There has been a lot of discussion recently (and over the past few decades) on Washington, D.C.’s ability to self rule and representation. Washington (the city within the District of Columbia) is one of a kind Federal District created explicitly by the Constitution. The creation and future authority of the District was very purposeful by the founders. The authority to create a federal district was established in the U.S. Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 states:

“To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States.”

This clause explicitly grants Congress the power to establish a federal district and to exercise complete legislative control over it. The reasoning behind this provision was to prevent any single state from having undue influence over the national government. The framers of the Constitution wanted to ensure that the federal government had an autonomous and secure location from which to operate, free from state-level political pressures.

The need of a capital under Congressional control was highlighted in the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783. On June 20 1783 when a group of nearly 400 soldiers from the Continental Army, frustrated over unpaid wages and poor treatment, marched to Philadelphia and surrounded the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall), where the Congress was meeting.

The soldiers demanded immediate payment and redress for their grievances, creating a volatile situation. The Pennsylvania government, sympathetic to the mutineers, failed to act decisively to protect Congress. As a result, Congress fled to Princeton, New Jersey, marking the first and only time the U.S. government was forced to relocate due to domestic unrest.

The mutiny underscored the weakness of the Articles of Confederation, particularly the lack of a control Congress had over its on own capital. Also, without a standing national army to maintain order, Congress relied on the state militias. Which proved to fail them in 1783.

Selecting the location for the new nation’s capital became a contentious issue. Different regions of the country had competing interests. Northern states, particularly those with economic centers like Philadelphia and New York, wanted the capital in their territory, while Southern states, particularly Virginia and Maryland, wanted it further south.

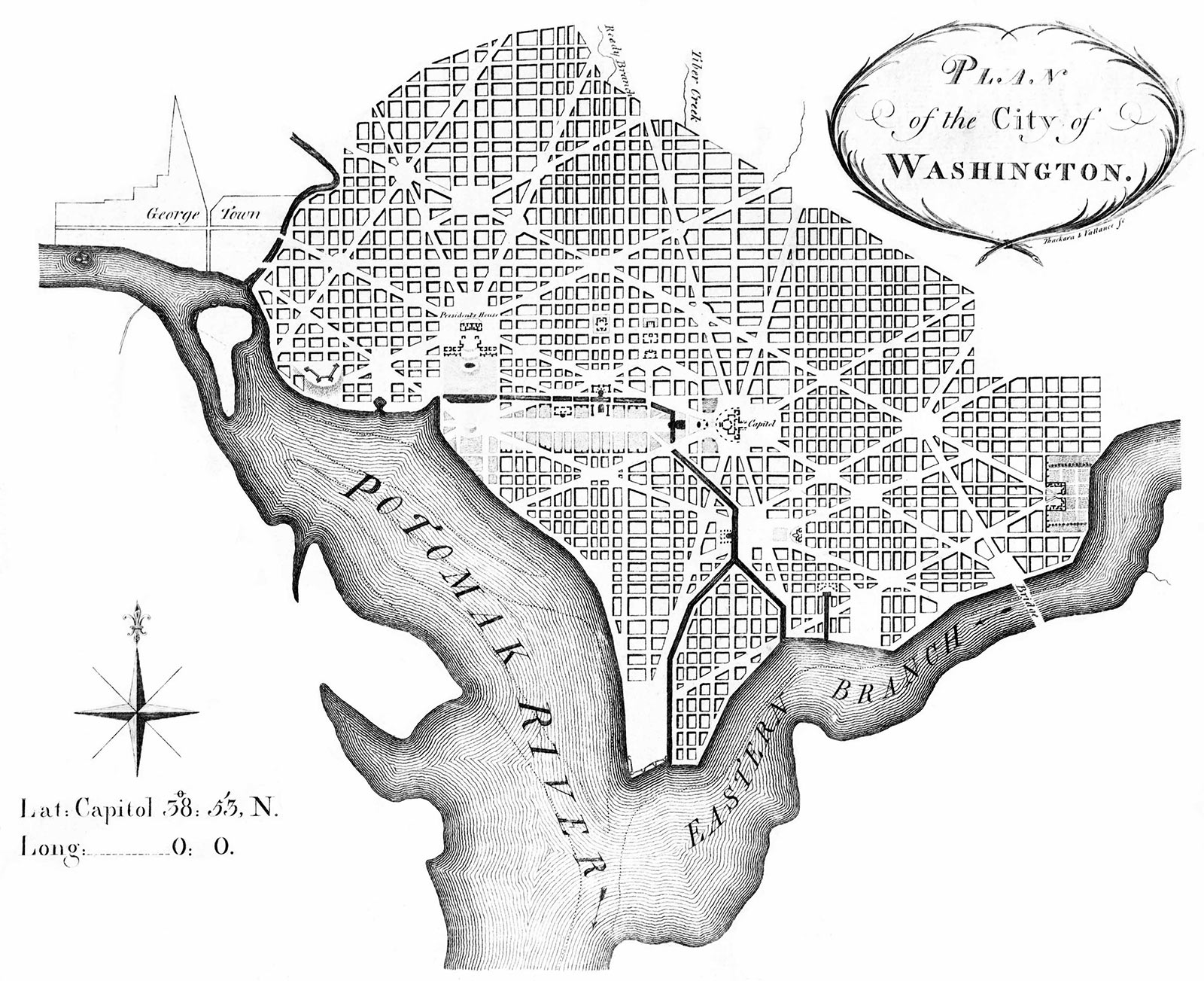

The final compromise, known as the Residence Act of 1790, resulted from negotiations between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, brokered by President George Washington. As part of the deal, the federal government assumed the war debts of the states, and in exchange, the capital would be located along the Potomac River, on land donated by Virginia and Maryland (near George Washington’s own Mount Vernon).

Washington, D.C., was officially established in 1791, and Congress first convened there in 1800. The land included portions of Maryland and Virginia, although the Virginia section (Arlington and Alexandria) was retroceded to the state in 1846.

One of the primary reasons for creating Washington, D.C. as a federal district was to ensure neutrality. If the capital were located within a state, that state might wield excessive influence over the Federal government. The founders sought to prevent any potential conflicts of interest and ensure no state could claim privileged status or exert undue pressure on national affairs.

As a federal district, Washington, D.C., is directly governed by Congress. Unlike states, which have their own constitutions and legislative powers, the district’s governance structure is determined entirely by federal law. Over the years, this has led to ongoing debates about the representation and rights of D.C. residents. Today the city has an elected Mayor and City Council that manages the city’s affairs, but this authority is granted solely at the will of Congress. The debate over home rule and representation goes on, but the founding of a Federal District is rooted in a historic lesson learned by the early Congress.