Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian and reviewer Al Dickenson

No president has an easy job. But imagine holding the position of president immediately after undoubtedly the best president the United States has ever had.

That was John Adams’ conundrum. Additionally, it is the subject of renowned historian Lindsey Chervinsky’s new book, Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents That Forged the Republic. Initially released last year, in the midst of a politically fraught election season, Chervinsky places the modern world into a context we should all understand better: the history of the 1790s.

After a brief introduction regarding the Revolutionary War, the early republic, and George Washington’s presidency, readers are thrown into John Adams’ presidency. Federalists opposing Democratic-Republicans (commonly referred to as simply “Republicans” in Chervinsky’s text, as they referred to themselves), the Americans opposing the French, the North opposing the South, Federalists opposing Federalists: it seemed there could be no peace in the nation so split apart. Yet the nation stood for another 220 years. Why is that?

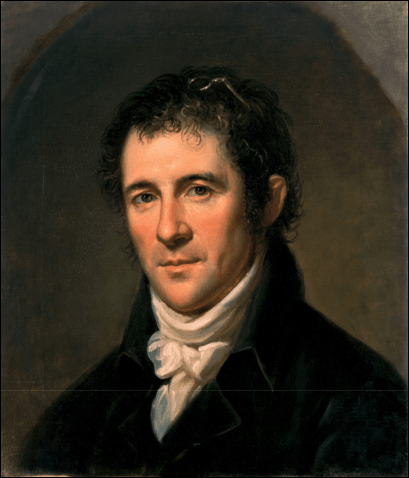

Chervinsky argues that the reason we are a nation today relies on how John Adams served his presidency, specifically the power sharing he enacted in his cabinet amongst Republicans (like Vice President Thomas Jefferson), Federalists (like Secretary of State Timothy Pickering), and Archfederalists (like Secretary of War James McHenry), the successful navigation of foreign affairs (see the ongoing French Revolution, specifically the XYZ Affair), and the peaceful transfer of power.

The final focus of Chervinsky’s book, Adams’ loss in the 1800 election, perhaps offers the most original outlook on Adams’ presidency. Being the loser of the election, and being the first incumbent president to lose an election, historians have often treated Jefferson a little kindlier than Adams. Where Chervinsky’s work shines, however, is in showing how these great, powerful men, the leaders of their respective parties, differed in how they saw power, and in how they wielded it.

Little scholarship focuses on Jefferson’s machinations to gain the presidency. Rarely researched are his Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, which called for nullifying federal law, even though these ideas were eventually adapted into various Confederate causes and mentalities in the following decades. Nor are the essentially political and emotional blackmail Jefferson laid on Federalist members of Congress who refused to vote for him over Aaron Burr. Jefferson threatened the members of Congress with, in essence, secession of Republican states if they did not pick a president soon, given that this was the only election in American history where the House of Representatives made the presidential selection. The dirty tricks of politics manifested themselves in this election, including smear campaigns against Adams and unfounded warnings that the Federalist Party would forego the will of the people and simply appoint a new, Federalist president.

Compare this to John Adams, who, while certainly desirous of a second term, largely laid low during the turmoil occurring on the other side of the Capitol. When presented with suggestions to keep himself as president, he refused. When asked to annul the election, Adams refused. When asked to stand for himself and campaign in the final months of the election season, and during the contingent election in the House between Jefferson and Burr, Adams refused and stayed silent. He did not cling to power, nor did he view his opinion better than that of the American people who voted for a Republican and the House members who would choose the next presidency. Though he was a lame duck president in every sense of the word, he held true to his convictions of propriety in politics, though privately he fumed.

In this way, though history often sheds more light on the winner, makes historians wonder what other ways “losers” of an election may have impacted our politics and history. An interesting study question for any intrigued historian, but one that Chervinsky shows is vital to understanding American history and modern politics alike.