First, thank you all for understanding with the technical difficulties of yesterday’s potential Facebook Live.

Over this past weekend, the 210th anniversary of the Battle of Bladensburg and the Burning of Washington by British troops took place. In a potential future tour, I was scouting out locations around our nation’s capital that are connected with the year 1814. Although some of the sites have been rebuilt, some of the history is preserved in museums, and one of the places is still occupied by the president of the United States, there is still a lot of history underfoot related to the War of 1812.

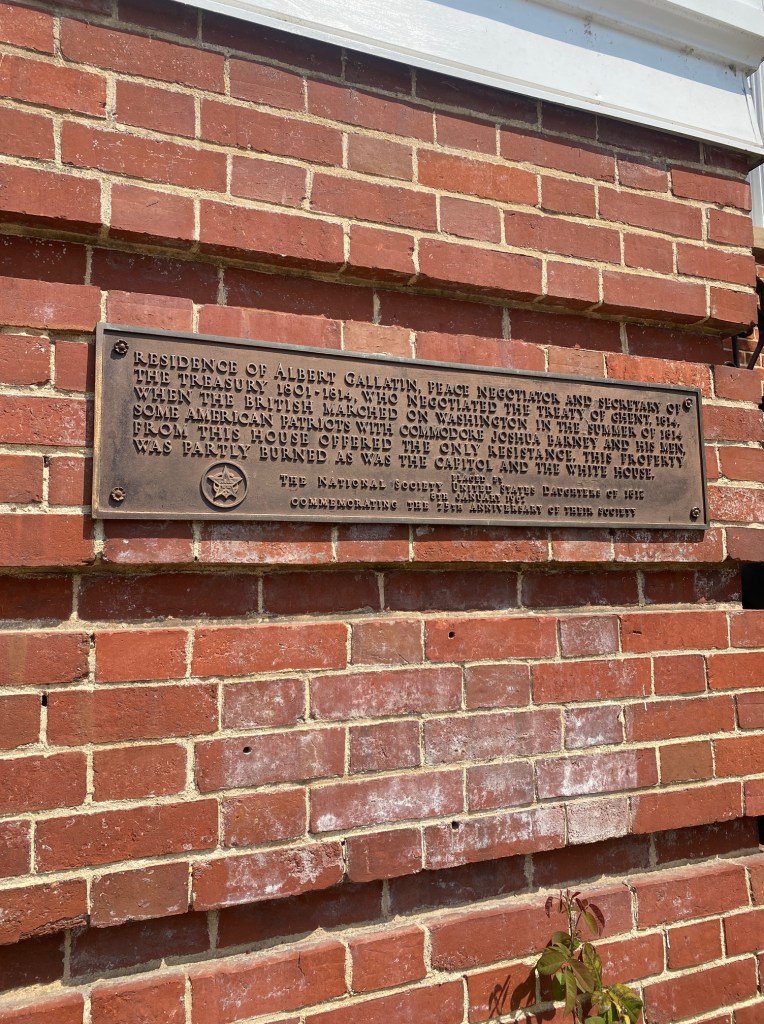

Some of that history is below. Robert Sewall built a house sometime between 1800 on 2nd and Maryland Avenue Northeast but with an inheritance from an uncle’s passing moved to southern Maryland. He rented the property to Albert Gallatin, who would serve as treasury secretary under both Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. In 1813, Gallatin left to become one of the United States peace commissioners in Ghent, Belgium charged with negotiating a treaty to end the War of 1812. William Sewall, Robert’s son, took responsibility for the house at that point. William served with Commodore Joshua Barney during the War of 1812 and records do not indicate he ever lived at the residence.

During the British march into the city, a group of Barney’s men took refuge in the residence and fired shots at the enemy column. Two British soldiers were killed and the horse of Major General Robert Ross was also struck. Ross ordered men into the structure to clear the snipers but not finding the culprits, the infantrymen burnt the property in retaliation. This would be the only private property burnt during the British incursion into Washington.

The property remained in the Sewall family, the house was rebuilt in 1820 and is now the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, a unit of the National Park Service.

After returning to Washington, the Madison’s took residence here, in the house of John Tayloe III. On September 8, 1814, the Madison family moved in and in an upstairs room, the president received the peace treaty negotiated in Ghent, Belgium. He ratified the treaty in the upstairs study on February 17, 1815. When the Madison family vacated the quarters, six months after moving in, Tayloe received $500 in rent from their stay.