Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian Dr Lawrence Howard

Many people have not been taught that slavery was practiced in early America’s northern colonies, later states. Though fewer people were enslaved in the north than in the south, where the plantation economy was highly reliant on enslaved labor, people were also held in bondage in the north. Also not often taught is the contribution such enslaved persons made to the success of America’s Founding, though recent scholarship seeks to amend this. This article explores the 1779 Petition to the New Hampshire Government, written by Prince Whipple – born in Africa in 1750 and purchased by William Whipple of Portsmouth, New Hampshire at a young age. In this petition, twenty black men requested emancipation from slavery. The African American petitioners echoed some of the same political ideas that the delegates to the Second Continental Congress had staked their own lives on just three years earlier in the Declaration of Independence, announcing American political independence from Britain.

After marrying Katherine Moffatt, William Whipple, a wealthy merchant and sea captain, moved into his in-law’s house, a Georgian mansion in Portsmouth, bringing with him household furniture and his enslaved servant, Prince.1 The historical record does not tell us exactly why Prince came to America. He most likely was kidnapped and sold into slavery, though some reports indicate that his wealthy African family may have sent him to Britain’s North American colonies for a quality education, resulting in his enslavement at some point.2 In either case, he was about ten years old when he was purchased by William Whipple, who ensured that Prince received an education and learned to read and write.3

As a New Hampshire delegate to the Second Continental Congress from 1774-1779, William Whipple took Prince with him on his trips to Philadelphia.4 It is reasonable to assume that is was during his time in Philadelphia that Prince learned about the American Patriots’ cause, their demands for freedom, and their informing the King and Parliament of their political separation with the Declaration of Independence.

Whipple fought in the American Revolution as part of the New Hampshire Militia, with some people reporting that he participated in Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River and Battle of Trenton in December of 1776.5 This is unlikely. Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting, “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” includes a black man, often identified as Prince Whipple.6 But neither William Whipple nor Prince Whipple were with Washington’s army at this time. Instead, Prince accompanied William Whipple, then a brigadier general in the First Brigade of the New Hampshire militia, and served as a soldier and manservant.7 They marched with the brigade to Saratoga in 1777, both later participating in the Rhode Island Campaign of 1778.8 Prince Whipple fought for the cause of liberty, which he himself was denied.

Prince married Dinah Chase in 1781 in Portsmouth New Hampshire.9 Also enslaved at the time of their marriage, Chase was freed in 1781. In recognition of Prince’s military service, or perhaps as a wedding gift, William Whipple granted him the rights of a free person in 1781, formally freeing him in 1784.10 Prince died in Portsmouth in 1796, having continued working for the Whipples as a free man.

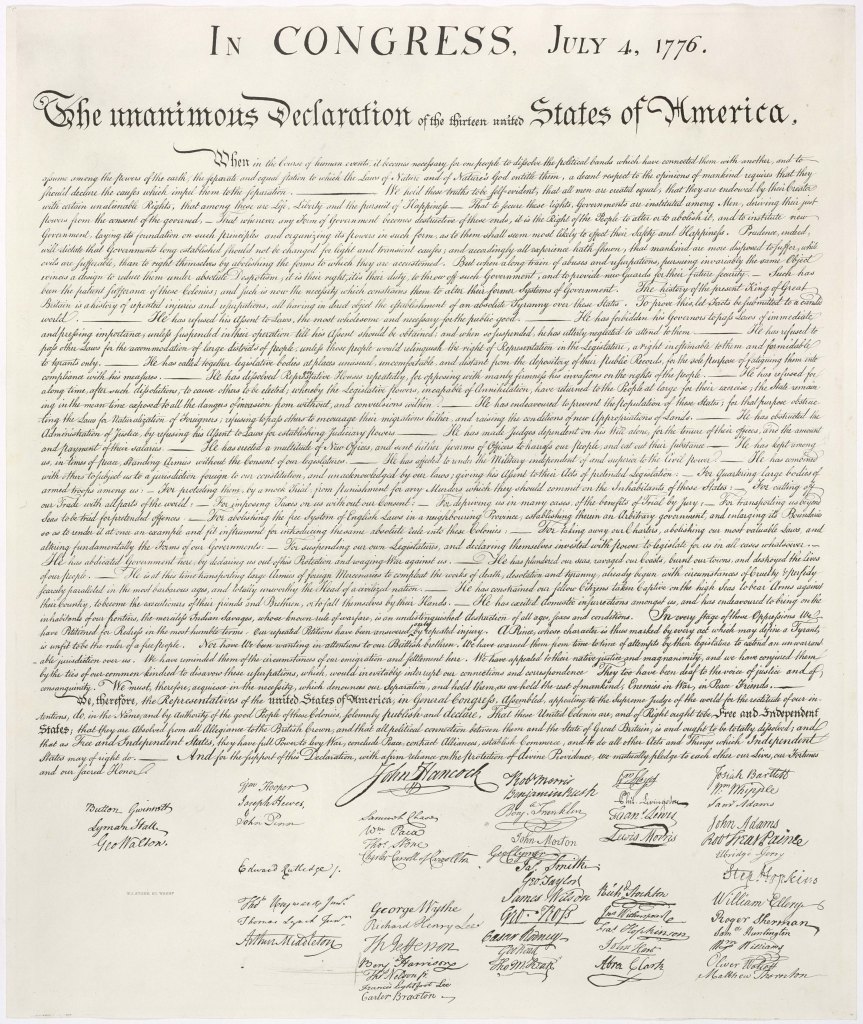

One of the most interesting parts of Prince’s life was when he signed, and likely wrote, a four-page petition to the New Hampshire government on November 12, 1779.11 In this petition, twenty enslaved New Hampshire men requested emancipation from slavery. The signers echoed some of the same political ideas that the delegates to the Second Continental Congress, where William Whipple had served as a delegate, espoused.12 The petitioners wrote to the New Hampshire government asking that they be freed. Their argument was simple, connecting the petition to the same political, religious, and enlightenment ideas that the Founders used when arguing for political separation from Britain. They declared that they had been “forcibly detained in slavery,” even though, echoing the Enlightenment thinking about natural law in the Declaration of Independence, that “the God of Nature gave them [the enslaved] Life and Freedom,” and that “freedom is an inherent right of the human species.”13 They also asserted that New Hampshire should grant them freedom because God gave equality, so the government was “duty bound, strenuously to exert every faculty of their minds to obtain that blessing of freedom [for the African-American petitioner] which they are justly entitled to from the donation of the beneficent Creator.”14

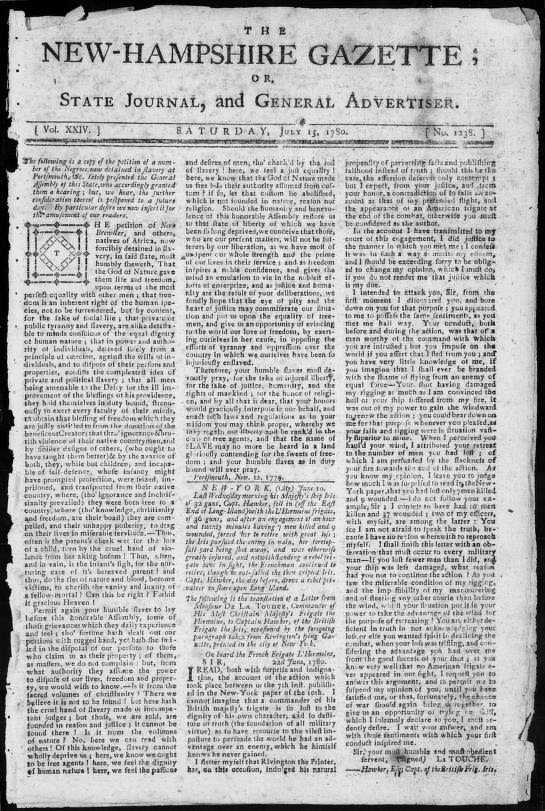

https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83025584/1780-07-15/ed-1/?sp=1.

The petitioners then rejected all possible reasons that they should continue to be enslaved. They asked if slavery was permitted under natural law, answering the question themselves: “No! . . . Here we know that we ought to be free agents! Here we feel the dignity of human nature. Here we feel the passions and desires of men, though checked by the rod of slavery. Here we feel a just equality. Here, we know that the God of Nature made us free!” They concluded their rejection of slavery by declaring that the custom of chattel slavery “be abolished which is not founded in nature, reason nor religion.”15

Prince Whipple and the other petitioners believed that there was no justifiable reason to remain enslaved, asking that, “for the sake of injured liberty…” they be freed. The petitioners asserted that by freeing them, the government would be acting in accordance with the nation’s founding principles because the petitioners would “regain our liberty and be ranked in the class of free agents and that the name of slave may not more be heard in a land gloriously contending for the sweets of freedom.” Only with their freedom, and by extension the freedom of all enslaved, would America itself truly embrace the ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

There is an interesting footnote to this story. The New Hampshire government did not conduct any hearings in 1779. Instead, the House of Representatives chose to publish the text of the petition in the New Hampshire Gazette in July 1780, a move calculated, perhaps, more to ridicule the twenty petitioners than act on the petition. As mentioned above, William Whipple manumitted Prince in 1781. In 1857, the New Hampshire state government implicitly abolished slavery by declaring, “No person, because of decent (sic), should be disqualified from becoming a citizen of the state,” later explicitly endorsing an end to slavery when New Hampshire ratified the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on July 1, 1865.16 On July 7, 2013, New Hampshire’s governor signed into law a bill posthumously emancipating the fourteen African-American petitioners who had not been freed by their enslavers (six were freed during their lifetimes).17 More than 233 years after the petition, the New Hampshire government finally responded to Prince Whipple’s petition and freed the petitioners.

Several weeks after the October 1775 burning of Falmouth, Massachusetts (now Portland, Maine), William Whipple wrote to a friend about how the British destruction of Falmouth was evidence that no American city was safe from a similar fate in which the British would attack the “Liberties & privileges” of Americans, but that the “cruelties of the enemy have so effectually united us [against] the Tyranny of Great Britain.”18 Less than one year later, in the words of the Declaration of Independence, America’s Founders asserted as “self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”19 Enslaved men like Prince Whipple also fought for American independence as soldiers and as Patriots, helping to eventually, albeit slowly, turn the aspirations in the Declaration into reality for all Americans.

Sources:

- Carol Berkin, “William Whipple, 1730-1785,” Signers’ Biographies, National Constitution Center, https://constitutioncenter.org/signers/william-whipple; “5 Generations and the Birth of Nation,” Moffatt-Ladd House & Garden Museum, 2024, https://www.moffattladd.org/about-the-family. ↩︎

- [1] Sara J. Purcell, “Whipple, Prince (fl. 1776-1783), revolutionary war soldier,” American National Biography, (Feb, 2000), https://www.anb.org/search?q=prince+whipple&searchBtn=Search&isQuickSearch=true. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0200336; “Prince Whipple & Dinah Chase Whipple,” Moffat-Ladd House & Garden Museum, 2024, https://www.moffattladd.org/prince-whipple-and-dinah-chase. ↩︎

- “Prince Whipple & Dinah Chase Whipple.” ↩︎

- “5 Generations and the Birth of Nation;” “Prince Whipple & Dinah Chase Whipple.” ↩︎

- Larry A. Greene, “A History of Afro-Americans in New Jersey,” Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries 56, no. 1 (1994): 14, https://jrul.libraries.rutgers.edu/index.php/jrul/article/view/1731/3172. ↩︎

- Harry Schenawolf, “Washington’s Crossing and African American Prince Whipple: Fact and Fiction,” Revolutionary War Journal (Feb 21, 2023), https://revolutionarywarjournal.com/african-americans-in-the-american-revolution-prince-whipple-fact-and-fiction/; Timothy Messer-Kruse, “What Freedom Meant to Prince Whipple, the Black Revolutionary War Soldier Famous for Rowing Across the Delaware,” Commonplace: The Journal of Early American Life, https://commonplace.online/article/what-freedom-meant-to-prince-whipple/. ↩︎

- “5 Generations and the Birth of Nation;” “Prince Whipple & Dinah Chase Whipple;” ↩︎

- “5 Generations and the Birth of Nation;” “Prince Whipple & Dinah Chase Whipple;” Schenawolf. ↩︎

- Candace Katungi, “’Following the Internal Whisper’: Race, Gender and the Freedom-Centered Trinity of Black Women’s Activism (1735-1850),” Dissertation, Cornell University (2019), 37, https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/1813/70077/1/Katungi_cornellgrad_0058F_11813.pdf. ↩︎

- “Prince Whipple & Dinah Chase Whipple;” Messer-Kruse. ↩︎

- “1779 Petition to the New Hampshire Government,” Independence National Historical Park, National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/inde-1779-petition-new-hampshire-prince-whipple.htm. ↩︎

- Jessica D. Marcoux, “Specialized Walking Tour on Slavery in Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Presenting Untold Stories at the Warner House,” Master’s Capstone, Southern New Hampshire University, 2024, 60. ↩︎

- “1779 Petition to the New Hampshire Government.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Arnie Alpert, “1779 Petition for Liberation from Slavery,” New Hampshire Radical History, April 28, 2021, https://www.nhradicalhistory.org/story/1779-petition-for-liberation-from-slavery/. ↩︎

- Roger Wood, “234 Years Later, 20 Enslaved Revolutionary War Veterans are Granted Freedom,” New Hampshire Public Radio (7 June 2013), https://www.nhpr.org/nh-news/2013-06-07/234-years-later-20-enslaved-revolutionary-war-veterans-are-granted-freedom; “Portsmouth Slaves Emancipated after 234 Years,” The History Blog (8 Jun 2013), https://www.thehistoryblog.com/archives/25572 ↩︎

- Heather Cox Richardson, “October 17, 2025 (Friday),” Letters from an American, Substack, https://heathercoxrichardson.substack.com/p/october-17-2025-friday; Donald A. Yerxa, “The Burning of Falmouth, 1775: A Case Study in British Imperial Pacification,” Maine History 14, 3 (1975): 149, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1758&context=mainehistoryjournal. ↩︎

- “Declaration of Independence: A Transcription,” July 4, 1776, America’s Founding Documents, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript. ↩︎

Bio:

Dr. Lawrence Howard is an independent scholar living and working in Northern Virginia. His research focuses on the Founding Era at the intersection of history, political philosophy, and rhetoric. The root of his research is examining the foundations of and the differing perspectives on key political concepts such as freedom, liberty, slavery, and tyranny.Larry has a multi-disciplinary academic background, having earned a doctorate in liberal studies from Georgetown University, an MS in Government Information Leadership from the National Defense University, an MSS in Strategic Studies from the U.S. Army War College, an MBA in Management from Frostburg State University, and a BA in Criminology from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He retired from the Army following a 33-year career as an infantry and civil affairs officer and is currently a federal employee working for the Army. When not working or hanging out in research libraries and archives, he enjoys hiking and traveling.