The Revolutionary War has more than its share of adventurers, rogues, soldiers-of-fortune, and risk-takers. Augustin Mottin De La Balme combined all these characteristics in his person. In November 1780, they brought the Frenchman and his soldiers to a horrible end outside the Miami Village of Kekionga, near the confluence of the Saint Joseph, Saint Mary’s, and Maumee Rivers in modern Fort Wayne, Indiana.

La Balme was born in France in 1736, entered the Gendarmerie in 1757, served in the seven Years War, gained experience in the cavalry, received an army appointment in 1763, and retired with a pension in 1773. He wrote several books on cavalry training and tactics, but finding his fortunes stalled, left for America in 1777 with a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, just one more French officer seeking rank, advancement, and his fortune in the war against Great Britain.[i] Major General William Heath, who met him in Boston, wrote Washington, “We swarm with French Officers at this Place, Two arrived in the Ship on Sunday at this Place They are much Superior to any that I have as yet Seen, One is an Engineer The other a Captain of Cavalry, They are Gentlemen of Education, Sense and Genius, The Captain has with him Two Treatises on the Discipline and management of the Horse, written by himself, and much Approved by all the Generals in the French Service.”[ii] Despite a glut of would-be foreign officers, La Balme received a commission as a Lieutenant Colonel and then Colonel and Inspector General of Cavalry. Dissatisfied with the appointment, he resigned, focused his attention on mobilizing Frenchmen still living in North America, and kept petitioning Congress to find useful work for him. Eventually, Congress tried to pay him off and send him home, but the French officer stayed, trying his hand at various schemes to contribute, including mobilizing Indians in Maine to attack the British. That short-lived campaign accomplished nothing, but resulted in La Balme’s capture and eventual escape.[iii]

June, 1780 found La Balme at Pittsburgh where he joined forces with Godfrey Linctot, a French Canadian who had been agitating to mobilize France’s old Indian allies and subjects in the west for a march on Detroit. He apparently had the support of France’s minister in Philadelphia and Colonel Daniel Brodhead, commanding at Fort Pitt.[iv] La Balme reported to the French Minister, the Chevalier De La Luzerne, that Linctot arranged a meeting between leaders from several Native American nations and La Balme as the representative of the French government at Fort Pitt. La Balme alternated between threatening the Indians if they joined the British and cajoling them to join the French and Americans in exchange for support. For their part, the Indians complained of lack of material support from the Americans and French and constant threats by the British, to which the Americans had not responded.[v]

La Balme set off for the west to Vincennes on the Wabash River in western Indiana. Founded by the French, the town had already changed hands three times during the war, from the British to the Americans, back to the British, and then back to the Americans. He arrived in July and concluded that the Virginians who controlled the town had alienated the majority-French population.[vi] This may have served La Balme’s purpose well enough as a Frenchman claiming the support of the French minister and government. His plan was to raise as many Frenchmen as he could on the frontier and march on Detroit, the former locus of French power in the far west before being lost to the British after the French and American War. Detroit still had a significant French population, which, theoretically, was emotionally, culturally, religiously, linguistically, and (hopefully for La Balme) politically French. Much the same could be said of the European towns along the Mississippi, especially Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Prairie Du Rocher. Even across the Mississippi, many of the Spanish-governed towns, like St. Louis, had been founded by Frenchmen crossing the river to avoid becoming British subjects after the French and Indian War. So, just as George Rogers Clark had hoped to find people opposed to the British government on the frontier when he arrived in 1778, so too did La Balme in 1780.

During August, La Balme tried to recruit locally in the Illinois Country, from Vincennes in the east to St. Louis in the west and the Illinois towns nearby. Everywhere, he reportedly heard complaints from the locals about the Virginians who had invaded and controlled their region since Clark’s arrival. La Balme pledged that the French king was coming to their aid and sought to raise a force of local French and allied Indians to march on Detroit. He was in St. Louis on September 17 and Cahokia across the river on September 21.

La Balme may have been in search of soldiers, but the locals were in search of an advocate. They felt ignored or abused by the Virginians who governed the area and might welcome French intervention. The people of Cahokia informed him, “we ask you to be willing to interest yourself in our grievances and speak in our favor. May the heavens bring it about that by your intervention we may be able to attain that to which we aspire, which is nothing less than the happiness of seeing ourselves again all French. We have nothing to offer you in hostage except the greatest fidelity of heart which we shall never cease having.”[vii] In other words, they had much to ask, but little to offer. The phrase “the happiness of seeing ourselves again all French” raises questions about what promises La Balme made to the locals in order to encourage enlistments. He represented himself as an agent of the king and may have hinted that the French government would take control of the region again once the English were defeated, which at least some people in Cahokia apparently wanted.

La Balme was in Kaskaskia by September 24, still seeking recruits, and reportedly promising that French troops would arrive in the spring of 1781.[viii] (It was likely a counterproductive promise; why would anyone risk life and limb to attack Detroit in the fall of 1780 if French professionals were expected the next spring? La Balme was clearly new at politics.) He stayed at Kaskaskia, still raising troops from among the French locals and as many Indian nations as he could convince. Richard Winston, a local, wrote in his diary:

There passed this way a Frenchman, called himself Colonel de la Balm, he says in the American service. I look upon him as a malcontent, much disgusted at the Virginians, yet I must say he done some good, he pacified the Indians. He was received by the inhabitants just as the Hebrews would receive the Messiah, was conducted from the post here by a large detachment of the inhabitants as well as different tribes of Indians. He went from here against Detroit being well assured that the Indians were on his side. Got at this place and the Kahos about fifty volunteers. They are to rendezvous at Ouia.”[ix]

Winston wasn’t alone in detecting dissatisfaction with American governance among the locals. Captain Richard McCarty, posted at Fort Bowman in Cahokia, also noted frequent complaints about the Virginians who had seized the Illinois Country from the British in 1778. Clark’s occupying force often drew upon them for supplies, but could only offer promissory notes as payment. After La Balme began circulating in town, McCarty noted, “the people in General seem to be Changed towards us and Many things Said unfitting…as things are now the people in General are alienated and Changed from us.”[x]

La Balme’s address to his soldiers, all fifty of them, seemed to put an end to the question of who would govern the Illinois Country when the British were defeated. He berated American authorities in the region, arguing that the Americans would sacrifice Frenchmen as cannon fodder and generally treat them as slaves. Then, he promised French aid: “The mother country reaches out to you her arms in aid. She wishes not to conquer but to rule you by wise laws in order to make you happy. She aspires only to unite herself to you, only to send back to your country the abundant streams of products of her soil.”[xi] An enemy of the British to be sure, La Balme was no friend of the Americans. He seemed to promise to undo George Rogers Clark’s “conquests” of 1778/1779 in favor of returning the region to French control.

La Balme and roughly 41 men finally set out on from Cahokia on horseback on October 3, bound for a rendezvous at Ouiatenon, upriver on the Wabash roughly where today’s West Lafayette, Indiana is. It was the site of some Wea Indian villages, a trading post, and an abandoned French fort. He was still there on October 18 assessing his force and organizing it for the march on Detroit. From there, he departed for the Miami Nation’s capital at Kekionga at the junction of the Saint Mary, Saint Joseph, and Maumee Rivers, roughly where Fort Wayne stands today, with roughly 103 men, French and Indians. The Miami had been among the most consistent British-allied frontier raiders. Storehouses belonging to the French Canadian traders Beaubien and LaFontaine, both of whom had family among the Miami, were in the town, but Kekionga’s warriors were away. Seeing the trader’s storehouses, La Balme end his men looted them in an “orderly” fashion. They set some goods apart to supply their operations and divided the rest to provide pay the soldiers and future recruits, some as bounty, and some as compensation for the Indians.[xii] La Balme expected reinforcements to join him at Kekionga, eventually enlarging his group to some four hundred Frenchmen and Indians. So, he waited nearly two weeks, during which period he sought to prevent any Miami in town from leaving. When no reinforcements were forthcoming, the Frenchman dispatched his plunder to Aboite Creek, some sixteen miles back down the trail in the direction of Ouiatenon.[xiii]

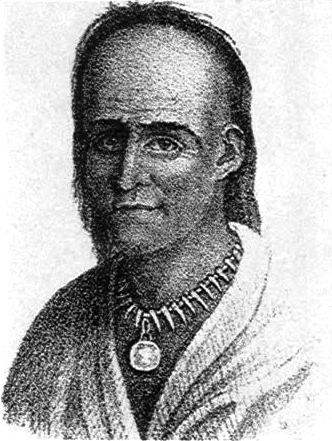

The long stay at Kekionga, of course, gave the Miami ample time to mobilize their warriors. Egged on by Beaubien and LaFontaine, they waited until La Balme was most vulnerable. When he split his force between Kekionga and Aboite Creek, the Miami attacked, led by war captain Meshekinnoquah, known by whites as Little Turtle, and a French officer. They waited until the middle of the night, surrounded the camp, and struck from all sides. If La Balme had posted a picket, it was inadequate to provide sufficient warning.[xiv] Most in La Balme’s contingent were killed or captured. The British lieutenant governor at Detroit, Major Arent Schuyler De Peyster, reported on November 13:

“A detachment of Canadians from the Illinois and Post Vincent arrived there (at the Miami’s town) about 10 ten days ago, and entered the village, took the horses, destroyed the horned cattle, and plundered a store I allowed to be kept there for the convenience of the Indians, who soon after assembled and attacked the Canadians, led by a French colonel, whose commission I have the honor to enclose. The Miami, receiving the fire of the enemy, had five of their party killed, being however, more resolute than savages are in general, they beat off the enemy, killed thirty and took LaBalm prisoner…You will see from this that the excursion was no less an attempt on Detroit, independent of the rebels.”[xv]

In truth, the British were largely in the dark about events on the Wabash. DePeyster and his superior, Governor Frederick Haldimand, had been unaware of La Balme’s advance and were uncertain about events at Kekionga. Within a few days of notifying Haldimand of La Balme’s retreat, DePeyster forwaded additional information: the Miami had been surprised at Kekionga; La Balme was dead along with up to forty of his men; La Balme had given up the campaign and begun withdrawing from Kekionga when he was attacked; Detroit was vulnerable to the kind of campaign La Balme envisioned; and that he had dispatched his own Rangers to remain stationed at Kekionga in order to prevent another surprise.[xvi]

The La Balme campaign was one of those odd episodes in American history that rarely rates a mention. It was tiny, ad hoc, and failed without accomplishing anything. But, it does highlight some important issues. While disappointing, his recruiting efforts in the Illinois Country during the summer of 1780 revealed cracks in the edifice of American control. Indeed, that summer George Rogers Clark was away conducting a campaign against the Shawnee in central Ohio, resulting in victory at the Battle of Peckuwe in August. Even as La Balme was promising a return of French control, American officials were concerned that the locals had turned against them. The area might be easily separated from the Americans and returned to the British, or perhaps even the French should either commit sufficient resources. Detroit was vulnerable. La Balme’s success in surprising Kekionga indicated that British and Miami intelligence about threats from the Illinois Country was unsatisfactory. Even more, DePeyster conceded to Haldimand that Detroit’s own French population was restless and that the fort in Detroit was short of troops. Had La Balme succeeded in raising 400 soldiers and Indians, DePeyster feared they might cause significant problems. Finally, the Miami decided to deal with La Balme on their own, rather than appealing to the British for help. Americans often viewed the Native Americans as lackeys of the British, which was far from the truth. Like most Indian nations, the Miami had their own agenda during the war and were prepared to pursue it with, or without, British help. As a source of supply, the British might be able to influence Native American behavior, but they hardly controlled their native allies. Indeed, the skirmish at Kekionga, known sometimes as the La Balme massacre, marked the emergence of a new generation of Native American leaders. Little Turtle rose to prominence after his victory and became one of the war leaders when a confederacy of western Indian nations resisted American advances into the northwest territory after the Revolution. Together with the Shawnee leader Bluejacket, he led the Indian Army that defeated Arthur St. Clair in 1791.

[i] “Mottin De La Balme,” Mark M. Boatner, III, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1994 ed.), 748-749; Clarence M. Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” Illinois Historical Society, Transactions for the Year 1909, (Springfield, IL: Illinois State Historical Library, 1909), 104.

[ii] “To George Washington from Major General William Heath, 23 April 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0233. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 9, 28 March 1777 – 10 June 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 244–246.]

[iii] Boatner, 49.

[iv] “French Agent at Fort Pitt, Summary of a letter of Col. Mottin de La Balme, Fort Pitt, June 27, 1780, to Chevalier de la Luzerne,” note 2, Louis Phelps Kellogg, ed., Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 1779-1781 (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1917), 200-201; Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 108-109.

[v] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 110-111.

[vi] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 112.

[vii] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 113. Emphasis added.

[viii] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 114.

[ix] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 114, note 1.

[x] Clarence Alvord, The County of Illinois, Reprinted from Illinois Historical Collections, Volume II (Chicago: Illinois State Historical Society, 1907); “Richard McCarty to John Todd, Jr., 14th Oct’r 1780,” James Alton James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers, 1771-1781, Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library, Volume VIII, Virginia Series, Volume III, (Springfield, IL: Illinois State Historical Library, 1912), 459-461.

[xi] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 116.

[xii] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 117.

[xiii] Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 117. Exactly when La Balme moved his plunder to Aboite Creek is uncertain. It may have been earlier in his occupation of Kekionga, meaning his forces were split for several days.

[xiv] Calvin M. Young, Little Turtle: The Great Chief of the Miami Indian Nations (Greenville, OH: Calvin Young, 1917), 34-35; Little Turtle, 1752-1812 (Fort Wayne: The Allen County-Fort Wayne Historical Society, 1960), 14-15.

[xv] Quoted in Burton, “Augustin Mottin De La Balm,” 117-118. DePeyster later learned that La Balme had been killed during the brief battle. “Major Arent S. De Peyster to Brig. Gen. H. Watson Powell, 13th Nov. 1780,” Collections and Researches Made by the Pioneer and Historical Society of the State of Michigan, Historical Collections, Vol. XIX (Lansing, MI: Thorp & Godfrey Printers, 1892), 581-582.

[xvi] “Major De Peyster to General Haldimand, 16th Novr. 1780,” Collections and Researches Made by the Pioneer and Historical Society of the State of Michigan, Historical Collections, Vol. X (Lansing, MI: Thorp & Godfrey Printers, 1888), 448-449.