On August 27, 1776, in Brooklyn, New York, a small contingent of Maryland soldiers showed the world what valor and patriotism looked like. During one of the largest and bloodiest battles of the Revolutionary War, the actions of these brave soldiers would earn them the venerated name of the Maryland 400.

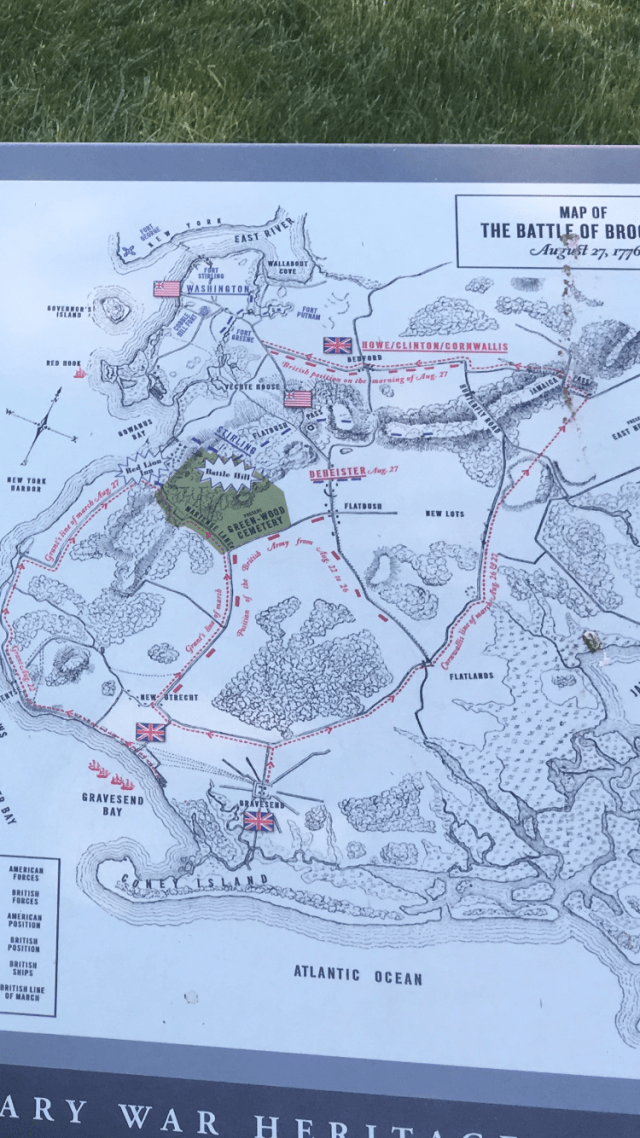

At the Battle of Long Island, the American Army was strung out in a long line across modern day Brooklyn facing south, with Washington and his headquarters located at Brooklyn Heights. However, Washington and the Americans had failed to guard the extreme left flank of the American line. As a result, British General William Howe divided his army in two, attacked the American main line head on to hold them in position, while British Generals Charles Cornwallis and Henry Clinton marched around the American flank and attacked from the east.

As the battle played out during the day of the 27th, the men of the 1st Maryland Regiment, under the temporary command of Major Mordeci Gist, were positioned on the right flank of the American Army, near present day Green-Wood Cemetery. Gist’s men were in General William Alexander’s (Lord Stirling’s) brigade. Stirling’s men were engaged heavily that morning as they fought the diversionary force in their front. The battle raged on what is today known as Battle Hill, and the Americans felt confident they were winning the day’s battle.

Late in the morning though, the Marylanders began to hear the sounds of musketry and cannon fire coming in from their left and rear. They soon realized that the American position had been flanked and that they would soon be totally surrounded and annihilated. They were immediately ordered to retreat. They fell back to the banks of Gowanus Creek, which had to be crossed to reach the relative safety of Brooklyn Heights. The bridge across the Creek had been burnt and the Americans would have to swim across to escape. As the Americans stood looking at the Creek, Cornwallis and his Light Infantry appeared and began to fire on the retreating American soldiers. Cornwallis sent some of his men to occupy an old stone house (the Vechte-Cortelyou House) near the creek and fire into the panicking men. At this critical juncture, with the whole of Stirling’s brigade about to be crushed, Stirling ordered Gist’s men to charge the British line.

It was an impossible task, and Gist and his soldiers probably knew it too. Gist, with less than 400 men was to assault the vanguard of an entire British division, numbering at least 2,000 men with artillery. But, Stirling needed something to allow his division to escape into Brooklyn Heights. He himself would stay and fight with this rearguard. The Marylanders, in their first real battle, didn’t hesitate at all. Closing up their ranks, the Old Line pushed forward into the hailstorm of lead numerous times. As musket balls thinned their lines, the Marylanders would fall back, reform and strike again. On a hill at Brooklyn Heights, Washington watched the action in his spyglass. “Good God! What brave fellows I must this day lose!” he exclaimed as he witnessed the sacrifice of some of his best soldiers.

The brash and bold attacks had the exact effect Stirling needed. The British, temporarily stunned by the attacks, paused to fight this small contingent of soldiers. Meanwhile the remainder of Stirling’s men successfully crossed Gowanus Creek and arrived in the main American lines. General Stirling, still fighting from horseback was eventually surrounded and captured by some Hessian soldiers.

After a sixth and final charge by the Maryland troops, Gist’s command had been effectively destroyed. Gist and a handful of his men finally fell back and crossed Gowanus Creek themselves. The Marylanders had helped many American troops escape capture and death, and also caused a diversion that stopped any possible assault on the main American position at Brooklyn Heights. Gist and a few dozen survivors had made it back to the main army, but back on the fields around the Vechte-Cortelyou House 256 Marylanders lay dead or dying. It was one of the highest number of casualties a regiment would lose in the war.

The battle was all but over. It appeared that the 9,000 Americans who were now holed up on Brooklyn Heights would all be captured, but Washington successfully evacuated the entire army over to Manhattan. The war would continue for seven more years and end with independence for America, but that may not have been the case had the Maryland troops not sacrificed themselves for the fellow men, and bought the American Army precious time.

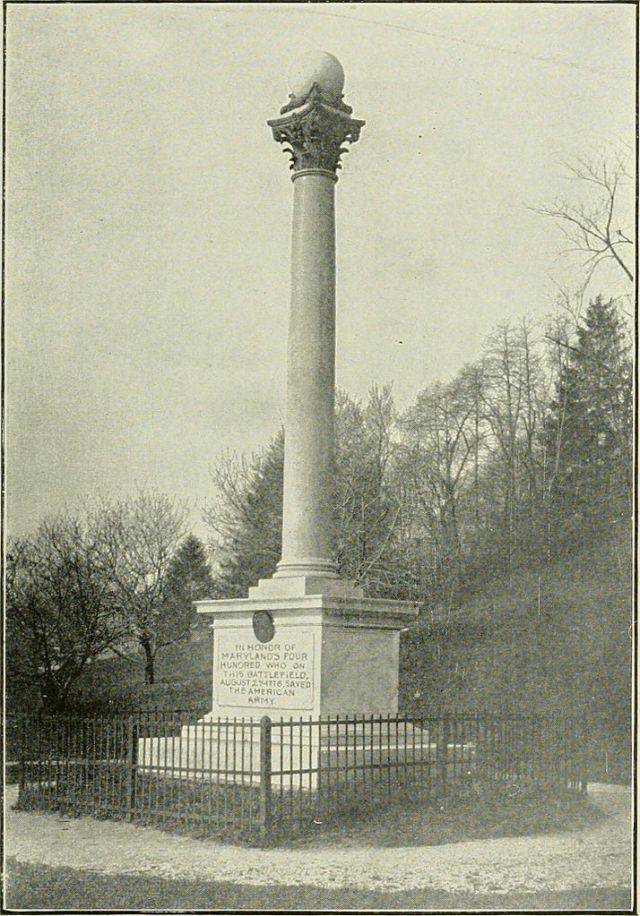

Today, archaeologists are looking for the graves of those who were killed in the assaults at Brooklyn. Hopefully, they will receive a proper resting place, as they are due. Other than a monument located in Prospect Park, it is difficult to find reminders of this important history in modern day Brooklyn. New Yorkers walk throughout the Park Slope neighborhood, unaware of how hallowed the ground is they tread on. This August 27, remember the brave men of the Maryland 400 and the freedom they died for.

Thank you,Mark Maloy for educating us on what real heros sacrificed in fighting for the freedom we all take for granted..It is especially poignant as we see statues and memorials being desecrated all over this country by ignorant persons who have no knowledge or understanding of what it took to create this great country that no other compares to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks to Mark Maloy and the Emerging Revolutionary War Era for this wonderful presentation on the Maryland 400. All the best, Mel Bernstein

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Is the Mercer Legacy Secure? | Emerging Revolutionary War Era

Thank you for making me really understand what my early ancestor, Thomas Wiseman, must have gone through that awful day as he was one of the survivors where he lost his 2 middle fingers on his left hand. But he kept on fighting for our freedom which seems we are losing today. Thomas ended up in SC sick at the Battle of Camden, SC and did not re-enter the War, Bill Wiseman

LikeLike