Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Michael Aubrecht

In 1777 Thomas Jefferson and a committee of revisors came to the City of Fredericksburg for the purpose of revising several Virginia statutes. This led to Jefferson drafting the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

When Jefferson and his comrades arrived in Fredericksburg they were met with a town bristling with military activity. Troops were drilling in the public square and filled the crowded streets, buildings and shops. Awaiting travel orders were the men of the Second Virginia and the Seventh Virginia, ordered here on January 9 for a rendezvous just prior to marching to join General Washington at the front. By the time Jefferson arrived in Fredericksburg, sixty of the more than two hundred battles and skirmishes of the war had already taken place.

On January 12, the very day before Jefferson and the committee began their work, General Hugh Mercer died from bayonet wounds suffered nine days earlier at the Battle of Princeton. Mercer’s apothecary shop stood one block away from where the committee met. Today, Mercer’s statue rises several yards from the Religious Freedom Monument memorializing Jefferson’s bill.

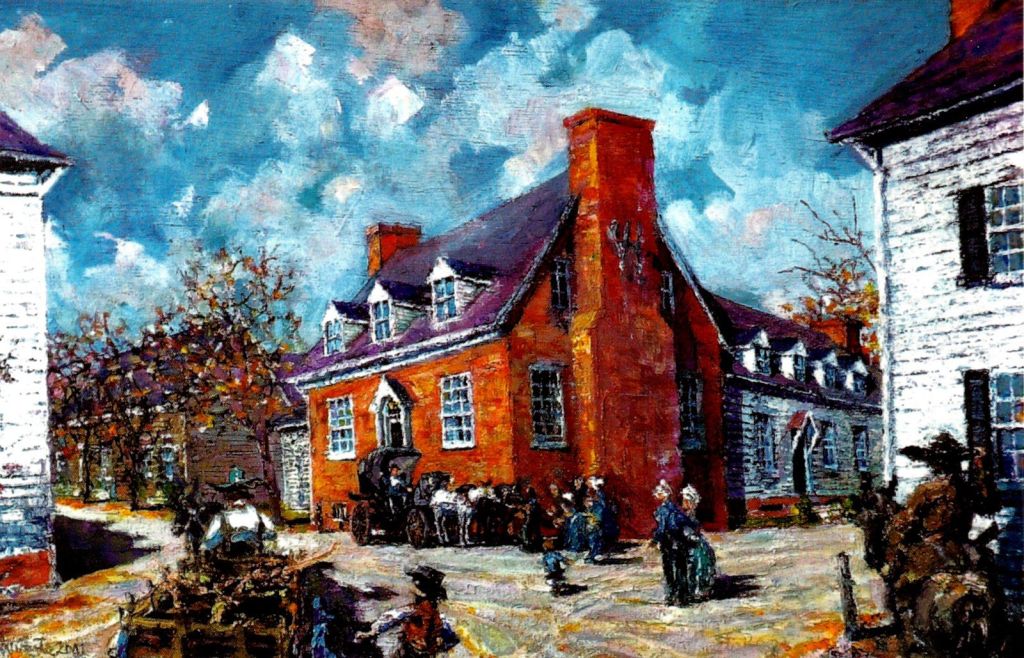

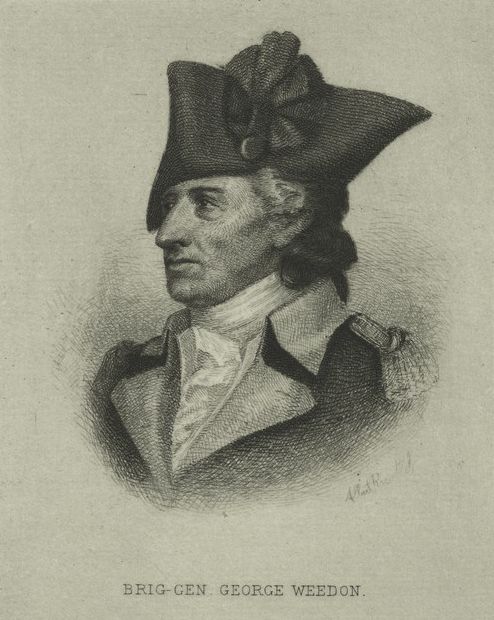

Jefferson and the revisors stayed at a popular tavern in town that was originally named for George Weedon, a local proprietor who fought in the French and Indian War and was later named a brigadier general in the Revolutionary War. A number of highly influential patrons, including George Washington made the tavern a regular stop. Many ledgers in Washington’s journals during the early 1770s listed dining with political dignitaries at Weedon’s Tavern. Playing cards was another favorite pastime at the inn. It is said that as a frequent loser, Washington complained that the Fredericksburg locals were too smart for him.

When the war approached, Weedon took a lieutenant colonel’s commission in the Third Virginia Regiment. He eventually leased the tavern to William Smith in March 1776 to join the militia full time. Smith planned to continue the inn’s service for the duration of the war. Weedon was promoted to the rank of full colonel, and the Third Virginia was soon ordered to join the Continental Army in New York City. He remained with Washington’s army and fought in several major battles. The regiment would eventually see action in the New York Campaign, the Battles of Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown and Monmouth and the Siege of Charleston. When General Benedict Arnold and General William Phillips threatened Virginia in 1781, Weedon organized a battalion of local militia to engage the traitor.

Jefferson remained a vital contact of Weedon’s and supported him during the war. On January 12, 1781, he wrote a letter to Weedon to let him know that more troops were on the way.

Richmond Jany. 12. 1781

Sir

Hearing of 744 Militia from Rockbridge and Augusta and Rockingham

on the road through Albemarle, I have sent orders to meet and turn them

down to Fredericksburg, where they will expect your orders: They are

commanded by Colo. Sampson Mathews. You will [be pleased] to

observe that as all these were to be rifle Men [sic] they were to bring their

own field Officers.

Baron Steuben has sent Colo. Loyauté the bearer of this to me, and

proposed that we should avail ourselves of his Services as an Artillerist for

the protection of Fredericksburg. As this matter is entirely in your hands, I

beg leave to refer him to you altogether. He is desirous of carrying thither

some brass 24. ℔ers from New Castle. They are without Carriages and

of course if mounted on batteries would be in extreme danger of being

taken. I had moreover ordered them to the forks of James River as a place

of safety. Nevertheless should they be absolutely necessary for you, you

will take them, for which this will be your Warrant.

T.J.

A few weeks later, Jefferson once again wrote to Weedon to apologize for being unable to send supplies.

Richmond Jan. 21. 1781

Sir

I am very sorry we shall not be able to furnish you with a supply of lead

until we receive some for which we have sent up the river. The Southern

army has been entirely furnished from hence. Five tons were sent to the

Northern army last fall. This had reduced our stock very low; and of what

was left, one third was destroyed by the enemy. There remains on hand but a

small parcel which is now making up at the laboratory. Should however the

enemy’s movements indicate an intention of visiting you, we will send you

what we have, which I think may be done in time to supply the expenditure

of what you have. The money press has not yet got to work. As soon as it

does I shall be very glad to have money furnished for the purpose of enlisting

men, which I consider as a very important one. I suppose it is impossible for

you to engage them without the ready money. The bounty is 2000 dollars

which should certainly be paid on demand. My last intelligence of the

enemy was that their troops were on shore in the Isle of Wight, and their

shipping at Newport’s news and Hampton road.

I am with great respect Sir your most obedt. servt.,

Th: Jefferson

Ten days later, Jefferson wrote Weedon again, as he was able to procure supplies in Fredericksburg.

Richmond Jan. 31. 1781.

Sir

I am glad that the Commissioners of the provision law in your neighborhood

have agreed to lend their aid in furnishing you with provisions. They are

certainly justifiable as that law has been reenacted by the assembly. As soon

as a force began to collect at Fredericksburg I directed the Commissary Brown

(who is authorized by the law to instruct the Commissioners in what is to be

expected from them) to take immediate measures for procuring subsistence for

those forces either by sending a deputy or applying to the Commissioners.

Your arrangements for the defence [sic] of Potowmac [sic] and

Rappahanoc [sic] appear to have been judicious. Baron Steuben coming

here soon after the receipt of your letter I referred to him to do in that what

he should think best, as it is my wish to furnish what force is requisite for

our defence [sic] as far as I am enabled, but to leave to the commanding

officers solely the direction of that force. I make no doubt he has written to

you on that subject.

I am with great respect Sir your most obedt. humble servt.,

Th: Jefferson

After the Continental Army defeated General Cornwallis’s forces at Yorktown, a Great Peace Ball was hosted by Weedon at his tavern. On November 11, 1781, American and French officers, politicians, wealthy planters and domestic and foreign dignitaries attended the ball. General George Washington attended, as did the Marquis de Lafayette, who arrived arm and arm with Washington’s mother, a local Fredericksburg resident.

Weedon remained the inn’s proprietor for a while longer, as his efforts were more focused as a member of the local council and a church vestryman. He retired from innkeeping to become the mayor of Fredericksburg in 1785.

Michael Aubrecht is the author of Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom: Faith & Liberty in Fredericksburg.

Pingback: New Article | The NAKED HISTORIAN