Part Three

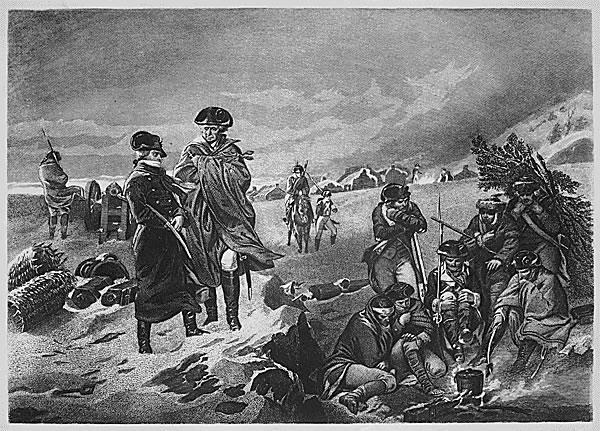

On February 23, 1778, Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben arrived at the Continental Army encampment at Valley Forge. He quickly ingratiated himself with George Washington and the commanding general’s cadre of staff officers. John Laurens would write a fortnight later;

“The Baron Steuben has had the fortune to please uncommonly….All the genl officers who have seen him, are prepossessed in his favor, and conceive highly of his abilities… The General [Washington] seems to have a very good opinion of him, and thinks he might be usefully employed in the office of inspector general…”

Steuben would assume the “acting” inspector general position three days after John Laurens penned the above letter, on March 12, 1778. Five days later, Steuben’s plan to train the Continental Army was approved by Washington. The transformation could begin.

Who was this “acting” soon-to-be permanent inspector general of the Continental Army? Steuben was born on September 17, 1730 in the Duchy of Magdeburg, in what is now eastern Germany. He journeyed with his father at age 14 on his first military campaign and joined the military at the young age of 17.

The last thirteen years before coming to America he had served in an administrative capacity for the Furst Josef Friedrich Wilhelm of Hohenzollern-Hechingen and was made a baron in 1771.

The baron arrived on American soil on December 1, 1777 and two months later arrived in York, Pennsylvania where he met with the Continental Congress on February 5, 1778. He found his way quickly to Washington’s encampment at Valley Forge.

On March 19, 1778, the first squad of men from the Continental Army undertook their first lesson with the baron. After learning the English words needed, von Steuben tasked each soldier of the 100 man squad to mirror him. The selected squad would follow the different maneuvers while listening to the baron “singing out the cadence.” While the squad went through their drills, another selected squad of onlookers studied the movements and then carried the drills to others.

The baron’s unique training regimens showed almost instant results, as von Steuben attested within a fortnight of the start of training. The soldiers “were perfect in their manual exercise; had acquired a military air; and knew how to march, to form column, to deploy, and to execute some little maneuvers with admirable precision.”

By the end of March, with Washington’s blessing, the entire army went under the drill regimen as instructed by von Steuben. The Prussian “acting” inspector general put his mark on all aspects of camp life as evidenced by the routine the soldiers adhered to while becoming acquainted with the manual of arms. “At nine a.m….new commands explained to each regiment at parade, then practice. By late afternoon, regiments were practicing by brigades.”

When a soldier fumbled a maneuver or the squad was not crisply moving through the drills, the baron’s temper would get the best of him and he would unleash a slew of epithets that was a unique blend of French and German with a few words of English sprinkled in for good measure.

The silver lining in these outbursts occurred when the baron would politely and calmy ask one of his assistant to translate into English the curse word of the moment. A light-hearted moment came when von Stueben asked his translator one time to, “come and swear for me in English, these fellows won’t do what I bid them.”

However, von Steuben won the trust of his trainees, as he instilled a sense of pride, of soldierly bearing, and when he did have his outbursts, those moments just underscored his similarities to the men he was training. As one biographer accurately summed up these occasions, the outbursts “humanized him” in the eyes of the rank-and-file.

There was one little secret that only the baron and his small staff were privy too; von Steuben was making up the drill and routine practices employed each day as he went along!

After the drilling of that day was completed and the baron snatched a quick bite to eat, von Steuben was off to his quarters where he scribbled out the lessons to be taught the following day.

Along with drill, camp life even improved, as von Steuben mandated changes that improved camp sanitation, which in turn, reduced sickness among the rank and file. By the end of the encampment, von Steuben controlled, according to historian Herman O. Benninghoff II, “the Valley Forge soldier’s introduction to command and control.”

On April 1, 1778, John Laurens wrote to his father and president of the Continental Congress, Henry Laurens about the major impact of von Steuben.

“Baron Steuben is making sensible progress with our soldiers. The officers seem to have a high opinion of him…It would enchant you to see the enlivened scene [of camp at Valley Forge]…If Mr. [Sir William] Howe opens the campaign with his usual deliberation, we shall be infinitely better prepared to meet him than we have ever.”

By May 1778 a Board of War member, a committee formed by the Continental Congress the previous year, wrote to a fellow board member the following lines, “America will be under lasting Obligations to the Baron Steuben as the Father of it. He is much respected by the Officers and beloved by the Soldiers themselves…I am astonished at the Progress he has made with the Troops.”

A fitting compliment came from the pen of George Washington who wrote to von Steuben near the end of the encampment at Valley Forge that “the army has derived every advantage from the institution under you, that could be expected in so short a time.”

Before von Steuben could finish the drilling of the soldiery that winter, the British stirred from their perch in Philadelphia and the lessons on the snowy plains of Valley Forge would be put to the test.