As we approach the 250th anniversary of Lexington and Concord, on April 14, 2025 another 250th anniversary is taking place but one that is much overlooked. When we think about the fight to end slavery in the United States, names like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and William Lloyd Garrison often come to mind. But America’s organized abolitionist movement actually began decades earlier—with a quiet but powerful group of reformers in Philadelphia.

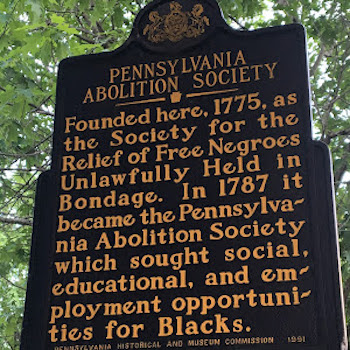

In 1775 the American colonies were on the verge of war with Great Britain, calling for freedom and independence. But even as they demanded liberty, many Americans—including some of the nation’s founders—continued to own slaves. Amid this contradiction, a small group of Philadelphia Quakers stepped up to challenge the injustice of slavery. On April 14, 1775 in Philadelphia, they formed what would become the first formal abolitionist organization in America, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.

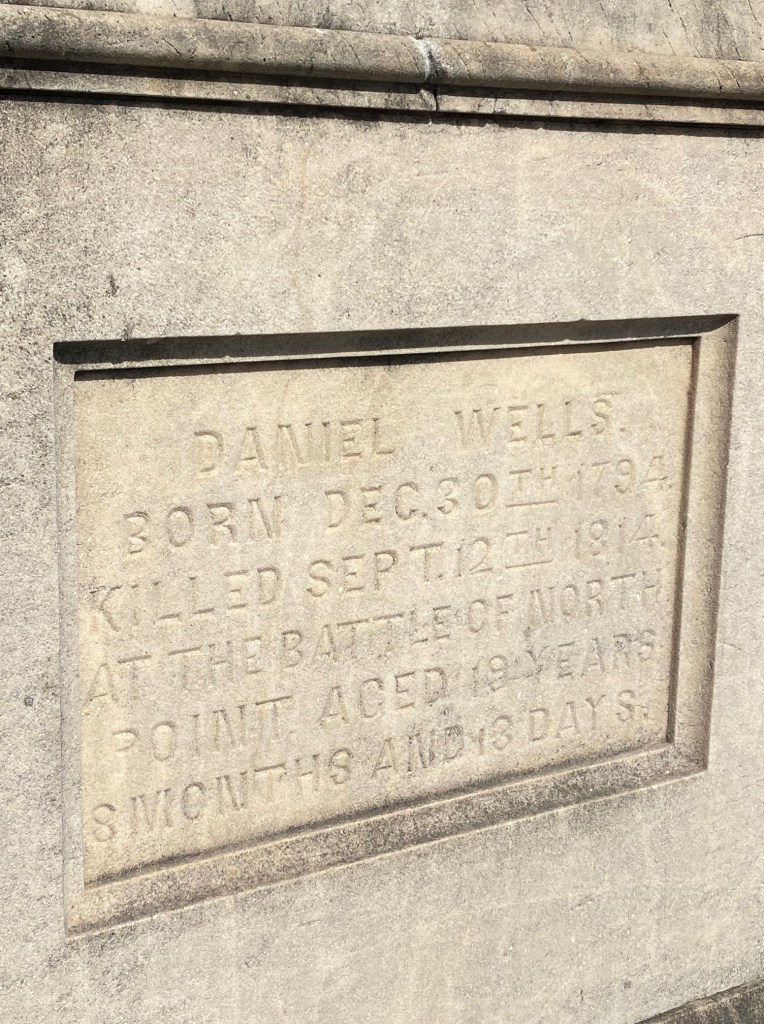

The name was long, but its mission was clear. This group was determined to help free Black people who were illegally enslaved or kidnapped into bondage. Their founding was quiet, overshadowed by the Revolutionary War, but it planted the seeds of a movement that would eventually reshape the nation.

At the heart of the Society were the Quakers (17 of the original 24 members were Quakers) formally known as the Religious Society of Friends. Quakers believed deeply in the equality of all people and had long spoken out against slavery. Many had already freed the people they once enslaved, and by the mid-1700s, anti-slavery had become central to their faith.

So in April 1775, a group of these Quakers, joined by a few like-minded allies, came together to create the Society. Their initial goal was modest but critical: to protect the rights of free Black people and prevent them from being illegally sold into slavery. This was not uncommon at the time, especially in cities like Philadelphia where Black communities—both free and slave—lived side by side. However, the outbreak of war later that year put much of the Society’s early work on hold. But their mission didn’t die.

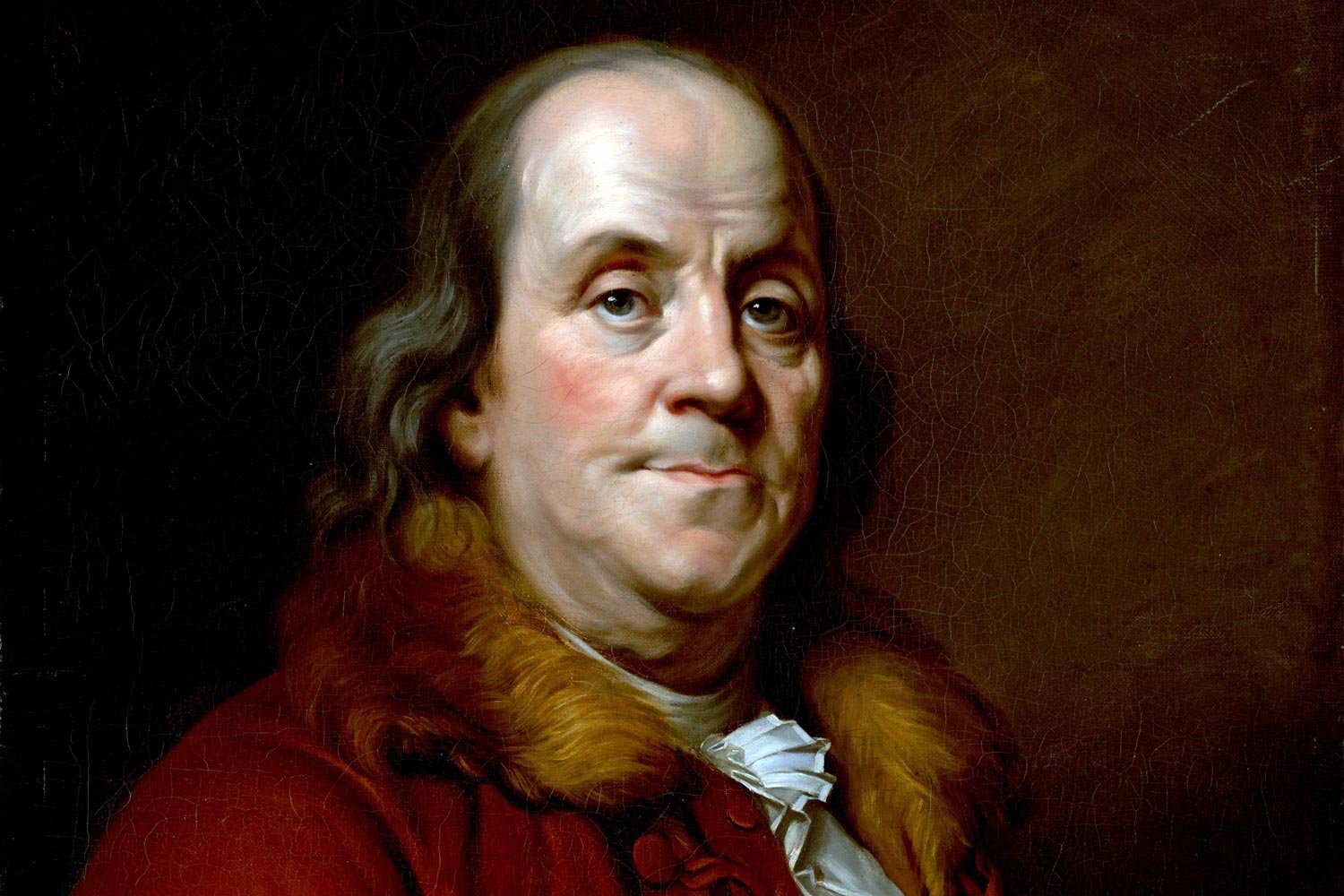

After the war, in 1784, the Society was revived with renewed energy and purpose. It was renamed the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage—still a mouthful, but a more expansive vision. Benjamin Franklin, one of America’s most celebrated founding fathers, became the Society’s president in 1787. Franklin had once owned slaves himself, but his views evolved over time. By the end of his life, he was a vocal critic of slavery and used his influence to support the Society’s goals.

This time, they weren’t just focused on defending free Black people—they were actively working to end slavery altogether. Their efforts were both legal and educational. The Society hired lawyers to defend kidnapped individuals, lobbied lawmakers, and even began promoting schools for Black children.

The Society’s work helped inspire real change. Pennsylvania became the first state to pass a gradual abolition law in 1780, a huge step forward. While the Society didn’t write the law, many of its members pushed hard for its passage and later worked to ensure it was enforced.

Still, the road was far from easy. The Society operated in a world where slavery was deeply entrenched—not just economically, but socially and politically. In the South, slavery was expanding. Even in the North, racism was widespread, and support for abolition was often lukewarm.

Despite these challenges, the Society’s model paved the way for the much larger abolitionist movements of the 19th century. It showed that legal advocacy, public education, and grassroots organizing could make a difference. It also helped define Philadelphia as a hub of anti-slavery activism that would later become home to figures like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth.