Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian Ben Powers

Introduction

Nathaniel Greene is renowned for leading the Southern Department during the American Revolution, achieving significant strategic results against Lords Cornwallis and Rawdon, even though he lost several battles. Historian Theodore Thayer called him “the strategist of the American Revolution.”[1] Greene carefully planned his army’s movements to maximize maneuverability, chose to fight in situations with roughly equal numbers, strengthened support from auxiliary and irregular forces, and put the British in increasingly worse positions. His main goal was to keep his army active—success meant staying in the field and avoiding severe losses. This led Cornwallis to make decisions that resulted in his defeat at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781. Greene’s careful coordination of military actions to achieve strategic results hinted at what would later be called “operational art,” a concept later connected to leaders like Napoleon Bonaparte and Soviet theorists.[2] Greene’s skills showed the main elements of operational art, making him more than a strategist—he was an early example of an operational artist.

Some Definitions

The “operational level of war” is a twentieth-century concept describing military activities between the tactical level (winning battles) and the strategic level (achieving national aims through armed force and other instruments of power). In current doctrine, tactics involve sequencing forces in time and space to accomplish missions like seizing terrain. Strategy is how national leaders and senior commanders use available means to achieve defined ends. The operational level connects these two, as theater commanders sequence campaigns to achieve strategic objectives, a concept relevant for analyzing Greene’s approach.

Comparing Greene’s actions to a modern theoretical construct may seem anachronistic. However, it serves two purposes: First, it explains how a general who never won a tactical engagement still achieved campaign success. Second, it helps clarify the dynamic between strategy and operational art in Greene’s generalship. Labeling Greene’s efforts as “strategy” alone oversimplifies his achievements. While calling him a good strategist is accurate—he drove Cornwallis from the Carolinas—understanding Greene as an “operational artist” invites deeper inquiry into how he sequenced actions to achieve campaign effects.

The operational level of war requires a commander to achieve synergy among diverse forces in a broad theater. This synergy is created through operational art—a process evident in Greene’s Southern Campaign.

Superior technology, such as railroads in the Civil War or wireless radios in WWII, can help coordinate military actions. Greene did not have these advances. He worked with basic weapons like flintlock guns and muzzle-loaded cannons. Without new ways to move or communicate, he relied on creative leadership to make sure his forces worked as one.

Greene’s command philosophy granted subordinates wide latitude within his intent. He complemented this with a firm grasp of geography and maintained open communication with partisan leaders and civilian administrators, securing information and logistical support vital to his campaign strategy. This combination of decentralized execution, situational awareness, and collaborative communication provided Greene with a robust foundation for operational art, enabling his Southern Campaign success.

Greene’s Development in the Early Stages of the War for Independence

Greene went to war as a novice in 1775, rising from private in Rhode Island’s Kentish Guard to commanding the Army of Observation that the Rhode Island legislature authorized to join the ranks of the New England militia units surrounding Boston, Massachusetts, in the wake of the “shot heard ‘round the world”. After June 1775, when these units were amalgamated into the new Continental Army and George Washington subsequently assumed command, Greene found himself in positions of greater responsibility.

Greene gained valuable experience with Washington’s main army in the early northern campaigns. He fought around New York City in the fall of 1776, then led troops in the retreat through New Jersey and fought at Trenton and Princeton. During the 1777 campaign, he led a division against William Howe’s British troops at Brandywine Creek and Germantown, Pennsylvania. At this time, Greene focused just on the tactical side of war—winning battles to support Washington’s goals and plans.[3]

Howe eventually took Philadelphia. Washington’s army escaped to Valley Forge to regroup. During the winter before the 1778 campaign, Washington made Greene Quartermaster General, in charge of getting supplies for the troops. Greene kept his rank as a combat officer and led troops at Monmouth, New Jersey, and in Rhode Island. During this period, he learned valuable skills in coordinating supplies and collaborating with civilian leaders, which would aid him in his later command.

Performance in the Southern Campaign

Britain reached its high point in the South in the summer of 1780. Clinton captured Charleston in May and seized inland outposts before returning north, leaving Cornwallis in charge. Gates led Continental forces south, only to suffer a significant defeat in August. Soon, only partisans like Francis Marion and Andrew Pickens opposed the British. Greene briefly found himself in command of the Hudson River post at West Point after the defection of Benedict Arnold to the British in late 1780. However, in October, Washington placed him in command of the southern army in the wake of Gates’ defeat.

When Greene took command, he applied northern lessons in new ways. He sent officers to scout terrain, especially river crossings. Greene coordinated with partisan forces under Francis Marion to harass British outposts, distract commanders, and gather intelligence. He also corresponded with civilian authorities to request supplies.[4] Greene moved to give the British a bloody nose by dividing his forces into a “flying camp” under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, while retaining command of the main body of American troops. Morgan won a decisive victory against Banastre Tarleton at Cowpens in January 1781 and then moved to reunite with Greene.

After Cowpens, Cornwallis’s 2,500–3,000 troops chased Greene’s 2,000 across North Carolina. Greene fled north of the Dan River in Virginia to protect his army. This gave him safety—the river blocked Cornwallis, while the Virginia militia and supplies allowed Greene to regroup. Cornwallis failed to force a battle and lost momentum.[5]

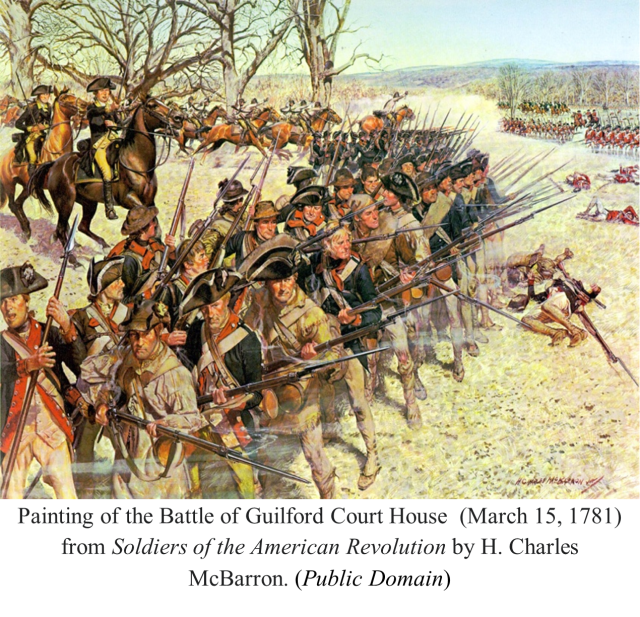

Greene kept his army together, setting the stage for the Battle of Guilford Court House in North Carolina in March 1781. This was a costly win for Cornwallis—his success on the battlefield led to heavy losses. The British could not easily replace lost troops and had to withdraw toward the coast. The Americans could rebuild their army and keep up operations. Cornwallis’s weakened position led him to move to Virginia, where his campaign ended at the Battle of Yorktown.[6]

Before Greene took command, Cornwallis had stopped open resistance in South Carolina. Greene used creative maneuvers and careful planning to block Cornwallis’ progress, hurt his forces at Guilford Courthouse—a battle the British won but at significant cost—and forced Cornwallis to focus on Virginia. Greene’s actions, though not resulting in clear victories, kept pressure on British outposts in South Carolina. This caused the new British commander to withdraw from the interior until, by the end of 1781, the British were confined to Charleston.

What did Greene accomplish?

For Greene, interrupting the British occupation and making it too costly for Cornwallis to continue was more important than winning individual battles. His goal was to disrupt British efforts and drain their manpower in South Carolina. He additionally tied partisan activities to his larger operational plans. In doing so, Greene acted as a prototype operational artist due to his ability to sequence military engagements to achieve desired strategic outcomes.

[1]Thayer, Theodore. Nathaniel Greene Strategist of the American Revolution. Twayne Publishers, 1960.

[2] Krause, Michael D., and R. Cody Phillips. Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art. Center of Military History, United States Army, 2005. https://history.army.mil/portals/143/Images/Publications/catalog/70-89-1.pdf.

[3] Gerald M. Carbone, Nathanael Greene a Biography of the American Revolution (S.l.: St. Martin’s Press, 2024).

[4] Ibid

[5] Waters, Andrew. 2020a. To the End of the World: Nathanael Greene, Charles Cornwallis, and the Race to the Dan.

[6] Babits, Lawrence Edward, and Joshua B. Howard. 2009. Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Univ of North Carolina Press.

Bio:

Ben Powers resides in Texas with his wife, K.C., and four children, Arthur, Michaela, Emma, and Jordan. He holds a master’s degree in strategic leadership from American Military University and served 24 years in the United States Army, retiring as a lieutenant colonel. Ben is an author, YouTuber, and President of the Board of Directors of the American Veterans Archaeological Recovery Project (AVAR). He participated in fieldwork in Barber’s Wheatfield on the Saratoga Battlefield in the fall of 2021.