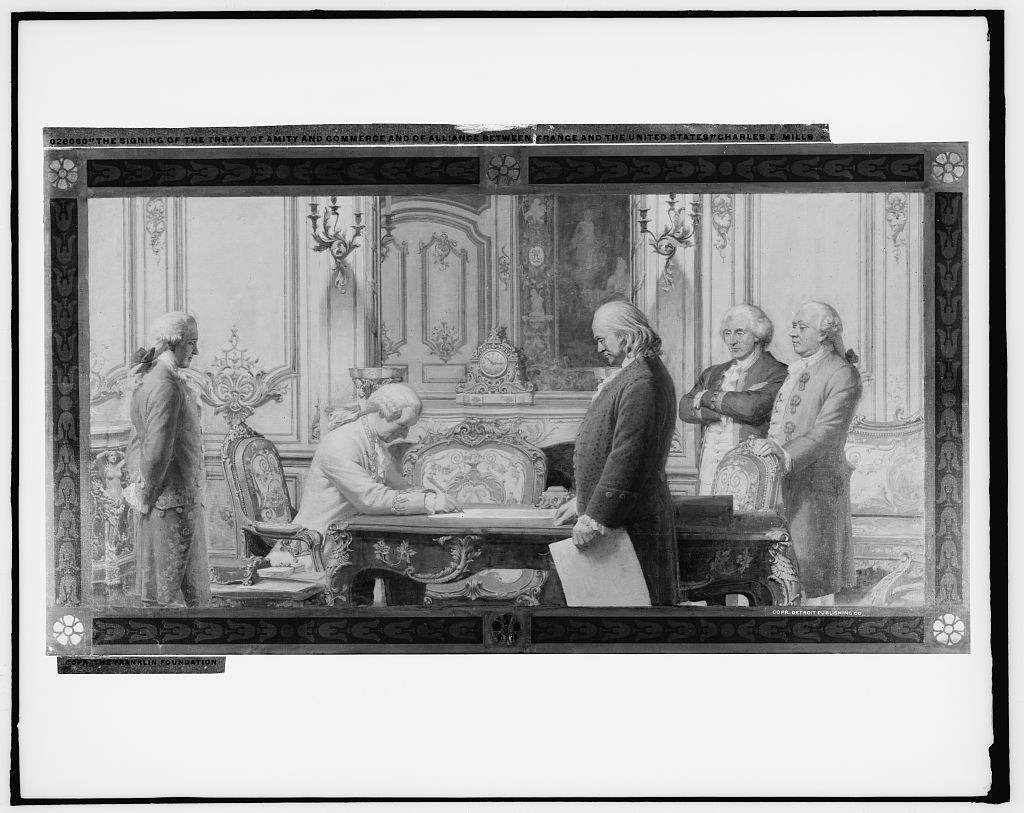

On this date in 1778, the fledgling American states officially found their great ally in France. The signings of the Treaty of Alliance and Treaty of Amity and Commerce gave new life to the cause of independence from Britain as Louis XVI pledged his support to the Americans.

An economic and military alliance with Britain’s age-old adversary had been long in the making. Early in the conflict, the French were hesitant to openly support the rebellion, instead opting to provide covert aid in the form of ammunition, weapons, and clothing. Following the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Silas Deane of Connecticut, and Arthur Lee of Virginia, were dispatched overseas to Versailles to engage in diplomatic talks with the French foreign minister, Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes. The success of these discussions would hinge on the battlefield performances of the American armies.

The following year was full of ups and downs for the Northern Army and Main Army. Although George Washington, commanding the latter force, had lost yet another major city when Philadelphia fell to the British in September 1777, his earlier victories at Trenton and Princeton had already impressed those on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, in October, an audacious offensive by Washington against the British at Germantown, though ultimately a defeat, demonstrated promise to the French that the Americans could sustain the conflict. In the end, however, it was the Northern Army’s victory over General John Burgoyne at Saratoga and the subsequent surrender of over 6,000 British and German soldiers on October 17 that secured the alliance.

When news arrived of the American triumph at Saratoga, Vergennes worked feverishly to persuade King Louis XVI that the time had come to openly support the fight against Britain. On February 6, 1778, the Treaties of Alliance and of Amity and Commerce were officially signed. At its conclusion, Deane and Franklin hastily penned a letter to President Henry Laurens of the Continental Congress to inform the governing body of the world-changing news:

Passy, near Paris, Feby. 8th. 1778.

Honourable Sir,

We have now the great Satisfaction of acquainting you and the Congress, that the Treaties with France are at length compleated and signed. The first is a Treaty of Amity and Commerce, much on the Plan of that projected in Congress; the other is a Treaty of Alliance, in which it is stipulated that in Case England declares War against France, or occasions War by attempts to hinder her Commerce with us, we should then make common Cause of it, and join our Forces and Councils, &c. &c. The great Aim of this Treaty is declared to be, to “establish the Liberty, Sovereignty, and Independency absolute and unlimited of the United States as well in Matters of Government as Commerce.” And this is guaranteed to us by France together with all the Countries we possess, or shall possess at the Conclusion of the War; In return for which the States guarantee to France all its Possessions in America. We do not now add more particulars, as you will soon have the whole by a safer Conveyance; a Frigate being appointed to carry our Dispatches. We only observe to you and with Pleasure; that we have found throughout this Business the greatest Cordiality in this Court; and that no Advantage has been taken or attempted to be taken of our present Difficulties, to obtain hard Terms from us; but such has been the King’s Magnanimity and Goodness, that he has proposed none which we might not readily have agreed to in a State of full Prosperity and established Power. The Principle laid down as the Basis of the Treaty being as declared in the Preamble “the most perfect Equality and Reciprocity,” the Privileges in Trade &c. are mutual and none are given to France, but what we are at Liberty to grant to any other Nation. On the whole we have abundant Reason to be satisfied with the Good Will of this Court and the Nation in general, which we therefore hope will be cultivated by the Congress, by every means that may establish the Union, and render it permanent. Spain being slow, there is a separate and secret Clause by which she is to be received into the Alliance upon Requisition; and there is no doubt of the Event. When we mention the Good Will of this Nation to our Cause we may add that of all Europe, which having been offended by the Pride and Insolence of Britain, wishes to see its Power diminished. And all who have received Injuries from her are by one of the Articles to be invited into our Alliance. With our hearty Congratulations, and our Duty to the Congress, we have the honour to be, very respectfully, Sir Your most obedient humble Servants

B Franklin

Silas Deane[1]

When news of the treaties finally reached the American army encamped at Valley Forge, Gen. Washington designated May 6, 1778 as a day for “rejoicing throughout the whole Army.”

[1] “Franklin and Silas Deane to the President of Congress, 8 February 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-25-02-0487. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 25, October 1, 1777, through February 28, 1778, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986, pp. 634–635.]