Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Evan Portman

By the time Ralph Waldo Emerson immortalized the “shot heard round the world” in his 1836 “Concord Hymn”, the battles of Lexington and Concord had already achieved fame as the first engagement of the Revolutionary War. However, in the early twentieth century one West Virginia historian began to argue that the true “shot heard round the world” had occurred six months earlier on October 10, 1774, at the battle of Point Pleasant.

The battle was the culmination of Lord Dunmore’s War, a five-month campaign against the Shawnee and Mingo tribes in an effort to quell the violence along the Ohio frontier.[1] Virginia settlers had begun moving into the Ohio Country following the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, in which the Iroquois Confederacy ceded the territories of present-day Kentucky and West Virginia to the Colony of Virginia. However, the Shawnee had not been consulted regarding the treaty and claimed ancestral hunting rights to the region, responding with violent raids along the frontier to reclaim their land.[2] Virginia Colonial Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore sanctioned the colonial militia to wage a campaign against the Native Americans after white settlers began reacting violently, themselves.[3]

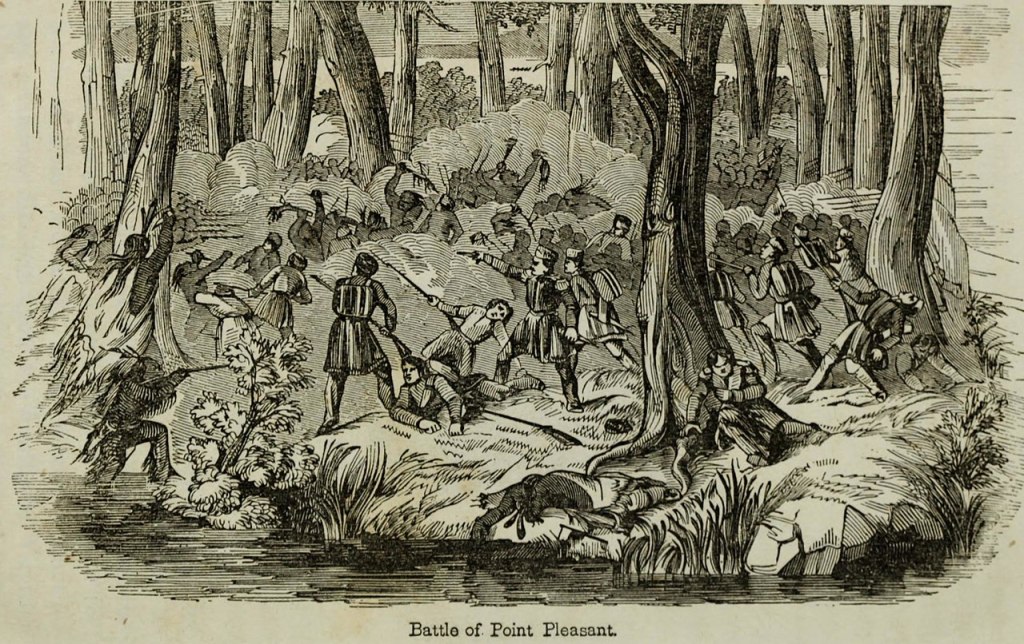

Colonel Andrew Lewis led a force of 1,000 militiamen down the Kanawha River in the hopes of linking up with a column led by Lord Dunmore himself down the Ohio River from Fort Pitt (in present-day Pittsburgh). However, the Shawnee leader Chief Cornstalk planned to intercept Lewis before he could unite with Dunmore’s army.[4] The Native Americans ambushed Lewis and his men in their camp along the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers on October 10, 1774. The Shawnee used the topography to their advantage, hoping to trap the Virginians along a bluff. Fighting lasted for hours and was at times hand-to-hand. Recognizing the precarity of his situation, Lewis ordered several companies up the Kanawha to attack the warriors from the rear. This maneuver allowed the Virginians to gain the upper hand, and the outnumbered Native Americans quietly withdrew back across the Ohio River under the cover of darkness.[5]

Following the battle, Lewis and Dunmore united their columns and pressed their offensive north into present-day Ohio. There, they confronted the Shawnee villages at Pickaway Plains, made temporary camp along the Scioto River (known as Camp Charlotte), and met with Cornstalk to discuss peace negotiations. The battle of Point Pleasant, and subsequent Virginian victory, forced Cornstalk to sign the Treaty of Camp Charlotte and relinquish Shawnee claims to the land south of the Ohio River. He also agreed to return all white captives taken during Lord Dunmore’s War as well as cease any violence toward settlers along the Ohio.[6]

Since the early twentieth century, the idea that Point Pleasant and Lord Dunmore’s War constituted the first battle and campaign of the Revolutionary War has circulated among some circles. Central to this claim is the debate between twentieth century historians Livia Simpson Poffenbarger and Virgil A. Lewis. Poffenbarger unequivocally pronounced Point Pleasant as the first engagement of the Revolutionary War in her 1909 book The Battle of Point Pleasant: A Battle of the Revolution. She likewise held deep ties to the Point Pleasant battlefield and its history. Although she was born in Pomeroy, Ohio, her family moved to Point Pleasant in her early youth. There, she developed a strong connection to the town and its history.[7] Years before publishing her magnum opus, Poffenbarger launched a newspaper campaign to have Point Pleasant officially designated the “first battle of the American Revolution.”

She dedicated her study to “the brave colonists who […] had fought the opening battle of the Revolution, in preserving the right arm of Virginia for the struggle with her Mother Country; thus making possible the blessings of liberty we now enjoy as a Nation.”[8] Throughout her book, Poffenbarger also harkens to other battles of the Revolution, rhetorically linking Point Pleasant to that conflict. When referring to the sacrifices made by General George Washington’s Continental Army, Poffenbarger explains that “the same blood coursed the veins of the patriot army with Lewis at Point Pleasant, the first battle of the Revolutionary War.”[9]

Her reasoning lay in the accusation that Lord Dunmore planned the attack on Cornstalk’s Shawnee to “discourage the Americans from further agitation of the then pending demand for fair treatment of the American Colonies at the hands of Great Britain.”[10] While Poffenbarger cites other historians and participants in Lord Dunmore’s War, her argument is largely uncredible. Few, if any, official documents point to a conspiracy led by Dunmore.

Poffenbarger’s contemporary, Virgil A. Lewis, fiercely contested her claims that the battle of Point Pleasant began the Revolutionary War in any way in his book The History of the Battle of Point Pleasant. Lewis was born within a few miles of the battlefield and, like Poffenbarger, grew up “among the descendants of the men who participated in that struggle.”[11] In fact, Lewis’s great-grandfather—Benjamin Lewis—fought in the battle and, following the Revolutionary War, settled at the mouth of the Kanawha River near Point Pleasant.

While both historians emphasized the importance of Point Pleasant to West Virginia history and the American Revolution at large, they diverged on whether the battle was the first in the Revolutionary War. Lewis argued that, while the first shots of the war may not have occurred at Point Pleasant, the battle between white settlers and Native Americans there did have a positive influence on the subsequent Revolutionary War. He acknowledged that the “substantial peace” secured in the Treaty of Camp Charlotte “there were no Indian wars in these years” during the Revolutionary War. Thus, “the Border men” were free to participate in the war’s most crucial campaigns, including the “overthrow [of] Burgoyne at Saratoga.” For this reason, Lewis directly credits Point Pleasant for leading to the Franco-American Alliance and ultimately to American victory. “This meant France came to the aid of the Colonies; and that meant the Independance [sic] of the United States,” he argued.[12]

While Lewis affirmed the importance of Point Pleasant determining the fate of the republic, he does not classify it as the first battle of the Revolutionary War. Instead, Lewis places it as the last battle of the colonial border wars and the culminating engagement of Lord Dunmore’s War. Lewis also refutes Poffenbarger’s claim that Lord Dunmore orchestrated the battle of Point Pleasant to distract the colonists from the political crisis in the east. “The story of the treachery of Lord Dunmore is shown to have been an after thought,” he concludes, “a thought originating after the Revolution due to his adherance [sic] to his Home Government during that struggle.”[13] Indeed, Virginia delegates Edmund Pendleton and Patrick Henry believed Dunmore had conspired with Indians in order to secure the Ohio Country for himself.

Even Andrew Lewis expressed, during the Revolution, his suspicion that Dunmore halted his column and failed to rendezvous at Point Pleasant because he desired Lewis’s army to be destroyed. This, Lewis believed, was part of Dunmore’s elaborate scheme to weaken the local militia.[14] However, hardly any evidence supports this kind of collusion between the Native Americans and Dunmore.

While Lexington and Concord remain the widely accepted beginning of the Revolutionary War, the battle of Point Pleasant’s place in that history remains somewhat murky. Nonetheless, its significance to America’s founding moment has been maintained and perpetuated by early historians like Poffenbarger and Lewis.

[1] Gregory Evans Dowd, A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 42.

[2] Dowd, A Spirited Resistance, 42-43.

[3] Dowd, A Spirited Resistance, 42-43; Glenn Williams, Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era, (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2017), 8-12.

[4] Lloyd DeWitt Bockstruck, Virginia’s Colonial Soldiers, (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1988), 242.

[5] Williams, Dunmore’s War, 54-58.

[6] Williams, Dunmore’s War, 156.

[7] Nancy Whear, “Livia Simpson Poffenbarger (1862-1937),” in Missing Chapters II: West Virginia Women in History, Frances S. Hensley, ed., (Charleston, WV: Humanities Foundation of West Virginia, 1986), 1.

[8] Poffenbarger, The Battle of Point Pleasant: A Battle of the Revolution, October 10th, 1774, (Point Pleasant, WV: The State Gazette, Publisher, 1909), 3.

[9] Poffenbarger, The Battle of Point Pleasant, 3.

[10] Poffenbarger, The Battle of Point Pleasant, 3.

[11] Virgil A. Lewis, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, Fought between White Men and Indians, at the Mouth of the Great Kanawha River, (Charleston, WV: The Tribune Printing Company, 1909), i.

[12] Lewis, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, 68.

[13] Lewis, History of the Battle of Point Pleasant, 94.

[14] Richard Orr Curry, “Lord Dunmore and the West: A Re-evaluation,” West Virginia History 19(July 1958): 231-43.

Interesting read. Regardless of first battle status or not, the actions there prevented a 2 front situation at the outset of the Revolution. This is somewhat akin to the Regulator argument in NC, a full decade before the Revolution. Some say that was the first battle. Again, regardless, it was the first taste of citizenry aligned against the Colinial royal government in that area. Also the first taste of citizen vs citizen to put down the rebellion. These same folks would need to decide again whether to take up arms and/or jump sides or remain loyal.

LikeLike