Emerging Revolutionary War is honored to welcome guest historian Daniel Welch to the blog. A brief biography of Mr. Welch is at the bottom of the post.

Several weeks ago I decided to take my usual weekend off of visiting American Civil War battlefields to take a moment to explore some American Revolutionary War historic sites just several hours down the road. Since it was a rather last minute decision, I was not completely prepared before visiting other than some basic historical context and a vague idea of operating hours and things to do while at these historic sites. So, if you want to follow the Continental Army during their experiences in the fall and winter of 1777-1778 read on to help plan a great weekend day trip.

Battle of Brandywine

If you want to follow these events as they happened, and in chronological order, began your day at the Brandywine Battlefield Park Associates site. Walking the site is free, but there is a charge if you want to go through the museum or on a tour of one of two historic homes on the property. Their hours are constantly changing so make sure you check their website. (click here), before you plan your visit. To go on a house tour, view the film, and go through the museum there is an $8.00 charge; the museum and film alone is $5.00. I would suggest, if you have the time, to take in the film and museum. The film lasts approximately twenty minutes while a thorough look of the museum could take one an additional forty minutes. Between the film and museum, a firm foundation to the events of September 11, 1777 will be in place before you head out to other locations associated with the battle. The house tour is a guided tour through Washington’s headquarters on the property and is conducted by a volunteer at the site. The tour took over an hour and a half, and considering that the home had burned to the ground nearly 100 years ago and has been rebuilt and filled with modern reproductions, your time would be better spent going to other sites associated with the battle.

Before leaving, make sure you pick up driving directions from the employees at the counter to get to Birmingham Friend’s Meeting House, and Sandy Hollow, the American’s second line of defense during the battle. Also, make sure to purchase the driving tour map of the battle of Brandywine. This map will take you to numerous other historic sites and homes within the Brandywine Valley that witnessed the events of that day. The cost is a mere $2.95. Plan an additional three to four hours to complete the driving tour.

Ultimately the battle proved to be an American defeat. Although he was defeated on the field, Washington and his generals were able to get large portions of the army to the rear through Polish General Pulaski’s assistance in covering the retreat. Despite the best maneuvers to save his army, Washington was unable to save Philadelphia and the city fell to the British just two weeks later on September 26, 1777. The British remained until June 1778.

Lunch

By now a late lunch would be in order. A great spot is the Black Powder Tavern. A tavern since 1746, it has a great Revolutionary War history, including a supposed visit by Washington himself. The restaurant’s name is related to a historical legend that none other than Von Steuben had ordered the tavern turned into a secret black powder magazine during the army’s pivotal winter at Valley Forge. The food here was great, as was the service and beer selection.

Valley Forge National Historical Park

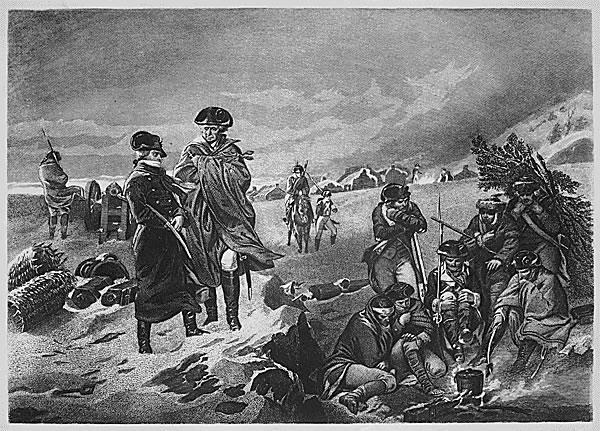

Following the defeat at Brandywine in September, and another engagement at White Marsh in early December, General Washington looked to put his army into a more secure camp for the coming winter. Active military campaigning for 1777 in Pennsylvania was over. Just twenty miles northwest of Philadelphia, the Continental Army faced numerous challenges here including a lack of food and shelter. Disease also spread during their time at Valley Forge. By February 1778, approximately 2,500 soldiers had perished.

To begin your visit here, start at the visitor center. The museum has its challenges. There is no discernible narrative to the exhibits; rather, numerous cases with laminated pieces of paper hanging on the side with corresponding images and item descriptions. Although there are some unique items on display, if it is busy you could wait at a particular case for the laminated cards to know what you are looking at. After a perusal of the museum, take in the free film. Although it is rather dated it provides a great overview of the winter encampment, its challenges, and outcomes. Between the film and museum, plan on spending an hour at the visitor center.

If you have additional time, take in the one and only National Park Service Ranger program offered. It is a rather short program, in length and walking distance, from the visitor center to the reconstructed Muhlenberg Hut sites. The program also echoes what is presented in the film. Before leaving the visitor center, I recommend getting the auto tour cd, as well as any updates on road closures. The park is currently under a significant amount of construction that has closed some roads and altered the driving tour route. The suggested driving tour cd is two hours in length. This would be a time allotment for those visitors who do not stop at each site, get out of the car, and explore all the stops along the route. You will want to get out and explore monuments such as those to the New Jersey troops, National Memorial Arch, von Steuben, and Patriots of African American Descent. You will also want to explore the several historic homes within the park that were used during the encampment, such as Varnum’s Quarters, Washington’s Headquarters, and the Memorial Chapel. My explorations, coupled with the driving tour cd, lasted nearly five hours.

Although it would be a long day, it can be done in one; however, if you wish to slow the pace of your visit, each site could be done on a separate day during your weekend. There is plenty of lodging in the area to accommodate this schedule. By visiting both of these historic areas and learning about the events of the fall through early spring 1777-1778, a greater picture can be viewed gleaned of military situation during the time period, as well as the tough composition of the Continental Army despite their defeats.

*Dan Welch currently serves as a primary and secondary educator with a public school district in northeast Ohio. Previously, Dan was the education programs coordinator for the Gettysburg Foundation, the non-profit partner of Gettysburg National Military Park, as well as a seasonal Park Ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park for six years. During that time, he led numerous programs on the campaign and battle for school groups, families, and visitors of all ages.

Welch received his BA in Instrumental Music Education from Youngstown State University where he studied under the famed French Hornist William Slocum, and is currently finishing his MA in Military History with a Civil War Era concentration at American Military University. Welch has also studied under the tutelage of Dr. Allen C. Guelzo as part of the Gettysburg Semester at Gettysburg College. He currently resides with his wife, Sarah, in Boardman, Ohio.