Virginian Landon Carter was vocal about the latest pamphlet sweeping through the American colonies in 1776. In several diary entries from the first four months of that momentous year, he commented on Common Sense, written anonymously “by an Englishman.” Carter described its contents in February as “rascally and nonsensical as possible, for it was only a sophisticated attempt to throw all men out of principles.” By April, as he continued to criticize the work, he reached a conclusion about its author: “I begin now more and more to see that the pamphlet called Common Sense, supporting independency, is written by a member of the Congress …” Carter could not have been further from the truth.

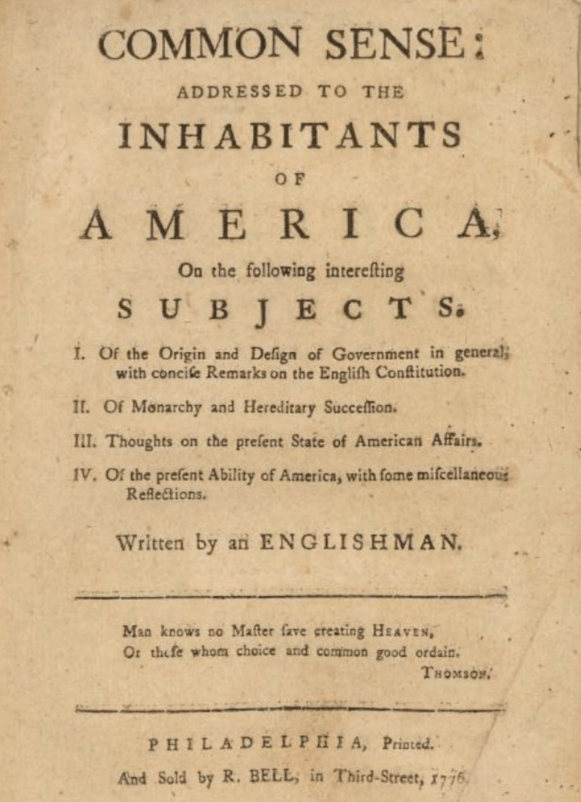

“An Englishman” was, in fact, an apt description for the author of Common Sense, first advertised to the American public on January 9, 1776, and first released on January 10. Thomas Paine was an Englishman—born there and, by most measures, matured there as a failure. He failed at his corset-making business. Teaching, collecting taxes, privateering, and working as a grocer—none of these occupations suited him either. He married twice (his first wife died in childbirth), and his second marriage collapsed. Amid this string of failures, Paine found success with the written word, which caught Benjamin Franklin’s attention in England in 1774. With little left for him in England, Paine embarked for America, arriving later that year. There, he scraped by as a writer, publishing essays in Philadelphia newspapers.

Continue reading “250th Anniversary of the Release of Common Sense”