October of 1776 was a scary time during the Revolutionary War. George Washington’s army had suffered major defeats in August and lost the city of New York to the British Army. By October many of Washington’s men had fallen back towards White Plains, New York where they prepared to defend themselves. Morale was plummeting among the Continental Army and it seemed the Americans would lose the entire war before the end of the year.

It was around this time that some believe the story of the Headless Horseman had its origins. The Headless Horseman is a legendary ghost who first made his appearance in Washington Irving’s classic “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” which was originally published in 1820. The story is set in the early years of the republic in a small town on the Hudson River.

While this is a fictional story, it has some basis in fact. The village of Sleepy Hollow is a real place in Westchester County in New York, less than ten miles from White Plains, New York. The ghost known as the Headless Horseman that haunted this village is referred to by Irving in the story as “the ghost of a Hessian trooper, whose head had been carried away by a cannonball, in some nameless battle during the Revolutionary War.”

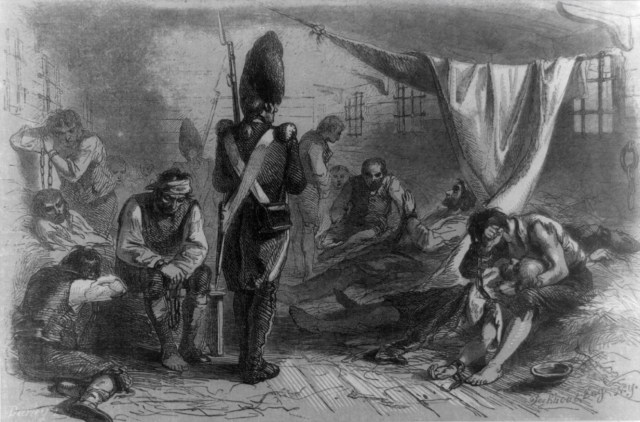

A Hessian soldier made a natural choice for this fearsome ghost. Hessians were greatly feared by Americans during the Revolutionary War. These German soldiers were sent by the thousands to America to reinforce the British. Hessians got their name as many of these soldiers were from Hesse-Kassel in Germany. These foreign speaking mercenaries were viewed as bloodthirsty killers and easily vilified. They were renowned as fearsome fighters and there were stories that they showed no quarter to retreating American troops at the Battle of Long Island, including nailing American riflemen to trees with their bayonets. However, some of these Hessian soldiers were probably misunderstood. Many of them had been pressed into service and were forced to fight for their princes. Many Hessians even preferred life in America and thousands decided to desert and settle in America at the end of the war rather than return to Germany.

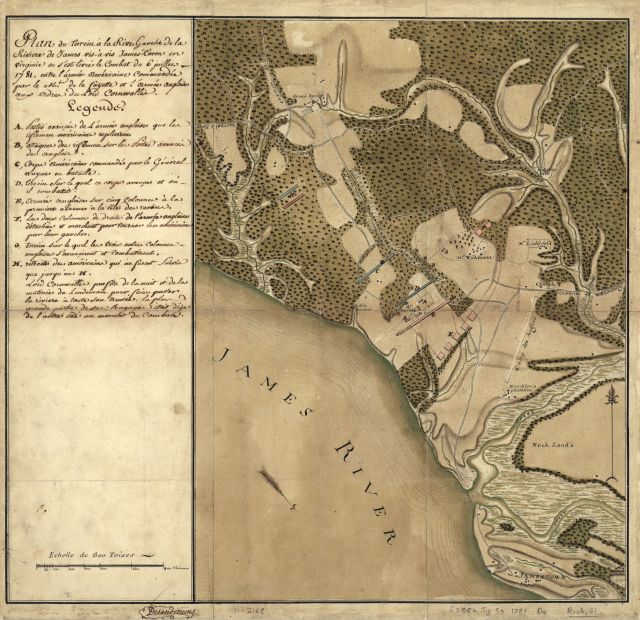

The Hessian that provided the inspiration for the Headless Horseman may have been killed during the Battle of White Plains on October 28, 1776. Washington Irving even mentions this particular battle in his tale when he recounts a small anecdote of an “old gentleman . . . who, in the battle of Whiteplains, being an excellent master of defence, parried a musket ball with a small sword.” During this battle Hessian troops played a large role.

Some of these Hessian troops, commanded by Colonel Johann Rall, led a flanking assault on the American troops and pushed the entire American force back. More than 400 British, Hessian, and American soldiers were dead or wounded at the end of the day and although the Americans fought bravely, Hessian and British troops commanded the battlefield.

Perhaps the ghost of the Headless Horseman was the spirit of one of the many Hessian soldiers killed during the Battle of White Plains. Another possibility is one of the Hessians killed in the skirmishing that occurred in the days that followed. Major General William Heath of the American army remembered a particular skirmish that occurred a few days later on November 1, 1776 when “a shot from the American cannon at this place took off the head of a Hessian artilleryman. They also left one of the artillery horses dead on the field.”

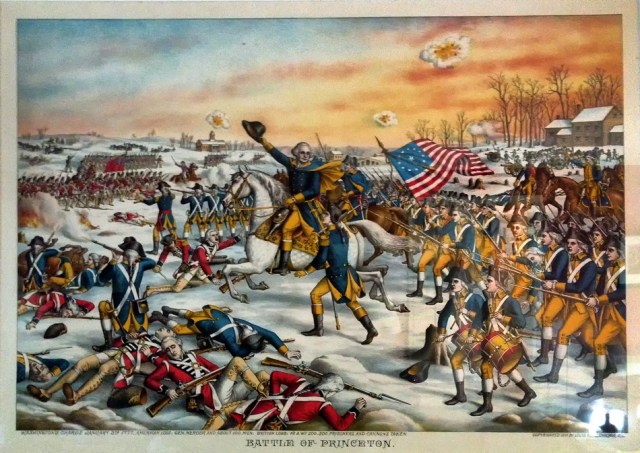

Regardless of the true origins of this ghost, the Hessians’ victory at White Plains was short lived. Colonel Rall and his brigade of Hessians would be surprised and captured by George Washington’s men at the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776, which would prove to be a major turning point in the Revolutionary War.

While the Battle of White Plains has been all but forgotten, the story of the Headless Horseman has become a touchstone which still connects us with this battle and the Revolutionary War in general. And just like we like to find where these battles took place and walk the hallowed ground, so too does the Headless Horseman. Irving writes that while the body of the Hessian lies “buried in the churchyard, the ghost rides forth to the scene of battle in nightly quest of his head.” I urge you to follow in his footsteps and check out Battle Hill Park next time you are in White Plains, New York and the historic environs of Sleepy Hollow nearby.