Reverend John Gano served as a pastor of a Baptist Church in New York City before the Revolution. When the British occupied the city, his congregation split and dispersed. Although he resisted attempts to recruit him as a chaplain, the minister accepted an invitation to preach to a Continental regiment on Sundays until the Royal Navy cut him off from Manhattan. Recalled Gano, “I was obliged therefore, to retire, precipitately, to our camp.”[1] The preacher would become a chaplain after all. Gano joined Colonel Charles Webb’s Connecticut Regiment and followed it.

Gano stayed with the army, was there during the battles in New York and mistakenly found himself in front of his regiment at White Plains. He remained with the unit until enlistments expired at the beginning of 1777. The minister pledged to rejoin if Webb and his officers raised a new regiment, but instead found himself at Fort Montgomery on the Hudson, eventually succumbing to arguments from General James Clinton and Colonel “Dubosque” to join the men stationed there as a chaplain. (This was probably Colonel Lewis Dubois of the 5th New York.) He remained there until Sir Henry Clinton launched his autumn attack into the Hudson Highlands to support General Burgoyne’s campaign to Albany. Allowing for the uncertainties and errors of first-hand experiences and perspectives, the happenstance-chaplain provided an excellent first-hand account of the battles for Fort Montgomery and Fort Clinton on October 6, 1777.

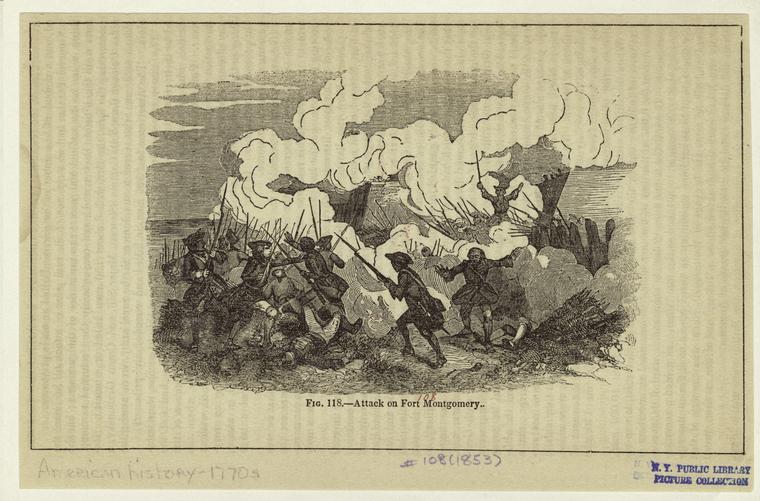

“We had, both in Fort Montgomery, and Fort Clinton, but about seven hundred men. We had been taught to believe, that we should be reinforced, in time of danger, from the neighbouring militia; but they were, at this time, very inactive. We head of the approach of the enemy, and that they were about a mile and a half from Fort Clinton. That fort sent out a small detachment, which was immediately driven back. The British army surrounded both our forts, and commenced universal firing. I was walking on the breastwork, viewing their approach, but was obliged to quit this station, as the musquet balls frequently passed me. I observed the enemy, marching up a little hollow, that the might be secured from our firing, till they came within eighty yards of us. Our breast-work, immediately before them, was not more than waist-band high, and we had but a few men. The enemy, kept up a heavy firing, till our men gave them a well directed fire, which affected them very sensibly. Just at this time, we had a reinforcement from a redoubt, next to us, which obliged the enemy to withdraw. I walked to an eminence, where I had a good prospect, and saw the enemy advancing toward our gate. This gate, faced Fort Clinton, and Captain Moody, who commanded a piece of artillery at that fort, seeing our desperate situation, gave the enemy a charge of grape-shot, which threw them into great confusion. Moody repeated his charge, which entirely dispersed them for that time.

About sun-set, the enemy sent a couple of flags, into each of our forts, demanding an immediate surrender, or we should all be put to the sword. General George Clinton, who commanded Fort Montgomery, returned for answer, that the latter was preferable to the former, and that he should not surrender the fort. General Hames Clinton, who commanded in Fort Clinton, answered the demand in the same manner. A few minutes after the flags had returned, the enemy commenced a very heavy firing, which was answered by our army. The dusk of the evening, together with the smoke, and the rushing in of the enemy, made it impossible for us to distinguish friend, from foe. This confusion, have us an opportunity of escaping, through the enemy, over the breastwork. Many escaped to the water’s side and got on board a scow, and pushed off.”[2]

In his recent history of the Saratoga Campaign, Kevin Weddle cites General Clinton’s estimate of 350 American casualties: 70 killed, 40 wounded, and 240 captured, roughly half of the combined garrison of both forts. (Weddle estimates the American garrison at 700, not the 800 Gano believed). British losses amounted to forty killed and 150 wounded out of 2,150 in the assaulting forces.[3]

Gano spent the remainder of his service in the northeast, accompanying the men during General Sullivan’s campaign against the Iroquois, but otherwise spending the time in encampents. He finally returned to New York and reoccupied his house after war: “My house needed some repairs, and wanted some new furniture; for the enemy plundered a great many articles.”[4] After the war, the minister rebuilt his congregation in New York before relocating to Kentucky, where he died in 1804.

[1] Biographical Memoirs of the Late Rev. John Gano (New York: Printed by Southwick and Hardcastle for John Tiebout, 1806), 93.

[2] Ibid., 98-100.

[3] Kevin Weddle, The Compleat Victory: Saratoga and the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 300, 302.

[4] Biographical Memoirs of the Late Rev. John Gano, 116.