On this date in history…

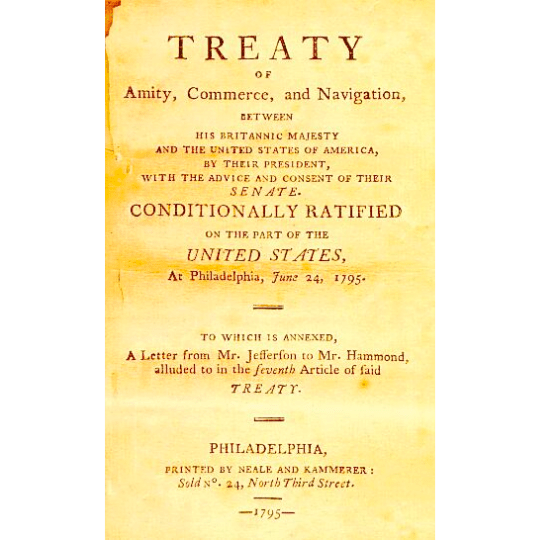

On November 19, 1794, John Jay, representing George Washington’s administration, affixed his signature to a document bearing his name in history. The Jay Treaty. Although the official name of the pact was “The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America.”

The treaty’s aim was to resolve outstanding issues from the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War and facilitate economic trade. Although some of the clauses were not fulfilled completely and another war, the War of 1812, erupted because of it, the treaty did serve a purpose. The agreement ushered in a decade of trade between the two countries and gave the fledgling nation a chance to gain footing, a major concern for George Washington, as first president. The treaty also cemented the promise that Great Britain would vacate the forts in the Northwest Territory and agreed to arbitration on the boundary between Canada and the United States and the pre-American Revolutionary War debt.

Yet, the treaty was divisive. Even Jay remarked that he could find his way in the dead of night by the illumination of his own effigy. The treaty angered the French as that country was amid its revolutionary throes, and bitterly divided the nation. Out of it came the separation into two political parties, the Federalists, who supported the treaty, and the Democratic-Republicans who stood opposed to it.

The treaty was ratified by the Senate on June 24, 1795, with an exact two-thirds majority, 20 to 10 along with being passed by William Pitt the Younger, prime minister of Great Britain and his government, and took effect on February 29, 1796.

Historian Joseph Ellis wrote that the Jay Treaty was “a shrewd bargain for the United States” and “a precocious preview of the Monroe Doctrine.” As one of Washington’s most fervent wishes, the treaty “postponed war with England until America was economically and politically more capable of fighting one.”

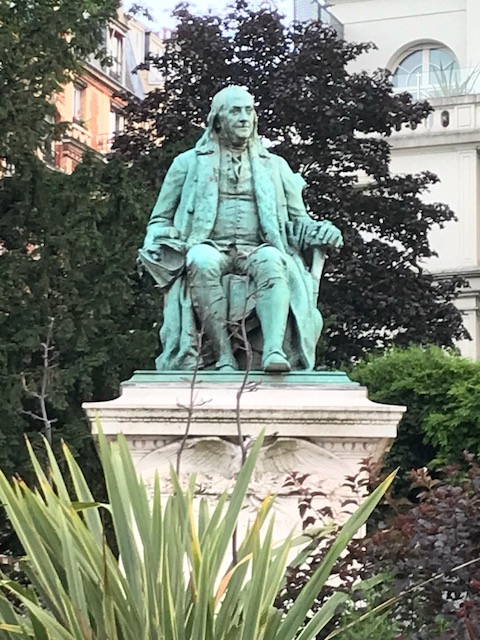

So, vacation time rolls around again and this year my family and I had an opportunity to travel to Paris, France for a few days. Riding into the city from Charles de Gaulle Airport, our taxi driver, by chance, took us past an old, green-corroded bronze statue, set in the middle of a little flowered square. From my vantage, I could only see the bottom portion of the statue; what appeared to be the lower portion of a man in buckled shoes, seated in a wooden chair, atop a marble pedestal. My wife happened to be in the right spot in the vehicle as we quickly drove by. “Looks like Benjamin Franklin, I think.” she said, and with those words, she sent me on a journey to find that statue again and, hopefully, other sites in Paris associated with Mr. Franklin.

So, vacation time rolls around again and this year my family and I had an opportunity to travel to Paris, France for a few days. Riding into the city from Charles de Gaulle Airport, our taxi driver, by chance, took us past an old, green-corroded bronze statue, set in the middle of a little flowered square. From my vantage, I could only see the bottom portion of the statue; what appeared to be the lower portion of a man in buckled shoes, seated in a wooden chair, atop a marble pedestal. My wife happened to be in the right spot in the vehicle as we quickly drove by. “Looks like Benjamin Franklin, I think.” she said, and with those words, she sent me on a journey to find that statue again and, hopefully, other sites in Paris associated with Mr. Franklin.