A good friend, knowing my interest in military history brought me a very unique artifact, which led me to discover more about where this piece of history originated from. Here is what I discovered.

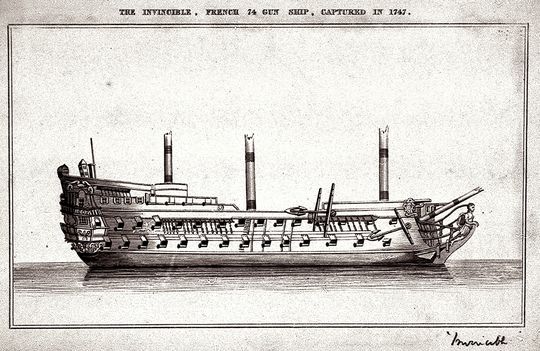

Launched in 1741 by the French as L’Invincible, this 74-gun French ship of line was captured by the British during the First Battle of Cape Finisterre on May 14, 1747.

The engagement during the War of the Austrian Sucession, was a five-hour engagement in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of northwest Spain. The British admiral, George Anson struck the 30-ship convoy of the French, which was under the command of Admiral de la Jonquiere and captured four ships of the line. One of those ships of the line was the L’Invincible.

The L’Invincible sacrificed itself to allow some of the convoy to escape and tried in vain to fend off six British warships.

Given its more Anglicized name; HMS Invincible, the ship’s design was larger than the usual 74-gun vessels of the time. Her greater draft and lower center of gravity allowed her to carry much more sail. This allowed the ship to gain more speed.

Altogether her design helped revolutionize British warship making as she was the first 74-gun ship in the British Navy. By the time of the crucial Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, over three-fourths of the entire British Navy were line ships toting 74-guns.

In February 1758 while part of a large sailing of warships and transports, the HMS Invincible that left from St. Helens Roads near the Isle of Wight in England. The ship struck Horse Tail Sandbank and got stuck. Yet with the rising tide she was able to free herself.

Unfortunately, fate had it in for the ship, as the wind suddenly changed direction and increased in intensity and she dragged her anchor on the sandbank. A failed attempt to lighten her cargo and load of armament and putting her under full sail did not work either. She was marooned on the sandbar and began to take on water.

For the next three days, the majority of her cannons and stores were removed and on February 22, 1758 she rolled onto her side and was lost.

HMS Invincible laid wrecked, covered, and largely forgotten until the 20th century, when in May 1979 a local fisherman snagged his nets on the timbers. Local divers found more of the ship and has been investigated and parts recovered ever since.

One of the interesting finds was the experimental flintlocks of the cannons of the HMS Invincible. Rather large, the nicely knapped flints were believed to be used in the canon locks. Canon locks and subsequent flints among the gunnery stores were considered a “unique find.”

Fore more information about the ship, the wreck, and the discovery, check out Brian Lavery’s The Royal Navy’s First Invincible. Link to the book via Amazon is here.