Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian Gabriel Neville

Most of the enlisted men of the Revolutionary War are faceless and forgotten—just names on lists. Biographies and painted portraits are honors that were reserved for officers. Even so, it is possible to trace the lives of some common soldiers using original sources. Many of them applied for pensions after 1818, which required them to provide (usually brief) narratives of their service. Some gave similar attestations when they applied for military bounty land. A small number left detailed accounts of their experiences in interviews, letters, or diaries. Finally, and very rarely, we have photographs taken in the last years of some veterans’ lives. Virginian John Cuppy may be the only Revolutionary War soldier to leave us an artifact in each of these categories.

Cuppy was born near Morristown, New Jersey on March 11, 1761. While still an infant, he was brought to Hampshire County, Virginia by his German parents. Their new home was on the South Branch of the Potomac River near the town of Romney, which is now in West Virginia. About forty miles west of the Shenandoah Valley, this was the very edged of settled Virginia territory. John was just fourteen years old when the war began—too young to be a candidate for service when Hampshire was directed to raise a rifle company in July of 1775. He was still too young when Dutch-descended Capt. Abel Westfall recruited a company there that winter for Col. Peter Muhlenberg’s new 8th Virginia Regiment.[1]

After his sixteenth birthday, the five-foot-nine, fair-haired, and blue-eyed youth responded to calls to military service four times in four very different fashions: first as an unenlisted volunteer, then as a militiaman, the third time by hiring a substitute, and finally in the 1790s as a full-time soldier under Gen. Anthony Wayne in the Northwest Indian War.[2]

In his 1844 pension affidavit, he asserted that he helped suppress an uprising of Tories in 1777 or 1778. This appears to have been in 1777 since his second period of service demonstrably began in 1778. He told a judge that “he volunteered to serve as an American soldier, in a company commanded by Captain Isaac Means, as he was called, though he thinks his real rank & commission was only Lieutenant.” Cuppy’s recollection here is evidently correct. In 1788, a group of leading Hampshire County citizens opposed Means’ appointment (a promotion, presumably) as a militia captain, calling him “a person of turbulent and quar’elsome disposition.” Cuppy’s reference to the “south fork of the south branch” of the Potomac, places this adventure in the vicinity of Moorefield, now in Hardy County, West Virginia.[3]

The service for which the company was organized was to proceed against a body of tories who had assembled on the South fork of the South branch. There were other companies of volunteers formed for the same purpose about that time: one of these other companies he remembers was commanded by one Ned McCarty. Immediately after Capt. Means company, to which he was attached, was formed, they marched up the South fork [in pursuit] of the tories but found they had been already dispersed by other companies, who held some of them as prisoners. After scouring the neighborhood for a short time, the company returned to Romney, having in charge seven of these tory prisoners whom they confined in Romney jail. The whole time occupied in this actual service was from three to four weeks. The enlistment, or time of volunteering, however, was for three months, the men having been promised that if they would volunteer for that length of time, they should not be held subject then to be drafted. The company continued therefore at home after that, ready at any moment to be called out if their services should be needed before the end of the three months term; but were not again called into service. While on service they drew rations a portion of the time from the government, but the supply of provisions being irregular, they were dependent much of the time for subsistence on the liberality of the Whigs, & especially of the Whig women, in the neighborhoods through which they passed.

Despite the detail Cuppy provided, this service appears to have been discounted when his pension application was reviewed. His claim was denied due to insufficient evidence of at least six months of actual service. His own testimony suggests that he and his neighbors may not have been acting on government authority during this expedition: “The company consisting altogether of volunteers, he thinks was not attached to any regiment or battalion, or at least did not act in conjunction with any other company or force.”[4]

In 1778 Cuppy was drafted for three months to support Gen. Lachlan McIntosh’s expedition from Fort Pitt, ostensibly against the British at Detroit and their Indian allies. The region around Fort Pitt was claimed at that time by Pennsylvania and Virginia, and the two commonwealths competed to govern it. Cuppy visited the newly-constructed Fort McIntosh—north and downstream from Fort Pitt—and helped build Fort Laurens in modern Bolivar, Ohio. It is of this service that we have the best account. Cuppy described it in his 1844 pension application and again in more detail to a historian the year before he died. According to the pension account

He was then drafted for three months as a soldier in the company of Captain Robert Cunningham. The regiment to which this company was attached was commanded by a Colonel or Major Garret Vanmeter, who left them however on the march soon afterwards, & returned home, being unable to travel by reason of sickness or his great personal weight or size. This Militia force was joined with a body of regulars, & the whole body or army, consisting of about three thousand men, was under the command of General Mackintosh. The company joined some of the rest of this force, on their march westward in the Alleghany mountains, but the general rendezvous, where all were at last assembled, was at the mouth of Big Beaver on the Ohio river, where they built Fort Mackintosh.

Leaving five hundred men there, mostly regulars, they then proceeded to the Tuscarawas, in or near what is now Stark County in Ohio, near the mouth of Big Sandy, & built another fort which they named Fort Lawrence. At Fort Lawrence they remained until after the three months for which he was drafted had expired, & to the month of December, for he recollects that he reached home, after he was discharged, on Christmas eve, having been about four months, or within a few days of that period in service.

The reason for his extended services was that “General Mackintosh was occupied during this time in trying to treat with the Indians.” McIntosh already had an alliance with the Delaware, a relationship he hoped to leverage into an attack on the British base at Detroit. The evident weakness of his force, however, was shaking the Delaware Tribe’s trust in him. Consequently, “[h]e would not discharge the soldiers of Captain Cunningham’s company, nor any of the Militia, when their term of draft or enlistment had expired, but threatened them with attack by the regulars, if they should attempt to leave him, until regularly discharged, which was not as before stated until in December.” Despite these extreme measures the alliance with the Delaware did not last long.[5]

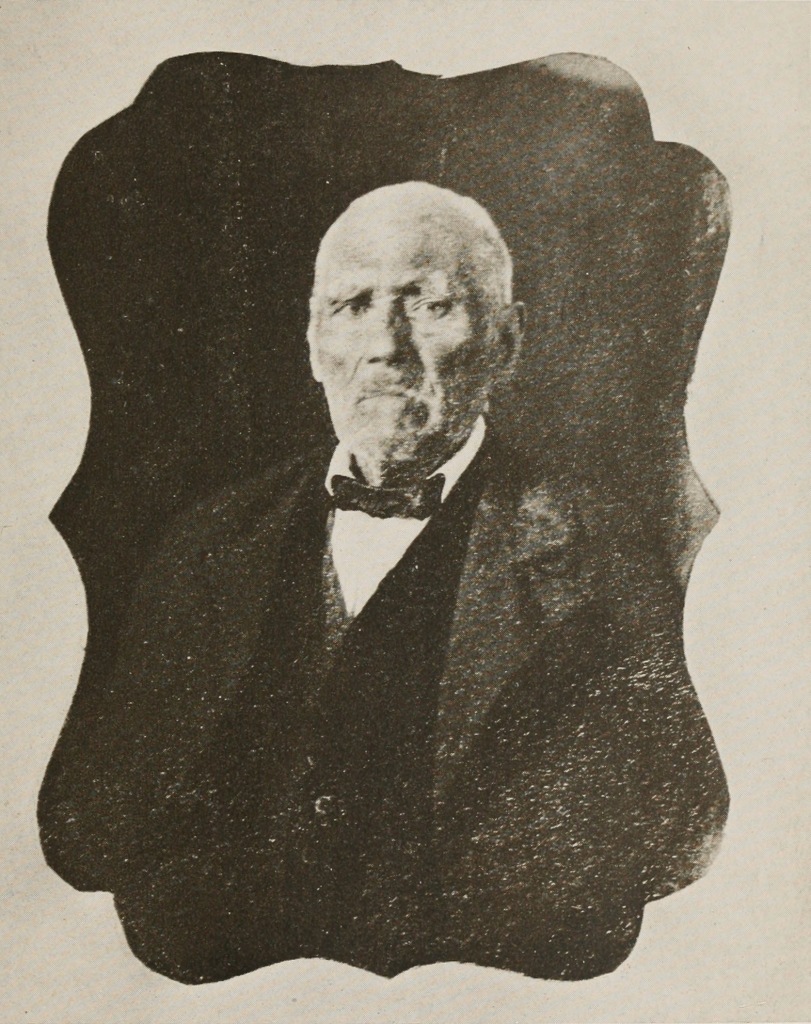

The second account of Cuppy’s service under McIntosh was recorded by historian Lyman Draper, who interviewed him in 1860. At the time of the interview, Cuppy was ninety-nine years old. The photograph of Cuppy was taken at about the same time. Draper (1815-1891) was an officer of the Historical Society of Wisconsin who made it his life’s work to “rescue from oblivion” the stories of southern and frontier Revolutionary war heroes. Draper seems to have been as eager to collect details on the frontier forts as he was to record Cuppy’s personal experiences. The account of Cuppy’s service is in Draper’s voice.

In 1778 a draft came for some Hampshire militia to join General McIntosh in an expedition into the Indian country for a three months service. Started in September. Abram and Isaac Hite went out as commissaries, with a large drove of beeves, and flour packed out on horses, and both went [for] the campaign, my informant knowing them both and seeing them often during the expedition. Captain Vanmeter, who lived at or near Moorfield, commanded the Hampshire company, in which Mr Cuppy served—some 40 in the company. Is not certain whether any other companies went from Hampshire. Probably in Col. William Crawford’s regiment.

Rendezvoused at Pittsburgh, but Van Meter’s company marched directly across the country to mouth of Beaver, and there joined the army, who had already built Fort McIntosh, which was larger and stronger than Fort Laurens; Fort McIntosh, nearly square, stockaded in, enclosing nearly two acres, relying upon the river for water, and the gate was on the opposite side from the river. Pickets went on each side to the water; no pickets next the river. Thinks it was built on a barren and carried and drew in timber for the fort for half a mile. Don’t remember who was left in command at Fort McIntosh.[6] Remembers that Colonels Crawford, [Daniel] Brodhead, and [John] Gibson were on the expedition. Captain [Samuel] Brady was along, in Brodhead’s regiment but did not make his acquaintance. In Fort McIntosh had about the same buildings within as at Fort Laurens, probably somewhat larger, and located to the right and left of the gate, and on the sides as well as front of the fort.

Cuppy notes that he didn’t make Samuel Brady’s acquaintance here because they became very well acquainted a few years later. General McIntosh intended that forts McIntosh and Laurens would be the first two in a chain of forts supporting an expedition against Detroit which (it was now clear) would have to occur the following year. The latter fort would also fulfill a provision of the Treaty of Fort Pitt requiring the Americans to build and garrison a fort on the Muskingum River to protect the main Delaware settlement at Coshocton. However, the season, short enlistments, and lack of supplies prevented McIntosh from reaching the Muskingum. Instead, he built Fort Laurens on the Tuscarawas River (a tributary of the Muskingum) at spot that had been occupied during the French & Indian war by Col. Henry Boquet’s army. It was the best McIntosh could do, but the fort was too far north to protect the Delaware and too far east to serve as an effective staging base for an expedition against Detroit. Cuppy said his work on the fort occupied “the largest part of the time in service.” The project made a deep enough impression on him that he was able to give Lyman Draper a detailed description of the stronghold decades later.[7]

Reached the Tuscarawas by a plain Indian trail, on [Henry] Boquet’s old road. Colonel Crawford had doubtless been out with Colonel Boquet, and probably many others. Where Fort Laurens was built, was no timber, on a high bank, and a barren back for half a mile or more; and the men had to carry in the timber, four or five to a stick. Made mostly of large, hard wood timber, split, some six inches thick, bullet-proof, planted in trenches three feet deep, solidly packed around, and extending fifteen feet above ground. Thinks the fort, which was on the west bank of the Tuscarawas, enclosed about an acre of ground, and was the longest on the river. No pickets along the river bank, no high overlooking ground either near Fort McIntosh or Laurens. The gate was on the west side of the fort, no spring; relied upon the river for supply of water. There was one block house, about 20 feet square, which was directly to the right of the gate, and next to it, and formed a part of the outside in place of picketing: the block house, about six feet above the ground, the block house was made a foot wider on the wall side, and made to over jut, so if Indians came up, the garrison could shoot down through this open jut directly upon an enemy below; and the floor of puncheons on a level with the over jut; and the timbers built up some eight feet, so as completely to protect those within from the enemy without, and port-holes all around about five feet from the floor, and some two or three feet apart, through to which for the garrison to fire in case of an attack, with a rude roof slanting one way and that within the fort. Thinks there were cannon on the expedition. There were also about 2 cabins built on each end of the fort, not quite together and in a line with the picketing, and helped to form the enclosure, and also had over jutting, and with port holes; but smaller than the block house, and these were for shelter for provisions and baggage.

Cuppy also gave Draper a detailed description of life and events on the Tuscarawas, including an interesting and potentially important account of the army’s interaction with the Indians.

The army encamped in the open ground in a semi-circle around Fort Laurens, some distance from the fort, but not so far back as the woods, in tents; every mess, composed of six or seven men, had a tent. All the baggage of the army, flour &c. was packed on horses. Remained the largest part of the time in service, encamped at Tuscarawas, and the troops continued in camp until they commenced the return march, when a garrison was left at Fort Laurens.

Indians were entirely peaceable; no attacks from them during the expedition remembered; frequently visited the camp, and brought fine fat haunches of venison, bear meat and turkies. and presented to the officers, who gave them some of their too beloved fire water in return. The Indians, both men and women would have frequent dances, a hundred or more together, the taller taking the lead, and others falling into the circle, according to their height, the shortest bringing up the rear, and dancing around in the circle, to the rude music derived from beating upon a kettle by an old Indian, intermingled with occasional yells. Simon Girty was among the Indians, and seemed quite a leader among them.

A few of the troops died at Fort Laurens. Remembers Captain White Eyes, the Delaware chief, but can’t say much about him.

Girty was a Scotch-Irish frontiersman who had lived for years as a child in Indian captivity and defected to the British in March of 1778. If Girty was there that fall as Cuppy remembered, it was almost certainly to reconnoiter the fort. On January 21, just weeks after Cuppy and the Hampshire militia headed for home, Girty led a band of Mingo Indians in an ambush of a returning supply column just east of the Fort Laurens. He returned in February with a larger force to lay siege to the fort. [8]

Cuppy does not seem to have told Draper about McIntosh’s forcible retention of the militia beyond the term of their enlistments. He did, however, give him a detailed and personal account of their return home.

On return march, were short of provisions, and scanty for some time before; didn’t have half enough to satisfy their hunger. The beeves got very poor towards the close of November and early December, and some snow had fallen before they left the Tuscarawas, and ground covered with some half a dozen inches of snow while marching from the Tuscarawas to Fort McIntosh. Had but a single small canoe to set the men over the Tuscarawas. The troops, so large a body, beat down the snow, and the travelling was very good, distance was called 77 miles between the two forts. Thinks this return march from Fort Laurens to Fort McIntosh was accomplished in a day and night, some stopping and making a camp fire, sleep a while, and then push on to Fort McIntosh, not in much order, except each company kept together and all were scattered along, perhaps over half the whole distance.

Though the return to Fort McIntosh seems to have gone smoothly, the notion that they marched seventy-seven miles in a day and a night is implausible. The trek home from Fort McIntosh was grueling. Starved and desperate men resorted to theft and to scavenging the months-old carcasses of cattle that had been slaughtered on the outward march.

On the return march, some of Cuppy’s mess had managed from being on guard the night before to secure a small sack of flour, which they carried some distance into the woods and baked up, throwing away the bag, and dividing the bread. But the troops generally suffered for want of food, and the scanty allowance of beef was very poor; and Cuppy met one poor young fellow named John Bell, sitting by the roadside crying, saying he was so weak he could not proceed any further; and Cuppy gave him some of his supply of bread, and encouraged him to renew the march, which he did, and got in, and finally reached the region of the South Branch of Potomac where he belonged. Thinks Bell did not belong to Van Meter’s company. Some of the soldiers were glad to make use of the hides of the beeves that had been killed on the outward march, and crisp them over the fire, and eat them as they could.

At Fort McIntosh, the troops were discharged, after three months service, and returned to their several homes. Cuppy thinks he was some 4 days going across the country from Fort McIntosh to Red Stone [then] to South Branch of Potomac. He had some money to pay his way along; but many had no means, had to beg supplies, and not unfrequently plunder the fowls of the settlers along the route. Cuppy reached home, in good health, on Christmas eve, 1778.[9]

After making it home again, Cuppy focused on domestic pursuits for the next two or three years. He got married shortly before he was drafted again. His pension affidavit includes an account of his final Revolutionary War service, which was brief. He was unsure of the year, but events and his stated age suggest it was 1780 or 1781.

The said John Cuppy’s next enlistment as a soldier, was when again drafted for three months, in the fall, he believes it was, either of the year 1779 or 1780. After being drafted he was required to hold himself in readiness to march at any time to join the army at the East. He continued to hold himself thus ready for marching orders for a period of two weeks, & then without having yet received orders, or being attached to any company, he hired a man by the name of John Devore who went & served in his place for the remainder of the three months. He gave to this substitute in money, clothes, two cows &c, nearly everything he owned in the world, in order to get him to go in his place, not because he was deficient in courage or patriotism, but because being then only between nineteen & twenty years old he had just married a wife a little younger than himself & could not think of leaving her when it was possible to be relieved from such necessity.[10]

Fort Detroit remained in British hands at the end of the Revolution. Though the Northwest Territory (the area northwest of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi) was ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Paris, the British continued to occupy the fort and encourage Indian attacks on the frontier. Failed attempts to suppress the Indians were made in 1790 and 1791, the second of which was a spectacular and politically embarrassing failure for the Washington Administration. A large, professional army was then sent under Gen. Anthony Wayne in 1792. This three-year campaign concluded with an American victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, when Cuppy was thirty-four years old. Though not part of the Revolution, the campaign settled the Revolution’s most important unfinished business. Fifty-eight years later, in 1850, Congress passed a bounty lands act for veterans who had served in the War of 1812 or in “any of the Indian Wars since seventeen hundred and ninety.” Cuppy, who qualified under the latter provision, appeared before a justice of the peace in Montgomery County, Ohio to describe his service. He was ninety years old.[11] He declared under oath that he

was a private in the Company of Rangers under the command of Captain [Samuel] Brady, in the Indian Wars. That he volunteered at Washington in the State of Pennsylvania some time in year one thousand seven hundred and ninty one, or one thousand seven hundred and ninty two for the term of three years, and that he continued in actual service in said War for the term of three years – and that he was discharged at Washington Pennsylvania some time in the year one thousand seven hundred and ninty four, or five by Colonel Beard.

His daughter, Anne Moore of Tippecanoe County, Indiana gave testimony attesting to his service. She said he “served as a ranger or spy for the space of Two years or upwards, that said service was performed in or about the years A.D. 1792 and 1793… under Captain Samuel Brady… in Ohio… during the Indian war… [when] she was but about Ten years of age.” This application, unlike his first one, was successful.[12]

In 1916 the Historical Society of Wisconsin published Frontier Advance on the Upper Ohio, 1778-1779. It was one in a series of books that collected original documents from the northwest frontier, based largely on Lyman Draper’s research and collections and edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louise Kellogg. The photograph of Cuppy was published in the volume along with Cuppy’s recollections. The image is in the society’s collections. Though the society’s catalogue says the photographer is unknown, it seems likely that Draper arranged for the photograph to be taken. In a footnote, Kellogg summarized John Cuppy’s life, relying on Draper’s notes and her own expertise to provide some context. She does not, however, seem to have had access to Cuppy’s pension and bounty land applications. “John Cuppy,” she wrote, “of German parentage, was born Mar. 11, 1761, in New Jersey; while he was an infant his father removed to the south branch of the Potomac in Hampshire County. Thence John was drafted for McIntosh’s expedition, his first military service. The next year he married, and took a tour of military duty during the Loyalist insurrection of 1781. About the year 1788 he removed to a farm near Wellsburg, W. Va., where he engaged in the spy service under Capt. Samuel Brady, and became an expert rifleman and scout. In1818 he removed to Ohio, and in 1823 settled in Wayne Township, Montgomery County. There Dr. Draper secured from him these reminiscences, Aug. 21 to Aug. 23, 1860. He died the following year having completed a century of life.” Without the benefit of Cuppy’s pension documents, Kellogg was unaware that he lived for a time after his service with Wayne in Dearborn County, Indiana. She also seems to have assessed wrongly that his campaign against local Tories was connected with Claypool’s Rebellion, a significant uprising that was put down by Daniel Morgan in 1781.[13]

Over the span of one hundred years John Cuppy had witnessed and participated in the dramatic creation and expansion of the United States. He lived just long enough to also see it begin to unravel. He died two and a half months after the Confederate cannons opened fire on Fort Sumter.

*Bio*

After twenty-five years working in journalism and state and national politics, Gabe Neville now serves as a senior advisor at Covington & Burling LLC, a law firm in Washington, DC. He lives with his wife and children in Fairfax County, Virginia. You can follow his work at 8thVirginia.com and Facebook.com/8thVirginia.

[1] Pension Application of John Cuppy R2590, transcribed and annotated by C. Leon Harris, RevWarApps.com; Louise Phelps Kellogg, Frontier Advance on the Upper Ohio, 1778-1779, (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1916), 158; William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large, Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619, 13 vols. (Richmond: J. & G. Cochran, 1819-1823), 9:9-14, 75-92, E.M. Sanchez-Saavedra, Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the Revolution (Richmond: Virginia State Library), 27-38. Sanchez-Saavedra’s survey of Virginia military units seems to indicate that Hampshire failed to produce a company in 1775. The text of Cuppy’s pension is unaltered except to correct the spelling of “Romney.” The author has observed some discrepancies between Cuppy’s account and genealogical postings on the Internet. No attempt is made here to resolve these conflicts.

[2] Cuppy Pension. The physical description was given by his second wife in 1882.

[3] Cuppy Pension; William P. Palmer, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts (Richmond: R. U. Derr, 1844) 4:501.

[4] Cuppy Pension.

[5] Cuppy Pension; Kellogg, Frontier Advance, 24, 172-175, 183-184.

[6] Virginia Lt. Col. Richard Campbell was left in command. See Gabriel Neville, “Shenandoah Martyr: Richard Campbell at War,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 3, 2019.

[7] Eric Sterner, “The Treaty of Fort Pitt, 1778: The First U.S.-American Indian Treaty,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 18, 2018.

[8] Eric Sterner, “The Siege of Fort Laurens, 1778-1779,” Journal of the America Revolution, December 17, 2019.

[9] Lyman Draper, “Recollections of John Cuppy,” in Frontier Advance, 158-161, citing Draper mss., Historical Society of Wisconsin collection, 9S2-7.

[10] Cuppy Pension.

[11] “An Act granting Bounty Land to Certain Officers and Soldiers who have been engaged in the Military Service of the United States,” Statutes-at-Large, 31st Congress, First Session, September 28, 1850, Library of Congress.

[12] Cuppy Pension.

[13] Kellogg, Frontier Advance, 158.