This article by ERW’s William Griffith first appeared on the American Battlefield Trust’s website on January 4, 2021. The original link can be found here.

The French and Indian War was in its fifth full year, and the tables had turned in Britain’s favor. As the larger conflict, the Seven Years’ War, raged throughout the globe, in North America, the British were one swift strike away from conquering the continent. The French in the Ohio River Valley, Great Lakes region, and Upstate New York had been thrown back on their heels and sent scurrying north into Canada leaving the road open for a British thrust against Montreal and Quebec. For the summer of 1759, the latter city, the capital of New France, would be placed in the crosshairs by an army commanded by Major General James Wolfe. If Quebec, situated along the most important water highway in Canada, the Saint Lawrence River, should fall, the French in North America would be squeezed into the region around Montreal. Pending any catastrophic failures by Britain’s army and navy and their allies elsewhere in the world, it would only be a matter of time than before New France was conquered.

James Wolfe and His Army

Thirty-two year old James Wolfe had served in the British Army for almost eighteen years when he was given command of the roughly 9,000-man force that was tasked with defeating the French in and around Quebec City in 1759. He was hard-nosed and did not always get along with his subordinate generals, Robert Monckton, George Townshend, and James Murray. The previous year he had been a brigadier general under Jeffry Amherst during the successful siege and capture of the fortress city of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia, and afterward led a campaign of destruction against the fishing villages of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. He then returned to England and secured a major generalship and command of the Quebec expedition. He arrived in Halifax in April 1759 and began training his force and preparing plans for his campaign.

Wolfe’s army was composed predominantly of professional British soldiers. Several hundred North American ranger units also complimented his force, which he described as, “… the worst soldiers in the universe.” He did not have much respect for colonial troops. On June 26, Wolfe’s men began landing at Ile d’Orleans in the middle of the Saint Lawrence River just to the east of Quebec City. Across the river, the French commander, the Marquis de Montcalm, prepared to oppose them.

The Marquis de Montcalm and Quebec’s Defenders

Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm, had been in command of France’s regular troops in North America since 1756. During that time he had put together an impressive string of victories at places like Fort Oswego, Fort William Henry, and Fort Carillon. As the attack on Quebec loomed, he was given command of all military forces on the continent, including the Canadian militia and marines. The previous harvest had not been good in Canada, and his army and the civilians in the city were on short rations, but relief came during the spring of 1759 when ships arrived carrying food and supplies. With this, Montcalm was determined to hold onto the city at all costs. He dug trenches outside the city and along the Saint Lawrence’s northern shoreline extending for nearly ten miles, welcoming a frontal assault from Wolfe. His army, consisting of over 3,500 French regular troops, included thousands more Native American allies and Canadian militiamen who were not accustomed to fighting in open fields against professional enemy soldiers. This important disadvantage would play a large part in Montcalm’s ultimate defeat.

The Campaign

When General Wolfe’s army began landing at Ile d’Orleans and subsequently Point Levis (directly across the river from the city) to the east of Quebec, he had initially hoped to force a landing on the northern shore just a few miles downstream at Beauport. However, he quickly discovered that Montcalm had heavily fortified the landing site, throwing a monkey wrench into his plans. This did not deter Wolfe, however, and by July 12, he had placed ten mortars and cannon at Point Levis and began bombarding the city itself. More guns were brought up and the bombardment continued for weeks in an effort to demoralize those within Quebec City.

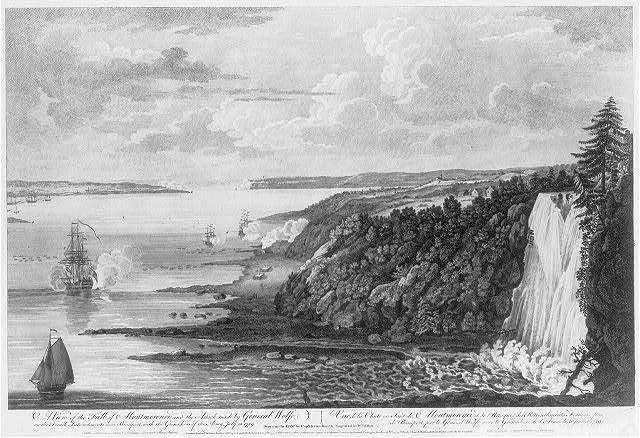

The best chance to defeat Montcalm was to force him out of his defenses and into an open field battle. Wolfe understood that his vigorously trained and superior disciplined regular troops would have the upper hand against lesser-numbered French regulars and their militia. His first attempt to accomplish this occurred on July 31, when he landed a force of grenadiers, light infantry, and rangers near Montmorency Falls further downstream from Beauport hoping to ford the Montmorency River and reach a position in the rear of the French lines. It failed miserably. Montcalm guessed correctly that an attack was coming from that direction and rushed men there to meet the enemy. The river’s tide prevented Wolfe from getting all of his troops in position on time and frontal assaults launched from the beach were beaten back with heavy losses. The British retreated, leaving behind 443 men killed and wounded. The first attempt to force a landing on the Quebec side of the river had failed, but it would not be the last. Wolfe turned his attention further upriver, where he hoped his prospects for victory would be more fruitful.

The Plains of Abraham

As the weeks passed following the debacle at Montmorency, the British probed the northern shore west of Quebec for a secure landing spot. During this time, Wolfe grew sick with a severe fever and kidney stones and believed his days were numbered. He recovered enough, however, to begin moving his army upriver about eight miles from the city not far across from Cap Rouge. It was decided that the landing would be made at Anse au Foulon, where a narrow gap and trail led to the top of the cliffs just two miles west of the city.

At four in the morning, September 13, Lieutenant Colonel William Howe (who would serve as the commander of the British Army in America during the Revolutionary War) came ashore with the light infantry and surprised and overwhelmed the enemy outpost above the landing site. The conditions for rowing the army into position that early morning had been perfect for Wolfe. Montcalm was caught off guard.

After securing the landing zone, Wolfe began moving his attack force of roughly 4,400 regulars onto the Plains of Abraham, an open field about a mile wide and a half a mile long in front of the city’s western defenses. Responding to the threat as quickly as could be done, Montcalm rushed some 1,900 French regulars and 1,500 militiamen and Native Americans to meet the British line. This was the open field fight that Wolfe had been yearning for ever since the campaign began.

As the French commander formed his men up in a line of battle, the British waited patiently across the field to receive their attack. Montcalm ordered his troops forward, and almost immediately his militiamen’s lack of experience and training in open combat became apparent as their formations wavered and some failed to advance close enough to the enemy line to fire effectively. One British participant described what happened next:

The French Line began … advancing briskly and for some little time in good order, [but] a part of their Line began to fire too soon, which immediately catched throughout the whole, then they began to waver but kept advancing with a scattering Fire.—When they had got within about a hundred yards of us our Line moved up regularly with a steady Fire, and when within twenty or thrity yards of closing gave a general [fire]; upon which a total [rout] of the Enemy immediately ensued.

The battle was over in just fifteen minutes as the British swept forward, claiming the field and capturing hundreds of prisoners. Both sides each lost over 600 men killed and wounded, including both respective commanders. Wolfe was mortally wounded and died a hero on the field. Montcalm, too, was hit by grapeshot in the abdomen and died the next morning. Five days later, Quebec surrendered. The French retreated further downstream to Montreal, attacked and failed to retake Quebec the next spring, and surrendered in whole on September 8, 1760, effectively ending all major military operations in North America during the French and Indian War. The battle for the continent between Britain and France was over.