Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Eric Wiser

On August 4, 1735 printer John Peter Zenger was acquitted of seditious libel in a dramatic trial before a crowded courtroom in New York’s City Hall. Zenger languished nine months in jail before his acquittal for “printing and publishing a false, scandalous and seditious libel, in which His Excellency the Governor of this Province, who is the King’s immediate representative…” Zenger’s odds were long given New York Supreme Court’s disbarment of his original attorneys in the pre-trial stage. Aggrieved Royal Gov. William Cosby had a legitimate claim under English Common Law that he was seditiously libeled.[1]

Zenger’s fame as an early martyr of freedom of the press is well known. In terms of America’s founding, it’s difficult to imagine independence without the dissemination of ideas through pamphlets and newspapers. Benjamin Franklin, a printer himself whose own brother James was imprisoned by authorities in Massachusetts a decade before Zenger, commented on freedom of the press: “This sacred Privilege is so essential to free Governments, that the Security of Property, and the Freedom of Speech always go together; and in those wretched Countries where a Man cannot call his Tongue his own, he can scarce call any Thing else his own.”[2]

Despite being thirty-years before the Stamp Act of 1765, the Zenger trial and political conditions surrounding it have seedlings sprouting growth in the Revolution. The substance of these can be traced to the colonial grievances inspired by acts of Parliament which in turn became articulated in the Declaration of Independence. Factionalism between supporters of Crown representatives and those opposed was present in the Zenger episode in nascent form. The rhetoric expressed by Zenger’s attorneys is indistinguishable from the much of the lofty language in the Revolution less “independence.”

Gouverneur Morris, the author of the Preamble to the Constitution, and grandson of principal player in the Zenger drama, Lewis Morris was to have said, “the trial of Zenger established the germ of freedom, the morning star of liberty which subsequently revolutionized America.”[3]

Possessing a unique foreign perspective on Zenger’s trial, Antoine-François Prost Royer, Lieutenant-General of the Lyon Police, in January 1783 wrote his friend Benjamin Franklin while discussing a legal compendium he was editing: You will see at once the trial of Zenger, a bookseller of New York, so well defended by your compatriot [Andrew] Hamilton…all the more interesting because it contains one of the seeds of the present revolution and of American independence.”[4]

John Peter Zenger was unlikely to become “a useful symbol of the development of political freedom in America.”[5] As a young teen, Zenger arrived at the Palatine German refugee intake center at New York Harbor’s Nutton Island in 1710.[6] Zenger fled “a country where oppression, tyranny and arbitrary power had ruined almost all the people…”[7] Zenger’s father died enroute to New York, and his widowed mother secured for her son a printer’s apprenticeship to William Bradford under a program for Palatine children administered by Royal Governor Robert Hunter. William Bradford was the only printer in the colony of New York.[8]

Bradford and Zenger had a short partnership in 1725 before the latter started his own New York City print shop on Smith Street in 1726 and thus became the colony’s second independent printer. Zenger moved again in May 1734 to Broad Street. Zenger produced Dutch religious books while his former master and partner Bradford held the coveted rights to publish the colony’s legislative minutes and printed a newspaper, The New-York Gazette. [9]

Zenger’s career coincided with an intensely factional political scene. New York’s exponential commercial growth in the early-18th century-built fortunes that created conflicting interests among the ambitious of the colony. Competing interests fought for control of municipal offices and the legislative Assembly. Office holders squabbled for economic gain in attempting to guide fiscal policy such as duties, land grants, and interest rates. The two principal factions which were fluid “ideological chameleons” are known to history as “Morrisites” and “Philipses.”[10]

The Morrisite or ‘country’ faction that threw Zenger into fame, was generally provincial and less cosmopolitan than their opponents.[11] The bloc was named after Lewis Morris of Morrisania, an ambitious “man of letters” with a strong elitist streak who at the time of the Zenger controversy, was a member of the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court, a member of the Assembly, and President of the New Jersey Provincial Council.[12]

Morris’ strongest ally was Scottish-born attorney James Alexander. Alexander held numerous political offices in both New York and New Jersey, and was the father of Continental Army general William ‘Lord Stirling’ Alexander. Alexander’s Whig proclivities were fiery and he was the intellectual force behind Zenger’s newspaper.[13]

The opposition faction dominated by shipping and mercantilist interests was led by colonial-Dutch aristocracy product Adolphus Philipse. The Philipses or ‘Court’ party was “dependent on wealthy merchants, major landowners, and leading Anglicans.” [14]

In 1731, William Cosby succeeded John Montgomerie as governor of New York and New Jersey upon the latter’s passing. Cosby was a military officer from a distinguished family of English transplants to Ireland. Cosby had the requisite connections to help his military career and to later assist him in securing important imperial posts. Cosby was relieved of his governorship in the Balearic Islands under controversy and appointed governor of New York.[15]

Cosby and Morris clashed after the former arrived at New York City. At issue was the salary and perquisites paid to acting Gov. Rip Van Dam which Cosby believed he was entitled via a Royal decree he carried. Morris may have been protecting his own purse owing to his position as acting governor of nearby New Jersey and therefore moved to deny Cosby. New York and New Jersey were both governed by the same chief executive until Morris became the first separate governor of New Jersey in 1738.[16]

The public theater of Zenger’s controversy was the New York Supreme Court which met at City Hall on the site of present-day Federal Hall. Established three decades after England’s conquest of New Netherland in 1664, it was established by statute of the Assembly in 1691 and had original jurisdiction to hear both civil and criminal cases. The 1691 statute also refined English law in the colony by creating Justices of the Peace, County Courts (Sessions), and lower Common Law Courts. The legislature which established rules for the highest court, required all “matters of fact,” be decided by a jury of twelve local freemen.[17]

The three-member high court with Morris as Chief Justice held a session to listen to the views of attorneys representing Cosby and Van Dam regarding the holding of a Court of Equity as the solution. Cosby filed a lawsuit to utilize the Supreme Court as a Court of Equity because he couldn’t hold a Court of Chancery in which he would serve as Chancellor over his own litigation. Courts of Equity like Common Law courts in America, derived from England and provided remedies not available under Common Law. Courts of Equity, however, were juryless, which provided Cosby with a means to avoid a decision by local freemen.[18] The collection of the King’s overdue quit rents was Cosby’s reassurance to the Lords of Trade to further bolster the validity of his efforts.

Morris read a pre-prepared dissenting opinion as to the illegitimacy of Courts of Equity and in Cosby’s words, the Chief Justice “who by his oath and office was obliged to maintain the King’s prerogative, argued strenuously against it in the face of a numerous audience, teaching the people irreverence and disrespect to the best of Kings, and to his Courts of Justice.” [19]

Morris infuriated Cosby by publishing a substantively “polemical” opinion for public consumption. Morris argued that the King by his letters of patent, could not erect a Court of Equity without an act of Parliament – Cosby as the sovereign’s representative in America carrying Royal seals, therefore could not.[20]

Morris, though self-serving, sounded like a Whig of the Revolutionary generation by identifying ultimate sovereignty in the people through the colonial legislature. “And it being as clear as the Sun at Noon Day, that the King himself cannot by His Letters Patent (I still say according to the Laws of England) erect such a Court and establish Fees without Parliament; it necessarily follows that He cannot give such a Power to another… You are to recommend it to the Assembly of Our said Province, that a Law be passed…”[21]

Morris cited Lord Coke that by statute, a Court of Equity could not be established without an act of Parliament (i.e., the representative legislature). Local democracy in the form of the Assembly had rejected Courts of Equity in several resolves.[22]

Cosby dismissed Morris from the Supreme Court and elevated 2nd Justice and Philipse partisan James DeLancey, to Chief Justice.[23] This was a significant event in the New York political scene – the Chief Justiceship was likened to “having the power of a Pope.”[24]

Cosby penned the Duke of Newcastle that Morris’ removal would help depress disobedience to the Crown. “I am sorry to inform your Grace that the example of the Boston people begin to spread amongst these colonies in a most prodigious matter. I had more trouble to manage these people than I could have imagined.” Boston, the birthplace of the American Revolution, with its troublesome puritans had instigated rebellion against the Dominion of New England and its governor in 1689.[25]

Morris and his allies were determined to force Cosby from the governorship. Indeed, Morris, whose faction was out of power, sought to harness popular resentment of New Yorkers against Cosby and his allies. Petitions were sent to London, and Morris traveled there in late 1734 to press his case for readmittance to the Supreme Court and to have Cosby dismissed. An escalation in the New York’s information war was part of the Morrisite calculus in applying pressure.[26]

In the view of the Morrisites, William Bradford’s New -York Gazette was disposed to be friendly to the Governor. James Alexander believed the paper was being fed pro-Cosby propaganda which he called “ridiculous flatteries.” Alexander claimed that Zenger’s next project was “designed to be Continued Weekly, & Chiefly to Expose him [Cosby] . . .”[27]

John Peter Zenger’s newspaper, The New-York Weekly Journal launched in November 1733. Zenger printed The Journal; however, it was the editorial handy work of James Alexander who later wrote a bestselling account of Zenger’s trial.[28]

The Journal as “America’s first party newspaper” confronted and ridiculed Governor Cosby and his allies. Bernard Bailyn considered Zenger’s newspaper an important contribution of “opposition literature…which would issue the specific arguments of the American Revolution…” Not only did The Journal presage American’s critiques of Crown authority and British policy in general by opposing Cosby, but in printing Cato’s Letters by influential Whigs John Trenchard and William Gordon, the paper contributed to the dissemination of ideas such as natural law and the social contract. [29]

One issue of The Journal reprinted from Cato’s Letters words indistinguishable from the intellectual rhetoricians of the Revolution: “And Tyranny is an unlimited Restraint upon natural Liberty, by the Will of one or a few, Magistracy, among a free People, is an Exercise of Power for the sake of the People; and Tyrants abuse the People for the sake of Power.”[30]

The Journal compared Cosby to a petty tyrant and his administration’s competence called out. New York’s economy under Cosby, was deemed to be in a state of “deadness of trade.” The author of the piece blamed the recession on the governor and his handling of commerce which was detrimental to the pocketbook of the common man: “the baker, the brewer, the smith, the carpenter, the shipwright, the boatman, the farmer, the shopkeeper, etc.”

The Journal questioned Cosby’s competence in overseeing the colony’s defense in relation to the French. Two issues printed the “Middletown Papers,” accused Cosby of tyranny in his use of proroguing and dismissing the Assembly. [31] Outrage over British influence on colonial legislatures’ ability to conduct government business reached critical mass in the Revolution when proroguing and dismissing increasingly turned to dissolving. The Massachusetts Governing Act of 1774 was invoked by Massachusetts Gov. Thomas Gage to dissolve the Assembly. According to Prime Minister Lord North, the Act was intended to “take the executive power from the hands of the democratic part of the government.”[32]

The Declaration of Independence touched upon abuse of colonial assemblies and harangued the King “For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever,” and “He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.”

Cosby lost patience with The Journal sufficiently to shutter the newspaper. On January 15, 1734, Chief Justice DeLancey convened a Grand Jury of nineteen freeholders that failed to indict the editors of the paper with seditious libel.

Seven months later on October 15, 1734, Justice DeLancey held another Grand Jury in response to a satirical broadside published by Zenger. The municipal elections of New York City had been a superb success for the Morrisites and they wanted to maximize political capital. The broadside contained two “scandalous” songs celebrating the Morrisite cause and mocking Cosby on Courts of Equity.

The second Grand Jury failed again and Zenger became an easy target. On October 17, the Legislative Council resolved to go after Zenger. The Assembly and Court of Quarter Sessions refused to cooperate.[33]

On November 2, 1734 with Governor Cosby present, the Legislative Council condemned four issues of The Journal that “have a direct tendency to raise seditions and tumult among the people of this province…,” and that they be burnt by the hands of the Comon Hangman or whipper near the pillory in this City on Wednesday the 6th instant…that the Sheriff be ordered to See it effectually done and that the Mayor & other Magistrates of this City attend at the burning thereof.” They resolved that Zenger be arrested and jailed, and a reward given to anyone who discovered the authors.[34]

City Alderman appeared in agreement that the Council’s resolves in having bypassed the Assembly and Grand Juries were “opening a Door for arbitrary Commands….” One Alderman protested that the legal system ordering the Sherrif to conduct its dictates was duty bound to protect “The Liberty of the Press, and The People of the Province.” [35]

Zenger was arrested on Sunday, November 17, 1734, and placed in solitary confinement “denied the use of pen, ink and paper, and the liberty of speech with any persons.” Alexander, who had tightened the Gordian knot for Cosby by having Zenger print pieces supporting freedom of the press, subsequently argued for the printer’s release on a reasonable bail. DeLancey set the most excessive bail documented in New York on Zenger – his Morrisite benefactors chose not to pay the sum. Perhaps they were avoiding outing themselves, or more likely, Morris and Alexander wanted to martyr Zenger for their cause and use a jury trial to highlight Cosby’s tyranny. Bradford’s Gazette subsequently mocked Zenger’s abandonment.

With Zenger in jail, a third Grand Jury failed to indict him despite great lengths by a “tractable” Sherrif to find jurors friendly to the governor. The Attorney General contorted his prosecution to bypass a Grand Jury indictment by filing an “information” on January 28, 1735, on charges of seditious libel which circumvented democratic jury procedures. “In an admittedly political trial, this procedure doubtless alienated many otherwise neutral New Yorkers, and made the prosecution look even more unpopular.”

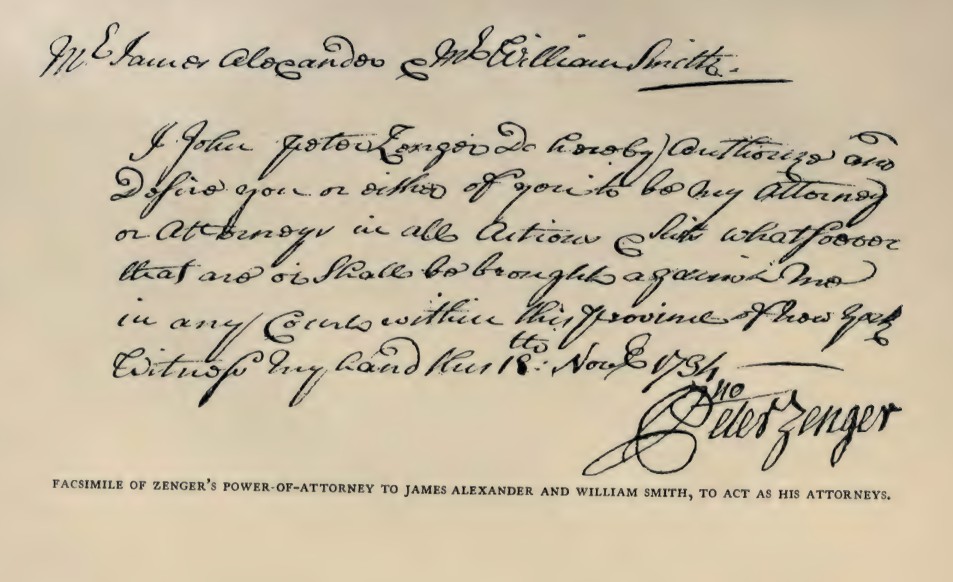

Zenger was officially charged for “being a seditious person and a frequent printer and publisher of false news and seditious libels, and wickedly and maliciously devising the government of our said lord the King of this His Majesty’s Province of New York.” English Common Law held that speech disturbing the concord between the King and his subjects was seditious libel. Zenger’s attorneys, Alexander and his partner William Smith came to Zenger’s aid and decided to make the latter’s courtroom defense an indictment on Cosby.

In a blow to Zenger, Alexander and Smith were disbarred in the pre-trial stage for challenging the objectivity of the Justices. Delancey’s punitive action has been interpreted as a “highhanded” means to deprive Zenger of capable counsel given the colony’s shortage of lawyers. DeLancey told the pair that their appeal was for a “great deal of applause and popularity by opposing this Court, as you did the Court of Exchequer [i.e. Equity]; but you have brought it to that point that either we must go from the bench, or you from the bar…”

Two days after Alexander and Smith’s disbarment, on April 18, 1735, court appointed attorney John Chambers entered a plea of “not guilty” on behalf of Zenger, and successfully petitioned the court for a struck jury. It wasn’t until the court’s next session in August that Zenger had his trial.

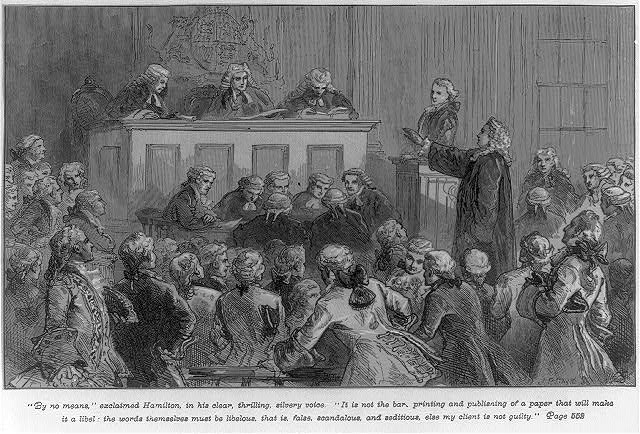

On August 4, 1735, the day of trial in crowded City Hall, an attempt to rig the struck jury against Zenger by switching the roster of jurors was discovered and ameliorated by Chambers. Zenger’s ultimate delivery came from accomplished Philadelphia attorney Andrew Hamilton who arrived at the request of Alexander. [36]

Hamilton’s challenge was to convince the jurors that Zenger of printing The Journal. Hamilton admitted that Zenger published the offending materials, which if the jury ruled him “guilty” on that admission, would have met DeLancey’s instructions that the jury rule only in “matters of fact.” Hamilton argued that Zenger was innocent due to the truth in The Journal of Cosby’s maladministration, “You will have something more to do before you make my client a libeler; for the words themselves must be libelous, that is, false, scandalous, and seditious or else we are not guilty.” The prosecution countered with the Star Chamber’s 1606 De Libellis Famosis ruling that the truer the words, the worse the libel, which Hamilton said was outmoded.

Hamilton asked the jury to rule as a “matter of law,” whereas Zenger’s council believed the jury had a right to use truth as a condition of acquittal for seditious libel via the outcome of the famous 1688 case of the Seven Bishops. The jury was protected in ruling as a “matter of law” Hamilton argued due to precedent set in the Bushel’s Case of Pennsylvania in 1670.[37]

Hamilton articulated to the jury, an essence that would later be in the ether in 1776: “…“And has it no often been seen (and I hope it will always be seen) that when representatives of a free people are by just representations or remonstrances made sensible of the sufferings of their fellow subjects by the abuse of power in the hands of a governor, they have declared (and loudly too) that they were not obliged by any law to support a governor who goes about to destroy a province or colony, or their privileges, which by His Majesty he was appointed, and by the law he is bound to protect and encourage.”

Hamilton, in words Samuel Adams could have used, argued that a free press was needed to hold a government accountable: “I will go farther, it is a right which all freeman claim, and ware entitled to complain when they are hurt; they have a right publicly to remonstrate the abuses of power in the strongest terms, to put their neighbors upon their guard against the craft or open violence of men in authority, and to assert with courage the sense they have of the blessings of liberty.”

The jury after a one-day trial and brief deliberation returned a verdict of “not guilty,” followed by “huzzahs” in City Hall. Zenger was released after nine months in prison the next day. [38]

A jury was considered by the Founding Fathers to be an essential heritage from England. The Morrisite defense of juries rhymes with the importance afforded them by the Revolutionary generation. Cosby reached for a Court of Equity in order to avoid a local jury in his suit vs. Van Dam. Zenger’s acquittal by his neighbors against a perceived abusive Royal official aligns with the colonists later contention that the Crown and Parliament, in manipulating who and where trials were judged, represented abject tyranny. Cosby’s refusal to accept Grand Jury outcomes, and Zenger’s acquittal, represents an early vindication of the check and balance the Patriot’s believed juries were against Crown officials.

Violators of the 1765 Stamp Act were to be tried in juryless Admiralty Courts. The Vice Admiralty Court Act of 1768 prescribed smuggling crimes to the Admiralty Courts, but went further in perceived aggressiveness by establishing them in Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. In 1774, the Administration of Justice Act provided a circumvention of local juries in cases involving Royal officials accused of capital crimes by allowing trials to be moved to other colonies or England.[39]

The Stamp Act Congress of 1765 resolved, “That trial by jury is the inherent and invaluable right of every British subject in these colonies.” The Declaration of Independence disparaged King George III “For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury.” [40]

Hamilton was remembered by Founding Fathers in later years. John Jay discussed the memory of Hamilton with Benjamin Franklin: “Dr. Franklin says he was very well and long acquainted With Andw. Hamilton the Lawyer who distinguished himself on Zengers Tryal at New York.”[41]

Zenger’s acquittal was discussed and reported on both sides of the Atlantic. Zenger published Alexander’s account of the trial which became a best seller reprinted in America and England throughout the 18th century.[42] Franklin’s print shop sold copies of the book and his Pennsylvania Gazette analyzed Hamilton’s defense which characterized it as a “popular cause,” in defense of “The LIBERTY OF THE PRESS.”[43]

Governor Cosby passed away from natural causes just months after the trial in 1736.

The decision changed nothing in terms of law in New York or the colonies in general. However, the precedent of acquittal by a colonial jury discouraged further prosecution of printers. In point of fact, it was only an incremental step toward free speech that advanced independence and home rule via the Assemblies as the arbiters. “Still, progress had been made, for it is one thing to be prosecuted and judged by one’s elected representatives and quite another to be assailed by the surrogates of the Crown.” [44]

[1] James Alexander, A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, Printer of the New York Weekly Journal, ed. Stanley Nider Katz (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 53-55, 58).

[2] “Silence Dogood, No. 8, 9 July 1722,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-01-02-0015.

[3] Livingston Rutherford, Family Records and Events: Compiled Principally from the Original Manuscripts in the Rutherford Collection (New York: DeVinne Press, 1894), 16.

[4] “To Benjamin Franklin from Antoine-François Prost de Royer, 7 January 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-38-02-0425

[5] James Alexander, A Brief Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, Printer of the New York Weekly Journal, ed. Stanley Nider Katz (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), Introduction 34.

[6] Second Immigration of the Palatines, June 13, 1710, in The Documentary History of the State of New-York. Vol. 3, ed. E.B. O’Callaghan (Albany: Weed, Parson, and Company, 1850), 333, 340 (DHSNY).

[7] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, 147.

[8] Names of the Palatine Children Apprenticed by Gov. Hunter 1710-1714, DHSNY 3: 340-341.

[9] Livingston Rutherford, John Peter Zenger: His Press, His Trial and a Bibliography of Zenger Imprints. Also a Reprint of the First Edition of His Trial, (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1914), 25-27.

[10] Michael Kammen, Colonial New York: A History, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 161-163, 203-206.

[11] Ibid., 203.

[12] Eugene R. Sheridan, Lewis Morris, 1671-1746: A Study in Early American Politics (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1981), 15-16, 203.

[13] Alan Valentine, Lord Stirling: Colonial Gentleman and General in Washington’s Army (New York: Oxford University Press, 1969), 6-11, 19.

[14] Kammen, Colonial New York, 205-206.

[15] Vincent Buranelli, “Governor Cosby and His Enemies,” New York History, 37, no. 4 (October 1956): 366-367, https://www.jstor.org/stable/244709800

[16] Ibid., Governor Cosby, 369-370.

[17] Deborah A. Rosen, “The Supreme Court of Judicature of Colonial New York: Civil Practice in Transition, 1691-1760.” Law and History Review 5, no. 1 (Spring 1987). 214-216, https://www.jstor.org/stable/743941

[18] Buranelli, Governor Cosby, 369

[19] Governor Cosby to the Lords of Trade, June 19, 1734. in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York. Vol. 6, ed. E.B. O’Callaghan (Albany: Weed, Parson, and Company, 1855), 4-7 (DRCNY).

[20] Sheridan, Morris, 150-151.

[21] Lewis Morris, The opinion and argument of the chief justice of the province of New-York concerning the jurisdiction of the Supream Court of the said province, to determine causes in a course of equity, (New York: John Peter Zenger, 1733; Ann Arbor: Evans Early American Imprint Collection), 5.

[22] Joseph H. Smith and Leo Hershkowitz, “Courts of Equity in the Province of New York: The Cosby Controversy, 1732-1736.” The American Journal of Legal History 16, no, 1 (Jan 1972). 23-24, https://www.jstor.org/stable/844810

[23] Buranelli, Governor Cosby, 371.

[24] Rosen, The Supreme Court of Judicature, 238.

[25] Buranelli, Governor Cosby, 368.

[26] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, Intro 7.

[27] Letter from James Alexander to Robert Hunter, November 8, 1733, in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of New Jersey. Vol. 5, ed. William A. Whitehead (Newark: Daily Advertiser Printing House, 1882), 360.

[28] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, Intro 8,

[29] Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), 43-45.

[30] New-York Weekly Journal. [No. 96 (September 8, 1735)] Available through Adam Matthew; Marlborough, American History, 1493-1945.

[31] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, Appendix A 117-119, 126-129, 137.

[32] Don Cook, How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760-1785 (New York: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1995), 187-188.

[33] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, Introduction, 17-18, Appendix A 109-110

[34]At a Council Held at Fort George in New York, the 2nd Nov, 1734, in Journal of the Legislative Council of the Colony of New-York, the 2nd Nov, 1734, Began the 9th Day of April, 1691; and Ended the 27 of September 1743, ed. E.B. O’Callaghan (Albany: Weed, Parson, and Company, 1861), 642 (JLCNY).

[35] Rutherford, John Peter Zenger, 42-44.

[36] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, Introduction 18-20, Trial 53-57.

[37] Ibid., Introduction 23, Trial 62, 78, 84-85, 91-92.

[38] Ibid., Trial 80-81, 101.

[39] Cook, How England Lost, 64, 188.

[40] Rosen, The Supreme Court of Judicature, 238

[41] “John Jay’s Notes on Conversations with Benjamin Franklin, 19 July 1783–17 April 1784,”, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-03-02-0165.

[42] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, Introduction 26, 36-37.

[43] The Pennsylvania Gazette [No. 469 (December 1, 1737)] Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/39396643; Benjamin Franklin’s Shop Book, 1737-1739, American Philosophical Society, https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/text%3A266513

[44] Alexander, A Brief Narrative, Introduction 29-30.

You have a good blog, but you are ignoring the work of my blog AmericanSystemNow.com. On the Zenger issue, people should see https://americansystemnow.com/freedom-of-the-press-an-american-hallmark/. Please get in touch about my contributing. Nancy Spannaus 703-772-0138

LikeLike