth, many ladies of this province have determined to give memorable proof of their patriotism, and have accordingly entered into the following honourable and spirited association. I send it to you to shew your fair countrywomen, how zealously and faithfully, American ladies follow the laudable example of their husbands, and what opposition your matchless Ministers may expect to receive from a people thus firmly united against them.

Penelope’s husband Thomas was the colony’s treasurer, and was actually away in England at the time. Other women’s husbands were prominent leaders as well. Note that last line of Penelope’s letter to British officials: the Americans were “firmly united against them.” Such language would not even appear in the Declaration of Independence. Her letter also notes what the petition itself does not, that they will refrain from not only tea but British cloth and other goods.

The protest generated a satirical response from Britain, more for the women taking a foray into politics than for the message about American rights. A political cartoon satirized the women as ugly and neglecting their motherly and home making duties. One British writer referred to them derisively as Amazons and wrote in jest of a female Congress.

“A Society of Patriotic Ladies at Edenton in North Carolina” London : Printed for R. Sayer & J. Bennett, 1775 March 25. (Library of Congress)

There is little record of reaction in North Carolina itself or other colonies. Nor do we know what their husbands thought of their actions. Such an event would surely have been noteworthy.

Penelope Barker died in 1796 at age 68, and thankfully an image of her exists. What did she do during the war itself? What did the community think of her? What about those other fifty women? We don’t know.

It is impossible to know when the last participant of the Wilmington Tea Party died, but many likely lived into the 1800s, and could have been interviewed or photographed. But they were not. All of those women remain anonymous.

As is often the case, there is so much we don’t know, and we wish we knew more. Did the Wilmington Tea protest in fluence the one in Edenton? Or was it just coincidence?

What did the other ladies of Wilmington and Edenton do during the war that followed? Did they continue to be politically active? Did they discuss social changes as the state formed a new government in 1776 and later when the Constitution was debated in 1787? As is often the case, we have fragmentary evidence and only get a glimpse of their actions and attitudes.

nice article !

LikeLike

Thank you Kip!

LikeLike

The inclusion of Penelope Barker’s letter in this article was so interesting. It makes me wonder if the women knew that their actions would be seen as comical in Britain and possibly wanted to use forceful language to affirm their positions? Or maybe Penelope and the other women were just that fired up when she wrote it?

Thank you for writing this, I’ve enjoyed the snippets we get of women’s roles in the war.

LikeLike

Thank you, Abi. Good question, and of course we’ll likely never know. I’m sure they knew that their actions were out of line with the norms, and that in publicizing it they were inviting criticism. But maybe that was the point, it would draw attention to the issue.

LikeLike

Pingback: 250th Anniversary of the Boston Tea Party - James Monroe Museum and Memorial Library

Pingback: On this day 250 years ago in the Revolution — April 5, 1774 – On This Day In The Revolution

Awesome text for school

LikeLike

I love this article. I am trying to write an essay and this is giving me all the things I need for it.

LikeLike

Thank you! So glad you found it helpful! Thats why we do this!

LikeLike

very informational for an essay

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike