Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian, Nathaniel Parry, a brief bio follows this post.

The American Revolution was a victory of liberty over tyranny made possible by a mixture of courage, grit, and virtue. It was also, however, a morally ambiguous affair with some of the main participants motivated as much by ambition as they were by idealism. While many of the founding generation prided themselves on their virtue, vice also played an important role in their rebellion against the British, and to fully appreciate this reality, it is useful to examine the role of alcohol, which turns up at many of the revolution’s key moments.

In ways sometimes subtle and often quite important, alcohol provided the impetus for the nation’s founding, belying the pristine image of an honorable rebellion of virtuous patriots against liberty-hating tyrants. From John Hancock celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766 by “treat[ing] the Populace with a Pipe of Madeira Wine,” as one newspaper reported,[i] to militiamen wetting their whistles at Buckman Tavern before the Battle of Lexington and Concord,[ii] to General George Washington ordering “an extra ration of liquor to be issued to every man”[iii] in celebration of Britain’s recognition of America’s independence in 1783, alcohol pops up again and again during the revolutionary era. This was a reflection of the fact that drinking was an integral part of daily life in early America.

With heavy drinking habits widespread among all classes and regions, the rum distillery industry flourished in the colonies, made possible by cheap imports of molasses from the West Indies. By one count, there were more than 150 rum distilleries in New England before the revolution, and throughout the colonies some five million gallons of rum were being produced.[iv] In order to ensure access to the cheapest molasses available and to bypass restrictive English regulations such as the Navigation Acts and 1733 Molasses Act, smuggling became rampant in the colonies, a problem that Parliament sought to address with the adoption of the Sugar Act in 1764. An attempt to crack down on smuggling and increase revenue, the Sugar Act had the effect of increasing the price of manufacturing rum and negatively affected the exporting capacity of New England distillers, leading to consternation among merchants. It also heavily taxed the formerly duty-free wine from Madeira, Portugal, which was popular throughout the colonies. This angered both merchants and consumers.[v]

Samuel Adams led the charge against the Sugar Act, drafting a report for the Massachusetts General Court in May 1764 that denounced the measure as an infringement on the rights of the colonists, as well as a threat to commerce. Adams presciently warned that “if our Trade may be taxed why not our Lands? Why not the produce of our Lands, and every Thing we possess or make use of?”[vi]

In response to the Sugar Act, dozens of Boston merchants banded together in a boycott of British luxury imports, and there were movements to increase colonial manufacturing. Meanwhile, smuggling continued, which often led to friction with royal authorities. In the so-called Liberty Affair of 1768, riots erupted after an attempt to seize John Hancock’s sloop Liberty which had arrived in Boston from Madeira on May 9 with a cargo full of wine. Authorities attempted to seize the ship, which led to what John Adams later referred to as “a great Uproar [being] raised in Boston, on Account of the Unlading in the Night of a Cargo of Wines from the Sloop Liberty from Madeira.”[vii] A mob assaulted Customs Collector Joseph Harrison and Benjamin Hallowell, Comptroller of the Port of Boston. The patriots tore off the men’s clothes and bludgeoned them with clubs and stones,[viii] then smashed the windows of the customs officials’ houses, and set Harrison’s pleasure boat on fire on Boston Common.[ix] Some accounts say that as many as 2,000-3,000 rioters took part in the melee, while others say it was several hundred.

***

In response to the Liberty Affair, British officials increased the troop presence in the city, leading to tensions that ultimately resulted in all-out war. Altercations that arose between occupying British soldiers and local Bostonians were sometimes attributed to the redcoats treating the town as a garrison post where they felt they had license to drink freely, leading to occasional assaults on women and other incidents. The redcoats were fond of cheap New England rum and their attitudes toward the colonists appeared at times to be a mix of envy and contempt. In his written accounts of the occupation, Samuel Adams tended to amplify every altercation between Bostonians and the occupiers, for example highlighting incidents in which the troops attempted to court the wives of the locals. His articles in the Boston Evening Post, for example, told tawdry tales of girls brutalized after refusing advances of randy redcoats, helping to fuel the animosities that would later result in the Boston Massacre.[x]

After war broke out in spring 1775, alcohol turns up again at key moments. On May 10, 1775, Ethen Allen, Benedict Arnold and the unruly Green Mountain Boys descended on Fort Ticonderoga’s British garrison to seize the armaments and send them to Boston for the siege underway. As many as 400 men arrived at the fort, which they took over without a fight, and before setting about in their important mission of plundering the weapons, they first helped themselves to the provisions of liquor. Allen justified the seizure for “the refreshment of the fatigued soldiery,” and his Green Mountain Boys proceeded to drink all 90 gallons of rum.[xi]

The following year, alcohol turns up again at the Battle of Trenton, a key turning point in the Revolutionary War. According to some accounts, the pivotal battle in the winter of 1776 may have been influenced by the Christmas night overindulgence of the German Hessian troops, but many historians have pushed back on this claim, arguing that it is little more than a myth.

What is known is that in late 1776, following a disastrous series of defeats in the New York campaign, General Washington desperately needed a battlefield victory, and he looked to the garrison of 1,500 Hessian mercenaries at Trenton as an attractive target for a surprise attack. After a difficult march to the Delaware River and an even more difficult crossing, which had been complicated by a strong storm that brought freezing rain and winds, Washington’s 2,400 troops attacked the Hessian troops quartered at Trenton on December 25. The Continental soldiers quickly overpowered the German mercenaries, capturing more than 1,000 enemy troops in the brief skirmish. The victory proved to be a major boost to the fledgling cause of independence.[xii]

Whether the Hessians were actually drunk though is another question. It seems that the legend of inebriated Hessians originates from the time period, when British officers began circulating the story to excuse the embarrassing defeat and deny the Americans some of the glory of their victory. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that it might be unfounded. Contrary to the notion of the Hessians being heavily impaired, Washington told Congress that the Hessians “behaved very well” and maintained “a constant retreating fire from behind houses.”[xiii] Continental soldiers who participated in the battle also rebutted the claims, noting that they did not see any intoxicated Hessians. “I am willing to go upon oath that I did not see even a solitary drunken soldier belonging to the enemy,” wrote John Greenwood.[xiv]

Of course though, just as the Brits may have exaggerated the possibility of drunken Hessians to deny the Americans their glory of victory, the Continentals also may have downplayed this story for the opposite reason, and whether or not all or even some of the Hessians were impaired, it seems that their commander may have been. Colonel Johann Rall apparently didn’t take seriously some warnings that he had received from informers of an imminent attack and was famously playing cards on the night of the attack. “Rhall seeing so little precaution taken by the general, looked upon the intelligence as false, and got drunk as usual,” reads an account from 1780.[xv]

Whether or not alcohol affected the actual fighting, it certainly featured prominently following the defeat of the Hessians, with some Americans, after taking over the garrison, breaking into the rum supply and heartily celebrating their victory.[xvi] This made the return trip after the battle in some ways more difficult than the first crossing of the Delaware. Due to the large number of intoxicated soldiers, the second crossing was slowed down considerably by the frequent stops to rescue troops who fell overboard into the icy waters.[xvii]

Incidentally, the looting of the Hessians’ rum supply was in direct contravention of Washington’s explicit orders for its destruction.[xviii] It was probably seen by the troops though as their right after putting their lives on the line and fighting hard – with alcohol widely seen as one of the spoils of war. Looting of alcohol was a common practice in battles, and at times, the Americans even looted their own rum. A month before the Battle of Trenton, for instance, the Brits and Hessians planned to attack Fort Lee. Many of the soldiers, however, having heard in advance of the pending attack, thought it was a good opportunity to break into the fort’s stores and begin drinking the rum. The British arrived to find the fort nearly empty, with most hiding in the forest nearby, some passed out from drunkenness, and those who remained in the fort also mostly drunk.[xix] The British took the fort easily.

Drunkenness, indeed, was a persistent problem in the Continental Army, and at times it was treated as a more serious offense than desertion. In Washington’s General Orders of July 25, 1776, a soldier named Henry Davis, who had been tried for desertion, was to receive 20 lashes, while Patrick Lyons, who was accused of “Drunkenness and sleeping on his post,” was to receive 30 lashes.[xx] But even as the Continental Army harshly punished drunkenness, it also considered rum as an important part of the soldiers’ daily provisions, and sometimes used it as an incentive to recruit men to perform difficult tasks. During the New York campaign in summer 1776, for example, General Nathanael Greene enticed men to help fortify Cobble Hill in Brooklyn by promising extra rum. “The works on Cobble Hill being greatly retarded for want of men to lay turf,” Greene wrote, “all those in Colonel Hitchcock’s and Colonel Little’s regiments, that understand that business, are desired to voluntarily turn out every day, and they shall be excused from all other duty, and allowed one half a pint of rum a day.”[xxi]

It was also understood, however, that excessive drinking adversely impacted the revolutionary cause and on occasion it was blamed for patriot defeats on the battlefield, for instance at the Battle of Germantown on October 4, 1777. Despite fighting fiercely for five hours, the Americans failed to capture the camp and the British pushed the patriots back to their original positions, with Washington’s casualties numbering 152 killed, 521 wounded, and approximately 400 captured. The Brits fared much better, with 70 lost lives and 451 wounded. Adam Stephen, who had just been promoted to the rank of Major General earlier that year, would bear the brunt of criticism for losing the battle, with alcohol seen as having impaired his decision-making abilities. Stephen was known for his intemperance and apparently was quite drunk during the fighting. He was subsequently court-martialled and found guilty of “unofficerlike behavior, in the retreat from Germantown, owing to inattention, or want of judgement.” The court martial also found that “he has been frequently intoxicated since in the service,”[xxii] and for these transgressions he was stripped of his command and dismissed, making him the only general discharged from the Continental Army during the course of the war.[xxiii]

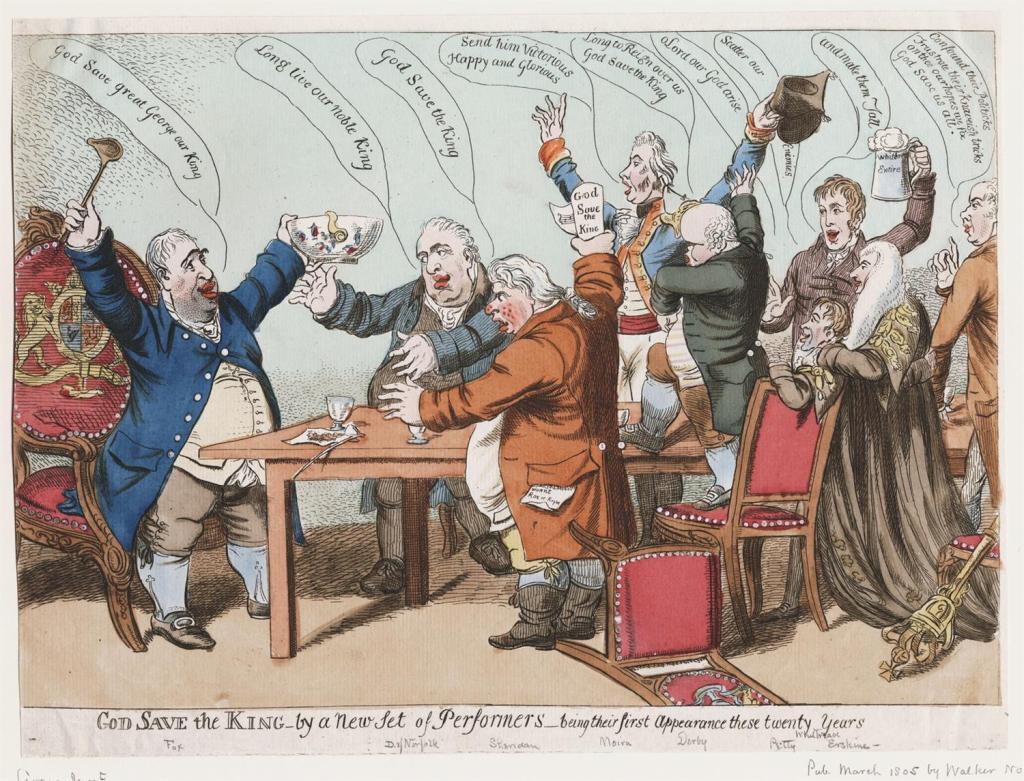

The delicate balance that the army tried to find in its approach toward alcohol – on one hand tolerating and even encouraging limited alcohol use, but also punishing excessive drinking – was reflective more broadly of the equilibrium that society at large tried to establish with booze. It often seemed, however, that this was a losing battle, and following the revolution, America was destined to become a “nation of drunkards,” as a temperance group called the Greene and Delaware Moral Society warned in the early 19th century. Other temperance groups sprouted up in the early republic including the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League, warning that excessive drinking in America was “too obvious not to be noticed” and that it was spreading “wider and wider” in the new nation, “like the plague.” George Washington decried excessive drinking as “the ruin of half the workmen in this Country,” while John Adams asked, “is it not mortifying … that we, Americans, should exceed all other … people in the world in this degrading, beastly vice?”[xxiv]

This vice would continue to shape early American history in important ways, particularly when an alcohol-related insurrection took hold in the early republic during the presidency of George Washington. The heavily indebted federal government decided in 1791 to impose an excise tax on domestically produced distilled spirits, disproportionately impacting farmers of the western frontier who manufactured whiskey and often used it as currency in an informal barter economy in the backcountry. Angered by what they saw as an unfair tax imposed by coastal elites, these farmers launched an insurrection that employed many of the violent tactics that had been used decades earlier in resisting taxes imposed by England, including tar-and-featherings.

Reaching a crescendo in 1794, the Whiskey Rebellion underlined the inescapable reality that alcohol and vice would continue to play an important role in shaping the new nation and raised questions of the limits of government authority, as well as what sorts of protest would be considered legitimate in a democratic republic. Into the 19th century, alcohol would continue to shape the nation’s development in ways both obvious and subtle, even providing some inspiration for the national anthem. “The Star Spangled Banner,” written by Francis Scott Key following 25 hours of British bombardment of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry during the War of 1812, was set to the tune of a popular drinking song called “To Anacreon in Heaven,” an ode to an ancient Greek poet renowned for his erotic poems. While perhaps it is fitting that the new nation, founded by a revolution brought on to some degree by colonists’ love of alcohol, would adopt a national anthem adapted from a drinking song, it also recalls that vice – for better or worse – plays as much a role in the national story as virtue.

Sources:

[i] Massachusetts Gazette and Boston News-Letter, Boston, no. 3268. May 22, 1766

[ii] David Hackett Fischer. Paul Revere’s Ride. Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 193

[iii] “General Orders, 18 April 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11097.

[iv] Rebecca Rupp. “Rum: The Spirit That Fueled a Revolution”. National Geographic. April 10, 2015. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/rum-the-spirit-that-fueled-a-revolution

[v] “The Sugar Act of 1764”. American History Central. https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/sugar-act/

[vi] Samuel Adams. “Instructions to Boston’s Representatives”. May 28, 1764. https://www.revolutionary-war-and-beyond.com/instructions-to-bostons-representatives-may-28-1764.html

[vii] “Seizure of Hancock’s Sloop, 1768–1769,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0021. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782–1804; Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, edited by L.H. Butterfield. Harvard University Press, 1961, pp. 305-306.]

[viii] Boston News-Letter, 16 June 1768

[ix] Deposition of Harrison, 11 June 1768, Treas. 1:465, fol. 74, National Archives of the United Kingdom

[x] Stacy Schiff. The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams. Little, Brown, 2022, p. 150

[xi] Wren, Christopher S. Those Turbulent Sons of Freedom: Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys and the American Revolution. Simon & Schuster, 2018, p. 26

[xii] “The Battle of Trenton”. American Revolutionary War Battles for 1776 https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1776/battle-of-trenton/

[xiii] Edward G. Lengel. General George Washington: A Military Life. Random House, 2005, p. 186

[xiv] David McCullough. 1776. Simon & Schuster, 2006, p. 282

[xv] The Detail and Conduct of the American War, under Generals Gage, Howe, Burgoyne, and Vice Admiral Lord Howe, 3rd ed. War College Series, 1780, p. 40

[xvi] McCullough, David. 1776. Simon & Schuster, 2006, p. 282

[xvii] Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 257

[xviii] Ibid., p. 256

[xix] Ibid., pp. 124-125

[xx] “General Orders, 25 July 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0333. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 5, 16 June 1776 – 12 August 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 457–458.]

[xxi] Johnston, Henry Phelps. The Campaign of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn. Long Island Historical Society, 1878, p. 86

[xxii] Michael C. Harris. Germantown: A Military History of the Battle for Philadelphia, October 4, 1777. Savas Beatie, 2020, p. 445

[xxiii] Stephen R. Taaffe. Washington’s Revolutionary War Generals. University of Oklahoma Press, 2019, p. 123

[xxiv] W.J. Rorabaugh. The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. Oxford University Press, 1981, pp. 5-6

Bio:

Nathaniel Parry is an American living in Denmark who has written or edited several books, including the recently published Samuel Adams and the Vagabond Henry Tufts: Virtue Meets Vice in the Revolutionary Era. His work has appeared in outlets such as Consortium News, In These Times, Common Dreams, Global Research, Truthout, and Lessons from History. Since 2008, he has worked at the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security Cooperation in Europe, where he is currently head of communications.