It is well known that the French ardently assisted the Americans during the Revolution, and we often remember names like Lafayette, Rochambeau, de Grasse, and others. It is not so well known how the Spanish aided the American cause, nor the dedication of one person in particular.

Continue reading “Spanish Diplomat Miralles at Morristown, NJ”Author: Bert Dunkerly

Engagement at Osborne’s Landing, VA

During the Revolutionary War, the individual states formed their own navies for local defense and military operations. These state navies existed simultaneously with the Continental Navy. Like many state navies, Virginia’s began when the war started and there was a need to defend the state’s coastline and waterways, just as troops were organized to defend its land. The Virginia State Navy patrolled the Chesapeake Bay, provided security on its rivers, and even went to Europe and the Caribbean to bring back supplies.

After several years of inactivity, by 1781 the war had returned to Virginia. British troops occupied Portsmouth and used it as a base for raids. Governor Thomas Jefferson scrambled to get the state’s defenses ready.

British forces under General Benedict Arnold capture the fledging capital of Richmond, where he dispersed local militia and destroyed supplies. Arnold withdrew to the British base at Portsmouth, but the redcoats would soon be back in the area.

Marching south with reinforcements from New Jersey was General Lafayette. By late April he reached Hanover Court House, and continued on towards Richmond.

On April 8 General Phillips from Portsmouth up the James River to City Point. From there they moved on to Petersburg. The town was an important crossroads, port, and supply base for the Continental army. Generals Friedrich Von Steuben and Peter Muhlenberg had been gathering militia here, and they made a stand just south of the town on April 25. The British drove the defenders back, and the Americans retreated to Richmond. Phillips followed, intending to again capture the state capital.

As part of the British advance, General Arnold with the 76th, 80th, and some Jaegers (German riflemen) and Queen’s Rangers moved towards Osborn’s Landing on the James River. They arrived on April 27 and incredibly, won a naval battle without a navy!

Osborn’s Landing was a wharf about a dozen miles south of Richmond on the west bank of the James River. Assembled here were several merchant ships and the entire Virginia State Navy- nine warships with severely understrength crews. Across the river on the eastern bank were local militia from Henrico County.

Arnold sent a message to the American commander (whose identity is not recorded), “offering one half the contents of their cargoes in case they did not destroy any part.” The nameless American commander sent word, in answer, “We are determined and ready to defend our ships, and will sink them rather than surrender.” With that Arnold took them up on their offer.

The Queen’s Rangers and Hessian Jaegers charged down to the wharf, while the two British infantry regiments provided covering fire. Arnold also deployed two 3-pound and two 6-pound guns, which opened fire on the American ships “with great effect.” The Tempest became a primary target, and the Jaegers advanced, “by a route partly covered with ditches, within thirty yards of her stern.” The rifle fire prevented the crews from properly manning their guns on deck.

British artillery fire severed the rigging of the Tempest, and she began to drift, so the crew abandoned the ship. The other warships were also taking fire, and their crews abandoned them as well. Along with the Tempest, the other large warships lost were the Renown and the Jefferson.

The British destroyed the entire Virginia State Navy, and captured twelve private ships with 2,000 hogsheads of tobacco, flour, rope, and other supplies- all without a single ship of their own in the fight.

Phillips arrived at the town of Manchester, opposite Richmond, and Arnold’s forces joined them after moving up from Osborn’s. The British prepared to cross the shallow river and take the capital for the second time in three months. Yet the arrival of Lafayette on the high ground above the river convinced the British to turn back.

There are few reminders of the Revolution in the Richmond-Petersburg area. Today the site of Osborn’s Landing is inaccessible. Across the river, on the eastern shore, is a county boat landing and picnic area, with historic markers about the engagement. Ironically, Governor Thomas Jefferson’s grandfather, also named Thomas Jefferson, was born at Osborne’s Landing in 1677.

Preservation Victory at Short Hills Battlefield

Never heard of the battle of Short Hills, NJ? That’s’ not surprising, but its finally getting some recognition. It was the largest engagement since Princeton five months earlier, and was one of the first battles for the newly reorganized Continental Army.

In June, 1777 the main American force of about 8,000 was camped at Quibbletown in Middlesex County, not far from Perth Amboy and Staten Island, both occupied by the British.

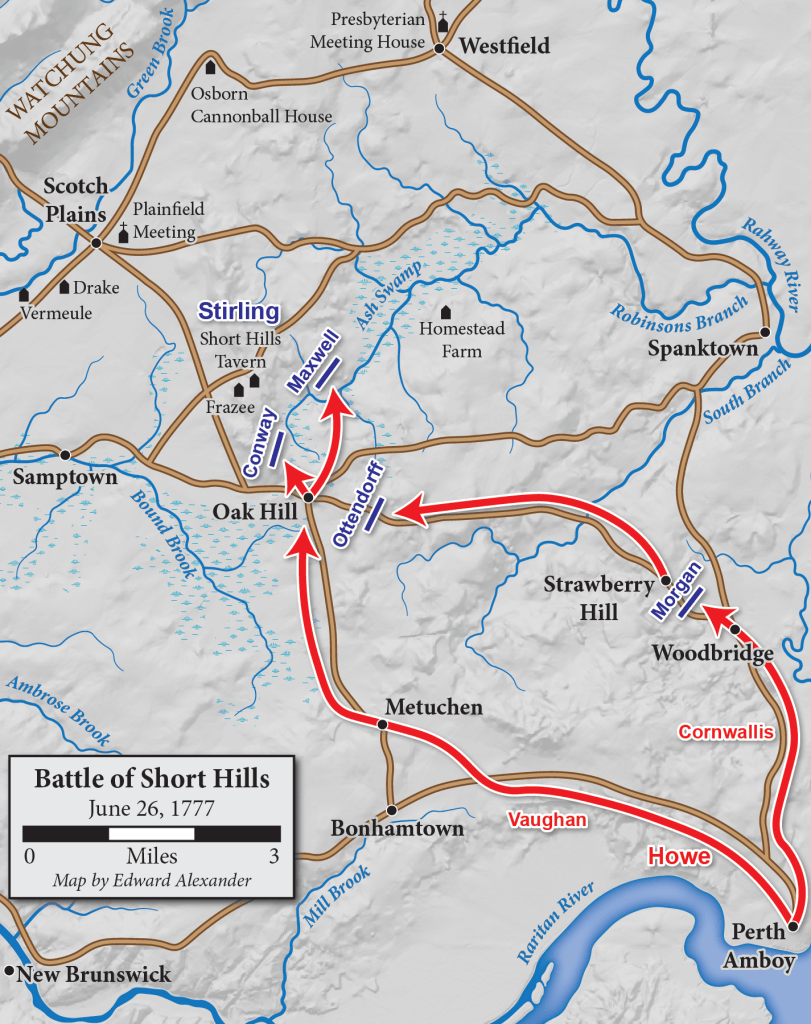

British forces under General Cornwallis left Perth Amboy at one o’clock in the morning on June 25, 1777. They engaged the Americans in the Battle of Short Hills, near the modern Union/Middlesex County Line. Another column, led by General John Vaughan, accompanied by General William Howe, moved toward New Brunswick then turned north toward Scotch Plains by a more southerly route. They planned to destroy Stirling’s isolated division between the two wings, and force Washington into an engagement. Stirling had two brigades, Brigadier General Thomas Conway’s Pennsylvanians and Brigadier General William Maxwell’s New Jersey troops. In all Stirling had about 1,798 men, more than 16,000 were bearing down on him.

(map by Edward Alexander)

Lafayette at Brandywine

Marquis de Lafayette was a French aristocrat serving in the French army, and recently married, when the Revolution broke out in America. He followed events with interst, and was motivated to come and fight with the Americans.

He arrived in March, 1777, nineteen years old and eager. He immediately formed a friendship with Washington, and was an aide on his staff. In the meantime British forces had invaded Pennsylvania, intent on capturing Philadelphia. Washington’s army took a position behind Brandywine Creek, and the British attacked on September 11, 1777. British troops had flanked the Americans, and reinforcements were rushed to the threatened sector, making a stand on Birmingham Hill.

Eager to get to the fighting, Lafayette and a group of French officers rode to the unfolding battle at Birmingham Hill, arriving as the action was at its hottest. Approaching from the south, they rode up the Birmingham Road, and turned to the left, coming in behind the brown-coated troops of General Thomas Conway’s Pennsylvania brigade.

Continue reading “Lafayette at Brandywine”The Revolution’s Impact on Pennsylvania’s Pacifist Communities: Part 2 of 2

Following the September, 1777 battle of Brandywine, wounded soldiers were dispersed across southeastern Pennsylvania for treatment, and some ended up at a hospital in the small Moravian town of Lititz, near Lancaster. The Moravians had many settlements in this part of the state. The Moravians, like the Quakers, were pacifists, and also assisted in humanitarian efforts like treating the wounded.

General Washington sent army surgeon Dr. Samuel Kennedy here to establish the facility. The army took over the Brother’s House, home to the community’s single men, who were forced to find shelter elsewhere. Moravians lived and worked in separate groups: single women, single men, married women, married, men, etc. Wounded from Brandywine arrived, and more arrived following the November battle of Germantown.

Continue reading “The Revolution’s Impact on Pennsylvania’s Pacifist Communities: Part 2 of 2”The Revolution’s Impact on Pennsylvania’s Pacifist Communities Part 1 of 2

Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn, was a Quaker, and insisted on morality and fairness for his government: fair treatment of Native Americans and religious freedom for all citizens.

By the time of the Revolution the colony was 90 years old and a variety of religious groups found safe haven in the colony, including Huguenots, German Pietists, Amish, Mennonite, Dutch Reformed, Lutherans, Quakers, Anglicans, Protestants, Dutch Mennonites, Jewish, and Baptists.

Quakers are perhaps the best known religious group that thrived in Pennsylvania. The Society of Friends emerged in England in the mid-1600s, and were persecuted for their beliefs. William Penn, an aristocratic Quaker convert, received a land grant as payment for a debt from the crown, and made religious toleration a cornerstone of the colony. When armies invaded Pennsylvania in 1777, the state’s Quakers were impacted. Refusing to be active participants, they did offer humanitarian aid to both sides.

Continue reading “The Revolution’s Impact on Pennsylvania’s Pacifist Communities Part 1 of 2”The Revolution in Richmond: Part 3 of 3

When Benedict Arnold’s troops departed in January, 1781, Richmond had not seen the last of redcoats. That spring British troops returned to the area, occupying Petersburg. Then Lord Charles Cornwallis arrived in the state with a larger British force, having marched north from Wilmington, NC.

Cornwallis’s army marched far and wide across the Commonwealth that summer, reaching Ox Ford on the North Anna (scene of a Civil War battle in 1864), and west towards Charlottesville. Returning to the east, Cornwallis’s forces marched into Richmond in June on the Three Chopt Road, now a major US Highway. That summer General Lafayette led American troops in Virginia, but his force was too small to directly challenge the British, and he stayed out of striking distance.

Over 5,000 Redcoats, Germans, and Loyalists marched down Main Street, all of the troops who eventually ended up at Yorktown. From June 17-20, redcoats again patrolled the dusty streets of the state capital. During those four days they destroyed some homes (under what circumstances it is not clear), piled up tobacco in the streets and set fire to it, and destroyed valuable supplies like salt, harnesses, muskets, and flour. The streets that were once the scene of illuminations to celebrate the Declaration of Independence were now lit by the fires of destruction.

Various accounts noted the poor condition of troops: uniforms being tattered and many lacking good shoes. The weeks of hard marching were taking their toll. British officer John G. Simcoe wrote, “the army was in the greatest need of shoes and clothing due to the constant marching.”

Civilians peering out their windows would have seen a variety of troops: Scottish Highlanders, English Regulars from England and Ireland, Carolina Loyalists, Hessians, and runaway slaves who had joined them.

Cornwallis’s forces began their march early on June 20, moving down Main Street to the Williamsburg Road, heading east towards Bottoms Bridge. In so doing, they passed by the future site of the Civil War battle of Seven Pines, and the Richmond Airport. Traces of the old Williamsburg Road run parallel to Route 60 from Sandston to Bottom’s Bridge.

Lafayette’s pursing troops entered the town from the west on June 22nd, continuing on towards Bottoms’ Bridge the next day. We have only three brief descriptions of the American army’s pursuit through Richmond. They are all tantalizing, leaving us wishing for more details.

Lieutenant John Bell Tilden of the 2nd Pennsylvania Battalion described the unfinished canal and ruins of the Westham Foundry: “This day I went to see the curious work of Mr. Ballertine- he had made a canal one mile in length, and about twenty feet wide, alongside of James River, in the centre of which he had built a curious fish basket, and at the end of the canal was a grist mill, with four pair of stones. Bordering on which was a Bloomery, Boring mill and elegant manor house, which was destroyed by that devlish rascal Arnold.”

Virginia militia Colonel Daniel Trabue wrote, “Our militia was called for, and all other counties, also, and we all joined Gen. Lafayette. As he neared Richmond, Lord Cornwallis left the city in the evening. The next morning a little after sunrise. General Lafayette marched through the town with his army, each man’s hat contained a green bush. I thought it was the prettiest sight I had ever seen. Lord Cornwallis had retreated, and our army advanced after them, passing through the city some 3 or 4 miles and then halted on the river road.”

Captain John Davis of the 3rd Pennsylvania Battalion wrote, “This day passed through Richmond in 24 hours after the enemy evacuated it- it appears a place of much distress.”

Another Pennsylvanian, Lieutenant William Feltman of the 1st Battalion, noted that the British had “destroyed a great quantity of tobacco, which they threw into the streets and set fire to it.” Feltman had the opportunity to break away from the camp and enjoy some leisure in the town, writing, ‘spent the afternoon playing billiards and drinking wine.” The Continental troops camped that night at Gillies Creek, just east of the city, where the battle in January had begun. They rose at 2 o’clock in the morning to resume their pursuit.

The troops moved on to Williamsburg and Yorktown, where a two-week siege in October resulted in the British surrender. The Yorktown campaign was the culmination of the Revolutionary War.

Richmond recovered and grew quickly after the war. Today there are few reminders of the Revolution in Richmond. A few tangible places to visit include Wilton Plantation, the First Freedom Center, St. John’s Church, the Washington Monument on Capitol Square, and the site of the skirmish on Chimborazo Hill.

The Revolution in Richmond: Part 2 of 3

In Part I we learned how the British under General Arnold captured Richmond. In the meantime Governor Thomas Jefferson had fled, along with members of the legislature. The British occupied the town for 24 hours, destroying supplies and wrecking the Westham iron foundry, west of the village.

Continue reading “The Revolution in Richmond: Part 2 of 3”

The Revolution in Richmond: Part 1 of 3

Richmond, Virginia was a village of 300 homes during the Revolution. Its residents were concentrated in the modern neighborhoods of Shockoe Bottom and Church Hill. Most of its few houses lined Main Street, with warehouses and workshops along the waterfront where the James River is very shallow. Williamsburg was still the capital when the war broke out.

Although best known for its Civil War history, Richmond has many important sites related to the Revolution that are overshadowed by that later conflict. Foremost among them is St. John’s Church, where Patrick Henry gave his “Liberty or Death” speech in 1775.

Continue reading “The Revolution in Richmond: Part 1 of 3”The War on the Pennsylvania Frontier: Part 5 of 5: The war between Virginia and Pennsylvania

Although both states were involved in the Revolutionary effort, Virginia and Pennsylvania were also at war with each other over land west of the Alleghenies. This territory had been claimed by both since the days of their early charters in the 1600s.

During the Revolution, the land claimed by both states had rival governments, courthouses and militias. Pennsylvania’s Hannas Town was the seat of its Westmoreland County, while Virginia’s West Augusta County was headquartered at Fort Pitt.

Throughout the 1770s, rival justices and other county officials were arrested and held in prison at either Hannas Town or Fort Pitt. Each claimed jurisdiction over the other, and saw the other as illegal.

At one point, Pennsylvania Governor John Penn wrote to Lord Dunmore of Virginia that he was “surprised” at Dunmore’s claim on the land, enclosing a map showing it firmly in Pennsylvania. Dunmore responded by denying the claim and explaining it was part of his colony. Penn then wrote that he “request your Lordship neither grant lands nor exercise the government of Virginia within these limits.”

Going in person to Fort Pitt, Dunmore issued a proclamation that, “whereas the Province of Pennsylvania has unduly laid claim to … His Majesty’s territory…. I do hereby in His Majesty’s name require & command all of His Majesty’s subjects West of Laurel Hill to pay a due respect to my Proclamation, strictly prohibiting the authority of Pennsylvania at their peril.”

Continue reading “The War on the Pennsylvania Frontier: Part 5 of 5: The war between Virginia and Pennsylvania”