Virginian Landon Carter was vocal about the latest pamphlet sweeping through the American colonies in 1776. In several diary entries from the first four months of that momentous year, he commented on Common Sense, written anonymously “by an Englishman.” Carter described its contents in February as “rascally and nonsensical as possible, for it was only a sophisticated attempt to throw all men out of principles.” By April, as he continued to criticize the work, he reached a conclusion about its author: “I begin now more and more to see that the pamphlet called Common Sense, supporting independency, is written by a member of the Congress …” Carter could not have been further from the truth.

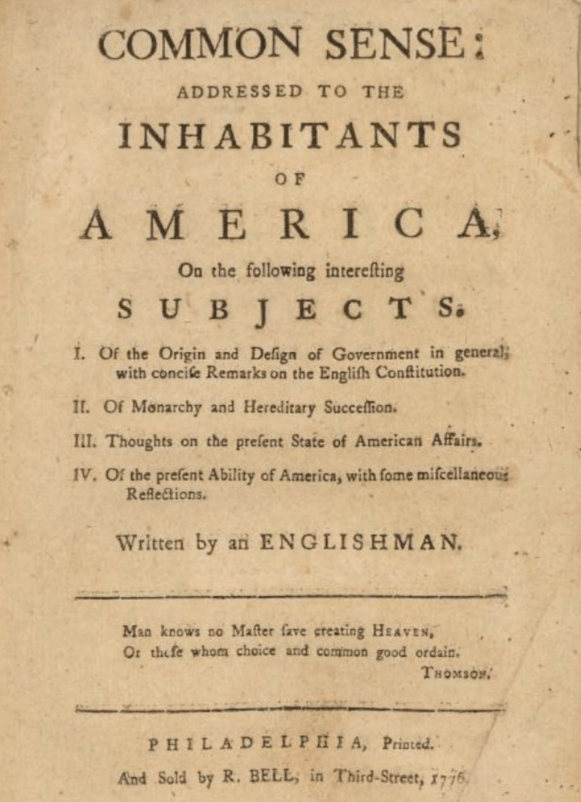

“An Englishman” was, in fact, an apt description for the author of Common Sense, first advertised to the American public on January 9, 1776, and first released on January 10. Thomas Paine was an Englishman—born there and, by most measures, matured there as a failure. He failed at his corset-making business. Teaching, collecting taxes, privateering, and working as a grocer—none of these occupations suited him either. He married twice (his first wife died in childbirth), and his second marriage collapsed. Amid this string of failures, Paine found success with the written word, which caught Benjamin Franklin’s attention in England in 1774. With little left for him in England, Paine embarked for America, arriving later that year. There, he scraped by as a writer, publishing essays in Philadelphia newspapers.

Paine’s time in Philadelphia brought him into contact with men of higher social standing, including figures involved in the Continental Congress convening there. Dr. Benjamin Rush encouraged Paine to express his political beliefs in pamphlet form. The result was a jolt to the American colonies.

The winter of 1775–76 marked a hinge point in the worsening relationship between Great Britain and its American colonies. Blood had been spilled at Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, and Great Bridge. Where would the conflict go next? Congress itself seemed unsure. Historian Robert Middlekauf described Congress’ indecision: “It prepared for war while it begged for peace; it proclaimed its determination to protect American liberties while it petitioned for reconciliation; it expressed respect for the king while it promised death to his armies.” Into this uncertainty stepped Paine and his pamphlet.

While many Americans still hoped that King George III would intervene in the conflict, correct Parliament’s policies, and restore the 1763 status quo, Paine had no use for the king, the British monarchy, or its system of “hereditary succession.” He argued that “the distinction of men into kings and subjects” existed for “no truly natural or religious reason …” Putting the matter in plain terms, he continued, “Male and female are the distinctions of nature, good and bad the distinctions of heaven; but how a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth inquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind.”

Paine continued his attack on monarchy. “For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others forever …. One of the strongest natural proofs of the folly of hereditary right in kings, is that nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an ass for a lion.”

America, Paine reasoned, would be better off severing its connections to European powers, Britain included. The colonies must unite and become their own nation. “The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ‘Tis not the affair of a city, a county, a province, or a kingdom; but of a continent–of at least one-eighth part of the habitable globe. ‘Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected even to the end of time by the proceedings now. Now is the seed-time of continental union, faith, and honor.”

The time for words and offers of reconciliation was over. Colonists and British Regulars had already died fighting one another, and ending the conflict peaceably without separation from Britain was impossible, Paine insisted. “All plans, proposals, etc. prior to the nineteenth of April, i.e. to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacks of the last year; which though proper then, are superseded and useless now.”

To drive his point home simply and forcefully, he concluded, “Everything that is right or reasonable pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ‘Tis time to part.”

Paine’s stinging criticism of the British monarchy and his calls for independence spread rapidly throughout the colonies. His 47-page pamphlet carried the intellectual weight of the movement for separation, tipping the balance between reconciliation and independence decisively in the latter’s favor. American booksellers sold an estimated 120,000 copies of Common Sense in its first three months.

With such wide circulation, Paine’s words reached not only the men representing their colonies in Philadelphia but also the people they represented. A Marylander wrote to a Philadelphia newspaper, “if you know the author of COMMON SENSE, tell him he has done wonders and worked miracles. His stile [sic] is plain and nervous; his facts are true; his reasoning, just and conclusive.” Private Ashbel Green, a New Jersey militiaman, described the pamphlet’s effect more bluntly: “Common Sense struck a strung which required a touch to make it vibrate. The country was ripe for independence, and only needed somebody to tell the people so.”

Though Landon Carter strongly disapproved of Paine’s arguments, General George Washington’s mailbag in Cambridge, Massachusetts, filled with letters from acquaintances in Virginia discussing the pamphlet. “My Countrymen I know, from their form of Government, & steady Attachment heretofore to Royalty, will come reluctantly into the Idea of Independancy,” Washington admitted, “but time, & persecution, brings many wonderful things to pass; & by private Letters which I have lately received from Virginia, I find common sense is working a powerful change there in the Minds of many Men.”

Paine’s words changed minds well beyond Virginia and helped set the American colonies firmly on the path toward independence.

Pingback: In Praise of Common Sense – Emerging Revolutionary War Era

Nicholas Cresswell had this to say about Common Sense on January 19, 1776: “A pamphlet called “Commonsense” makes a great noise. One of the vilest things that ever was published to the world. Full of false representations, lies, calumny, and treason, whose principles are to subvert all Kingly Governments and erect an Independent Republic. I believe the writer to be some Yankey Presbyterian, Member of the Congress. The sentiments are adopted by a great numberof people who are indebted to Great Britain.”

http://www.nicholascresswell.blog

LikeLike

Pingback: Remembering Thomas Paine | The NAKED HISTORIAN