“To-morrow an oration is to be delivered by Dr. [Joseph] Warren,” Samuel Adams wrote on March 5, 1775, the fifth anniversary of the infamous Boston Massacre. “It was thought best to have an experienced officer in the political field on this occasion, as we may possibly be attacked in our trenches.”

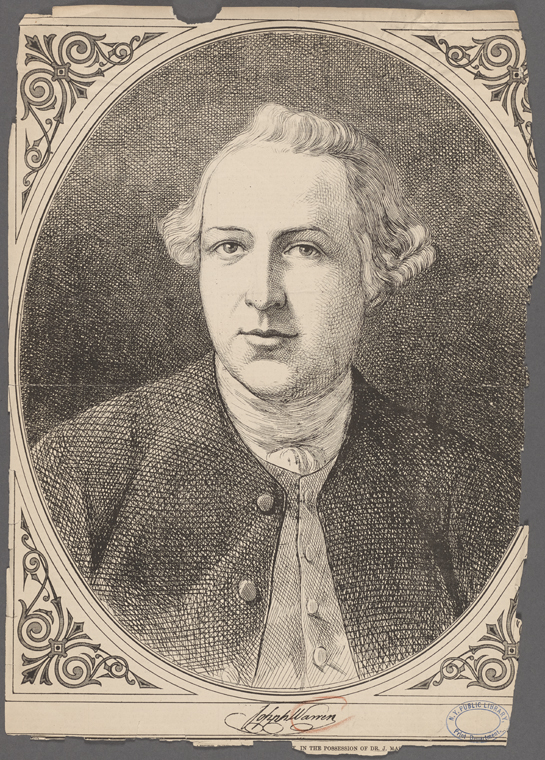

Around every anniversary of the Boston Massacre, the people of the city and surrounding countryside sat to reflect on the events of that frigid March night and the current situation between themselves and their mother country. Chosen to deliver the 1775 commemorative oration, his second time doing so, was one of Boston’s most prominent physicians and chairman of the committee of safety, Dr. Joseph Warren. Because March 5 fell on a Sunday, the event was held the following day.

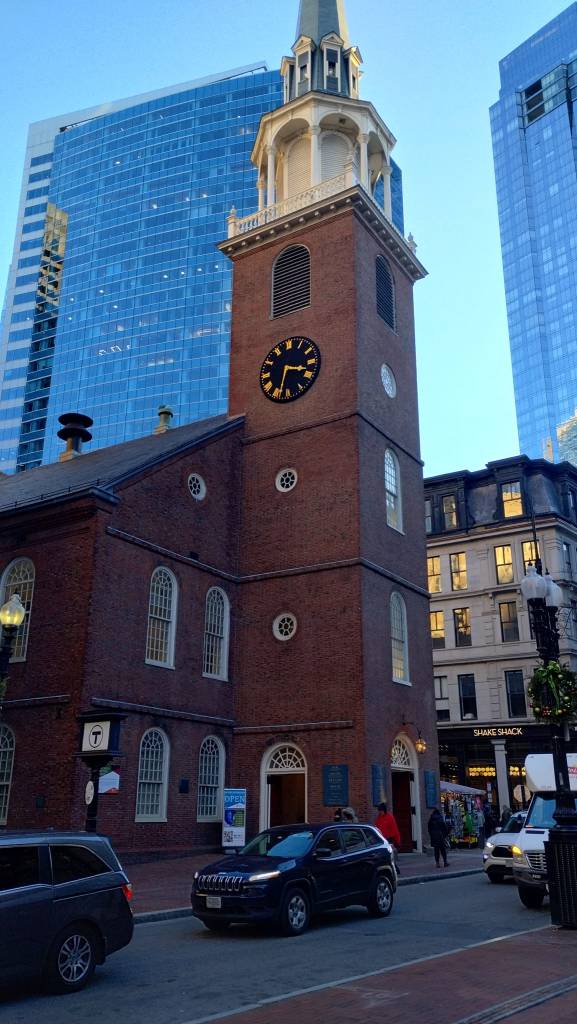

Warren was known to be a passionate and fiery speaker, able to invoke the raw emotion necessary to drive his listeners to action. The political climate surrounding that year’s event was never more incendiary. While no one could have known it at the time, though many anxiously anticipated something coming, the first shots of the Revolutionary War at Lexington and Concord were only a little more than a month in the future. The events on March 6 within the walls of the Old South Meeting House did nothing to ease those anxieties.

Accounts vary on the numbers and makeup of the attendees, but thousands flocked to the commemoration, including a large group of British Army officers garrisoned in the city. The presence of His Majesty’s soldiers was a sure sign that the building would be thick with rigid tension. The sight of the scarlet-coated men seated and standing around the pulpit did not deter the organizers. John Adams showed civility towards the officers, while his cousin Samuel saw an opportunity to enflame sentiments.

Dr. Warren, 33 years old in March 1775, took the stage garbed in a toga, a symbol of the free men of Rome. His oration only touched upon the events five years prior, but the remainder oozed with patriotic fervor and a call to resist Great Britain’s rule until grievances were met. “I mourn over my bleeding country,” Warren lamented. “With them I weep at her distress, and with them deeply resent the many injuries she has received from the hands of cruel and unreasonable men.” As if a premonition of his own demise in battle at Bunker Hill several months later, he declared, “Our liberty must be preserved. It is far dearer than life.” The speech in its entirety can be read here.

Met with some low hisses and sighs of disapproval from the front rows, Warren’s oration was nonetheless received with emotion and the admiration of his fellow colonists. It was not until he stepped down from the pulpit that pandemonium began to ensue. Samuel Adams rose to appoint a speaker for next year’s commemoration. In doing so he also took the opportunity to reinforce the belief that the events on March 5, 1770 were not an accident, but a “Bloody Massacre.” Even Warren had refused to use this rhetoric. In response, the British officers began to jeer, shouting “Fie! Fie!” and “To Shame!” The already uneasy crowd mistook the shouts as “Fire! Fire!” and many began rushing for the windows, scrambling down the outside gutters and walls. As if this was not enough, the 43rd Regiment of Foot, returning from exercise, happened to be marching by with fife and drum. Their presence threw the crowd “into the utmost consternation,” who may have believed another “bloody massacre” was about to unfold.

Cooler heads prevailed, and any serious confrontation was avoided. Had it not been, one officer attested that it “wou’d in all probability have proved fatal to [John] Hancock, Adams, and Warren, and the rest of those Villains, as they were all up in the Pulpit together.”

March 6, 1775, proved to be another example of the swiftly deteriorating climate in Massachusetts. The influence of the “rebel” leaders continued to grow, while the image of a tyrannical monarch and his blood-thirsty soldiers was reinforced. Open hostilities seemed inevitable. Any day could bring bloodshed. As history exited the Old South Meeting House that day, it continued its accelerated journey down the road from Boston and on to Lexington Green.

Read Founding Martyr by Christian Di Spigna for all the details regarding this event and Warren’s life.

LikeLiked by 2 people