The American Revolution on the frontier produced its share of stories and legends. In many ways, the heroes in those tales were more relatable than the men who led the war east of the Appalachians. They were not land-owning generals like George Washington, political organizers like Sam Adams, world-renowned scientists like Benjamin Franklin, inspiring speakers like Patrick Henry, or political philosophers like Thomas Jefferson. Instead, they were farmers turned amateur soldiers, trappers and hunters turned scouts, family men turned avenging marauders. In at least one case, even a quasi-fugitive from the law could become a symbol of protection and security.

By the 19th century, names like Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton, Ebenezer Zane, Lewis Wetzel, Issac Shelby, and Samuel Brady were known to every schoolboy west of the Appalachians. Some of their reputations faded with time as the frontier moved west onto the Great Plains and into the Rocky Mountains. Still, the stories remained, mostly to sit in in aging volumes on a library bookshelf, but occasionally to be dusted off for works of historical fiction. Like most stories, they occasionally morphed and evolved over time in the retelling. Sometimes they hold up quite well on close examination and can be verified.

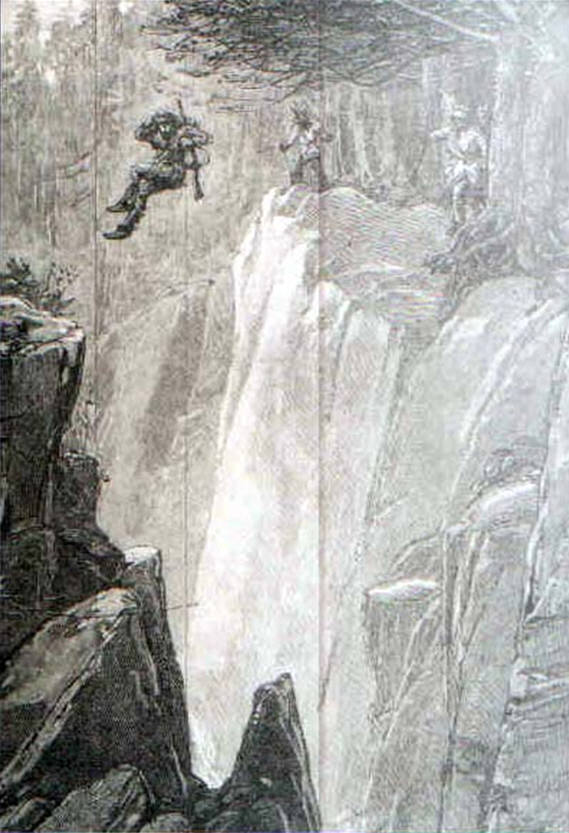

Sometimes a little more skepticism may be in order. Samuel Brady’s leap over a river is one such story. There are two versions of the story. In one he leaped to the opposite side of a rocky Cuyahoga River chasm. In the other, he leaped entirely across a deep ravine through which Slippery Rock Creek ran.

Samuel Brady enlisted as a rifleman in 1775, fighting in the east with his father and brother in several iterations of the First Pennsylvania. Eventually, he was promoted to captain and transferred to the 8thPennsylvania, which was posted at Fort Pitt. As popular histories in the 19th century told it, sometime in 1780 Brady took several men out to pursue a Native American raiding party that had attacked white settlers along the Monongahela River in Washington County, Pennsylvania. He suspected the raid of originating in the area around the falls of the Cuyahoga River (today’s appropriately named Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio). The region was reasonably well traveled as it was near a portage between the Cuyahoga River, which looked north toward Lake Erie, and the Muskingum River, which flowed south towards the Ohio River. (Naturally, the area later became Portage County, Ohio.) A few miles short of the Cuyahoga, Brady split his men into two groups, one headed north and a second headed westward toward the falls. Brady led the second group. It ran smack dab into the warriors it had been pursuing and promptly found itself outnumbered. After a brief exchange of shots, Brady ordered his men to retreat and scatter. The Native Americans, however, recognized Brady and focused their attention on capturing him.

The warriors herded Brady toward a narrow point on the Cuyahoga where it cut through a rocky gorge. The gap between the two sides at the top was narrow, perhaps twenty-two feet, but widened out at the bottom. In one popular version, “Brady, as he approached the chasm, concentrating his mighty powers, knowing that life or death was in the effort, leaped the pass at a bound. It so happened that a low place in the opposite cliff favored the leap, into which he dropped, and, grasping the bushes, helped himself to ascend the top of the precipice.”[1] On opposite sides, Brady and the Indians taunted one another and the Indians may have fired at him and wounded him. He evaded them until reaching a nearby marshy pond, which he waded into, crouched down, submerged himself, and then breathed through a reed until the Indian warriors gave up their search. Today, the presumed site of Brady’s leap is marked by a boulder in Brady’s Leap Park in Kent, Ohio and the marsh where he hid is known as “Brady’s Pond,” not too far away.[2] By the late 1800s, the story had been repeated so many times as to be taken for gospel. Except…

Other nineteenth century biographies relate a very similar story about Brady, but in those tales he leapt across Slippery Rock Creek, 70-80 miles to the east in western Pennsylvania. In this version, Brady and some of his men were scouting the area north of Pittsburgh along Slipper Rock Creek, again in 1780. They came across an Indian trail in the evening and pursued until dark, finally catching up with a raiding party early the next morning. At the same time, a second group of Native American warriors had come across Brady’s trail and he quickly found himself between two groups. When Brady and his men opened fire on the group they had been pursuing, they quickly found themselves fired upon from the group pursuing them. Caught between two groups, Brady ordered his men to retreat. The Indians, recognizing Brady as an inveterate enemy, focused on him. Similar to the Cuyahoga story, Brady approached Slippery Rock Creek at a point where it was “washed in its channel to a great depth.” Closely pursued by the Native American warriors: “Quick of eye, fearless of heart, and determined never to be a captive to the Indians, Brady comprehended their object and his only chance of escape, the moment he saw the creek; and by one mighty effort of courage and activity, defeated the wone and effected the other. He sprang across the abyss of waters, and stood, rifle in hand, on the opposite bank, in safety.”[3] Brady reportedly estimated the difference at 23 feet.

Other than their locations, the critical aspects of the Ohio and Pennsylvania stories are remarkably consistent and reasonable. Brady frequently led small parties employed in scouting missions like those described in both versions. Brady and his men ranged across an area of operations from the Sandusky River in western Ohio to most of western Pennsylvania, encompassing both the Cuyahoga River and Slippery Rock Creek valleys. Encounters with Native American raiding parties were common enough and often involved ambushes, pursuits, and retreats. At least twice, Brady rescued captives from Indian raiding parties. The captain was also known for his physical stamina, strength, size, and quick thinking, attributes that would lend themselves to leaping chasms, creeks, and streams without hesitation, particularly when trying to escape an enemy hellbent on killing him. (A third hand-account in 1856 related the story that Brady was captured by Indians in 1780 and escaped while being burned at the stake near Sandusky, was pursued across the modern state of Ohio before making his leap over the Cuyahoga at Kent, Ohio and then hiding in the lake subsequently named after him).[4]

There are a few hitches in the story, however. Published eighteenth century records contain ample references to Samuel Brady and contemporary descriptions of many of his missions and feats, certainly enough to build and sustain the legend, but nothing about him leaping the Cuyahoga River or Slippery Rock Creek. That story appears in the 19th century, as writers and historians crafted books about the 18th century frontier. Every now and then, however, a debate would pop up over the feasibility of making such a leap, usually over the Cuyahoga River. Eager detectives noted that in the late 1800s the site of the purported leap was much wider than 23 feet. The story’s defenders, however, would point out that the Cuyahoga River chasm had been widened for various reasons: historic erosion, canal-building, bridging activities, and the like. To be sure, leaping a narrow gorge would be a challenge, but the distances suggested are credible, particularly if Brady leaped from the top of one side and landed at the bottom of the other. When the Olympics movement conducted its first event in 1896, American Ellery Clark took home the gold with a leap just under 21 feet.[5] In 1991, Mike Powell set a record in Tokyo of nearly 30 feet.[6]

Instead, interviews with the captain’s younger brother, Hugh Brady—a historic figure in his own right who went on to become a general in the American Army—revealed that Hugh Brady never heard Samuel talk about it. Instead, Hugh Brady reported, “Brady’s Lake he named having discovered it as he went to Sanduskey, he never met an enemy there, as I have seen it stated, in some accounts of him. Brady’s leap is I apprehend a fiction, for I never heard him speak of it.”[7]

There is no way to know for sure whether Captain Samuel Brady leapt across a river, or a creek, in either Ohio or Pennsylvania to escape pursuing Native Americans. Even if we can’t confirm them, the main points of the story are plausible and were repeated enough to become an accepted part of Brady’s biography. One of the most cogent summations of the problem comes in a letter from L.V. Bierce, who forwarded a third-hand account of Brady to Judge John Bar in the mid-18th century: “The numerous traditions respecting ‘Brady’s Leap’ across the Cuyahoga River, and many other “hair’s breadth escapes” and adventures of that old frontiersman grow more and more vague and conflicting, with lapse of time. Even those which have been published at various times in the newspapers and elsewhere, do not agree with each other, nor with the most reliable oral tradition.”[8]

Nevertheless, Brady’s Leap certainly encapsulated the many feats in Brady’s frontier service that we can verify. At the end of the movie “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” a newspaper publisher interviewing Jimmy Stewart’s character decides preserving a legend may be more important than the facts behind a story, telling Jimmy Stewart: “This is the west, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

You can visit Brady’s Leap Park in Kent, Ohio (https://www.kentohio.gov/culture-community/kent-parks-and-recreation/parks/brady-s-leap-park/) and decide for yourself. Just don’t forget the gorge has been widened.

[1] Samuel Hildreth, Contributions to the Early History of the North-West, including the Moravian Missions in Ohio(Cincinnati: Poe & Hitchcock, 1864), 53-54. In 1954, the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County (IN) published a short monograph using this version of the story. The original was from the December 7, 1836 issue of Indiana Register. Staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County, Samuel Brady, Frontiersman (Fort Wayne: Boards of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County, 1954).

[2] https://www.kentohio.gov/culture-community/kent-parks-and-recreation/parks/brady-s-leap-park/

[3] Cecil B. Hartley, Life and Adventures of Lewis Wetzel, the Virginia Ranger; to which Are Added Biographical Sketches of General Simon Kenton, General Benjamin Logan, Captain Samuel Brady, Governor Isaac Shelby, and Other Heroes of the West(Philadelphia: G.G. Evans, 1859), 236. Sketches of the Life and Indian Adventures of Captain Samuel Brady (Lancaster, PA: S.H. Zahm & Co., printers) 1891, 23. Sketches is a collection of stories originally run as a serial in a small paper, The Blairsville Record, Blairsville, PA, which was published in 1858-1869, except for a break during the Civil War. Library of Congress, Directory of U.S. Newspapers in American Libraries. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn85025175/

[4] “Tradition of Brady, the Indian Hunter—Letter of General L.V. Bierce to Judge John Barr—Letter of Hon. F. Wadsworth to Seth Day, Esq.,” Western Reserve and Northern Ohio Historical Society, Tract Number 29, December 1875. Wadsworth moved to Pittsburgh in 1802 and heard the tale from a man named John Sumerall, a long-time resident. Wadsworth relayed what he thought Sumerall had conveyed to him in a letter to Seth Day in 1856. Brady died in 1796, indicating Sumerall was repeating local tradition and did not hear the story from Brady himself.

[5] “Long Jump at the Olympics,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_jump_at_the_Olympics. Accessed April 4, 2025.

[6] “Men’s Long Jump World Record Progression,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Men’s_long_jump_world_record_progression Accessed April 4, 2025.

[7] Louise Phelps Kellogg, ed., Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 1779-1781, Collections, Volume XXIV, Draper Series, Volume V (Madison, WI: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1917), 204.

[8] “Tradition of Brady, the Indian Hunter—Letter of General L.V. Bierce to Judge John Barr—Letter of Hon. F. Wadsworth to Seth Day, Esq.,” Tract Number 29, 2.