Everyone has heard of the “shot heard round the world” at the North Bridge, or the first shots of the war on the early morning of April 19, 1775 at the Lexington Green. But few people know about events that transpired in New Hampshire four months before Lexington and Concord. The events at Fort William and Mary on December 13 and 14 1774 were just as critical to the step toward war as the September Powder Alarm or the later Salem Alarm in February 1775.

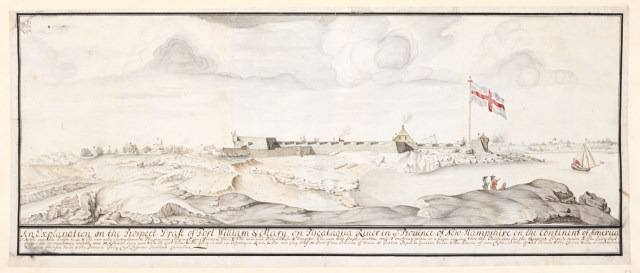

In response to the Massachusetts Powder Alarm in September 1774, colonial Whig leaders in nearby colonies began to make plans to “capture” local and colonial powder supplies. The crux was the issue of who really owned the gunpowder. Whig leaders believe they owned the power, the colonial militias. Royal leaders, Gen. Gage specifically, believe the powder was the “King’s Powder.” So any attempt to take the powder, was theft and treason. On December 3, 1774 the Rhode Island Assembly ordered the removal of cannons and powder from Fort George in Newport. On December 9, local militia carried out the order without any incident. Gage began to look at larger powder supplies that he believe were vulnerable. One large such supply was located at Fort William and Mary, located near Portsmouth, New Hampshire. This fort was isolated on the island of New Castle, at the mouth of the Piscataqua River. Located here was a small garrison of six men, guarding the fort and its supply of gunpowder.

Paul Revere and his other Patriot leaders in Boston became expert spies and soon received word that Gage was to send a contingent of British marines to Fort William and Mary. On December 13, Revere set out from Boston to Portsmouth to warn them of the coming expedition. Though the British navy was active in the area off of Portsmouth, Gage ironically made no plans to send an expedition to the fort. That would matter little in what happened next.

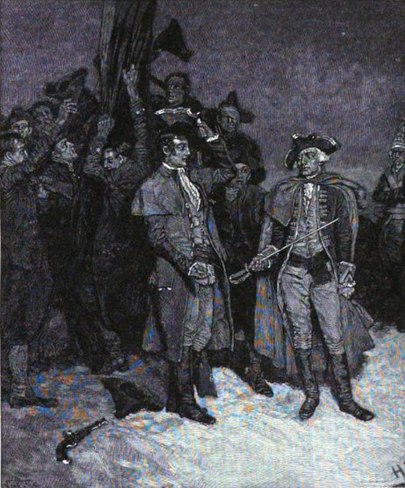

As Revere arrived in Portsmouth that afternoon, he gave the news of the supposed British expedition to the local Committee of Correspondence. Soon the local militia organized and, on the next day, nearly 400 militiamen assaulted the fort. The six-man British contingent inside the fort refused to surrender. They even fired three of their cannon at the attacking militiamen. For the first time, colonists were in open combat against British troops. The contingent eventually surrendered, having suffered a few injuries but no fatalities. That afternoon, the militia hauled away nearly 100 barrels of gunpowder. The next day nearly a thousand militiamen led by John Sullivan, arrived in Portsmouth due to the rider notification system. With no British to fight, these men assisted in going back to the fort to carry away muskets and cannon. Gage got word of Revere’s presence in Portsmouth and soon sent a small force from Boston to Portsmouth via the British navy. This force arrived the next week and at that point, there was nothing left of substance in Fort William and Mary.

The events at Portsmouth led Gage to be more aggressive in establishing a more coordinated spy network. As the new year began, Gage’s communications with England forced British officials to realize that this opposition was not like those in years past. The Patriots were arming themselves and establishing their own government in an affront to British authority. Former Prime Minister William Pitt, now sitting as a member of the House of Lords, knew the colonies well. He was well liked by the colonists, and he sought a compromise. He predicted the colonials would not back down and soon war would erupt between Great Britain and its colonies. Pitt proposed to remove British troops from Boston to lessen the tensions and to repeal the Coercive Acts. Both ideas were rejected overwhelmingly by Parliament.

In response to the news that the Continental Congress convened, Parliament on February 9, 1775, declared: “We find, that a part of your Majesty’s subjects in the province of the Massachusetts Bay have proceeded so far to resist the authority of the supreme legislature, that a rebellion at this time actually exists within the said province.” Now there was no doubt how the “Patriots” were viewed by Parliament and the King; they were rebels.

The events at Fort William and Mary were part of a succession of tense encounters between British authorities and local Whig leaders. Each one built on the tension from the previous. It is amazing that the “attack” by the New Hampshire militia on the fort, attacking the King’s troops, did not lead directly to war then. It would take four more months before another armed conflict sparked a revolutionary war.

To learn more about the Fort William and Mary 250th, visit: https://fortwilliamandmary250.org/

To read more about the events leading up to Lexington and Concord, visit the Savas Beatie website to purchase “A Single Blow: The Battles of Lexington and Concord and the Beginning of the American Revolution” by Phillip S. Greenwalt and Rob Orrison