Kentuckians knew 1777 as the “Bloody Sevens” due to the severity and frequency of Native American attacks. Those raids were difficult in the spring, but only intensified after June, when Henry Hamilton, a Detroit-based lieutenant governor of Quebec, executed his orders to actively promote and support Native American offensives across the Ohio River. In particular, war parties from the Ohio and Great Lakes Indian nations allied with Britain crossed the Ohio and struck the region’s three largest towns: Harrodsburg, Boonesborough, and St. Asaph’s/Logan’s Fort. Of the three, the last was the smallest by far, and yet it was the scene of some of the year’s most dramatic moments.

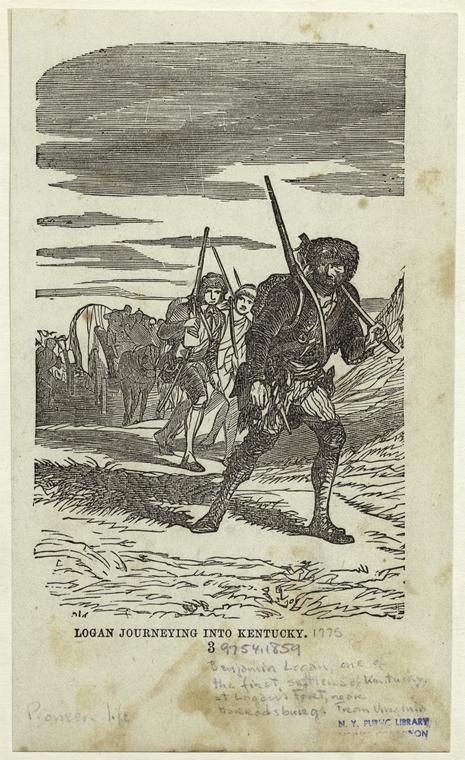

In the spring of 1775, Benjamin Logan led a surveying party into Kentucky and established a “town” of sorts—mostly surveyor’s huts—that they dubbed St. Asaph’s. For his part, Logan built a log cabin and planted a corn crop that later established his land claim. Logan’s group did not remain long as Kentucky was already under attack, but he and several others, including his family, eventually returned in March 1776.[1] A raid on Boonesborough that summer prompted the St. Asaph’s residents to begin fortifying their town. Logan’s family left for the additional safety of Boonesborough, but he remained behind with several enslaved people to continue working on the fort.

Fortified towns were typically established by building two lines of cabins in parallel lines with their fronts face one another. Windows were limited to the front and perhaps the sides, but the rear wall was solid with narrow firing slits. Gaps in between cabins were then closed by digging a trench and standing cut posts in them upright, then filling in the trench and creating a wall. It was a fast means of quickly building a fort. More robust defenses would include blockhouses at the corners with overhanging rooms on a second story enabling defenders to fire down and along walls. There would be a substantial gate on one side and then perhaps a sally port or two along the walls or in a corner blockhouse. The common area between the rows of cabins would often have common buildings and facilities, such as a smithy, herb gardens, a powder magazine, etc. Several buildings, ranging from cabins to storehouses and horse stalls, might remain outside the walls. Residents of the community would then retreat into town when concerned about attack. Logan moved his family back to the fortifying town in February.[2] Logan took the additional step of digging a trench to a nearby spring to create a secure water supply. He then covered it and it was sometimes referred to as a tunnel, even though it was not completely underground.[3] The fort at St. Asaph’s, now more widely known as Logan’s Fort, was completed just in time.