It’s hard to overemphasize how important Common Sense was as a tool of persuasion.

Sure, we all know about it. “The idea that Common Sense played a pivotal role in moving the nascent revolutionary movement toward independence is universally acknowledged today,” says historian Jett B. Conner.[1]

Yet I’ve found that, beyond its generally accepted place in American history, most people don’t quite “get” Common Sense. Reading the document today—like anything written 250 years ago—poses a challenge for modern readers. The language doesn’t catch for us the way it did for readers of its time. We aren’t living in the same political context they were. We marinade in a much different, much more immersive media environment. These factors all remove us from the visceral impact Common Sense had.

In the early days of my teaching career, I taught public relations classes. I had been a PR professional prior to that, enticed to the academy, but I wanted my classes to be grounded in the professional standards established by the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA). They had criteria for academic programs that wanted PRSA certification. My university didn’t qualify because we didn’t have a specific major in PR at the time, but I nonetheless used their standards as the model for my classes. One of the standards at the time advocated teaching the history of PR.

Several PR milestones sprang from the political arena: Andrew Jackson’s first use of a press secretary in the White House; Teddy Roosevelt’s bully pulpit; the WWI-era Creel Commission; FDR’s fireside chats; the WWII-era Office of War Information, etc.

Common Sense made the list as the most significant piece of American writing to that point—a track specifically aimed at public persuasion. And boy, did it succeed! “Common Sense was the most radical and important pamphlet written in the American Revolution and one of the most brilliant ever written in the English language,” assesses historian Gordon Wood.[2]

Prior to Common Sense’s publication in January 1776, John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania in 1767–8 held the record as the most influential piece of public writing. Published in 19 of the 23 major newspapers in the colonies—as well as appearing in England and France—the letters opposed Parliament’s Townsend Acts, which imposed tariffs. Dickinson, a lawyer rather than a farmer, became one of the most famous men in America because of his twelve letters, which did much to unify the colonies in common cause against British taxation.

“Farmer’s Letters captured the spirit of the moment and Americans’ imaginations like nothing before,” says Dickinson biographer Jane E. Calvertt, “selling more copies than any other pamphlet to date. The response was immediate and resounding, going far beyond anything Dickinson could have anticipated.”[3]

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense eclipsed Dickinson exponentially—some 100 times larger, according to historian John Ferling.[4]

Timing helped. Bloodshed on Lexington Green, at the North Bridge in Concord, and all along the road back to Boston added urgency to public discussions. Closure of the port of Boston and the October firebombing of Falmouth, Maine—and the foreboding message it suggested to other colonies—heightened tensions even more. England was no longer some abstract entity across the ocean, but an intrusive force ready to impose its will through violence if necessary. “It was successful because it came precisely the time when people were ready for its message,” says historian Alfred F. Young.[5]

“The suppressed rage that animated Paine’s writing in Common Sense was another important factor in its success,” contends historian Scott Liell, who said “Paine felt, and made his readers feel, ‘wounds of deadly hate.’”[6]

Through 1775, the Continental Congress remained undecided on a course of action, with factions pushing for independence and others pushing for rapprochement. Therefore, news from Philadelphia did little to provide clear guidance for public sentiment.

“[T]he idea of independence was familiar, even among the common people,” John Adams later pointed out.[7] The idea just hadn’t yet crystallized.

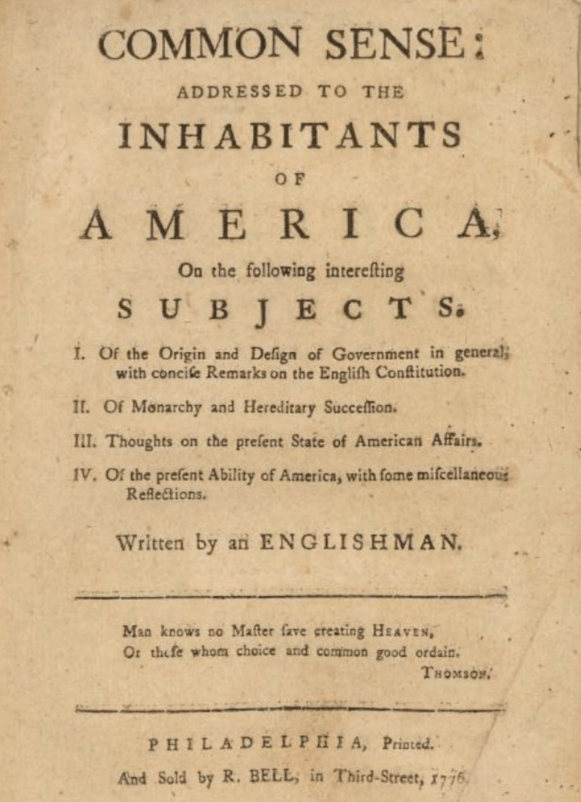

Common Sense—first published on January 10, 1776, as a 46-page pamphlet—became that crystal.

“[T]here is something absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island,” Paine wrote. Paine made such sentiments seem like statements of the obvious. Of course a continent shouldn’t be ruled by an island. Of course one honest man was worth more to society and in the sight of God than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived. Of course.

That was the genius of Paine’s writing.

To read it today, one wouldn’t appreciate how accessible it was to common folks or realize how often people read it aloud in taverns and inns so that even people who could not read could hear its ideas and engage in discussions. A reader today wouldn’t grasp just how hungry readers of 1776 were for Common Sense’s ideas.

“In weighing the influence of a tract, the active role of the reader is often underappreciated,” Young points out.

Reading is an act of volition. A person had to buy the pamphlet; one shilling was cheap as pamphlets went but costly to a common carpenter who might make three shillings a day or to a shoemaker had made even less and out of the question for a common laborer who earned one-eighth of a shilling a day. Or a person had to borrow the pamphlet, seeking out an owner, or respond to someone’s blandishments to read it. When it was read aloud, as it was in taverns and other public places, a person had to make a decision to come to listen or to stay and hear it out.[8]

In other words, readers had to actively want to read it—and they sometimes went to great lengths and expense to do so.

Common Sense sold somewhere around 125,000 copies within its first three months and, within its first six months, went through thirty-five printings—an astounding success considering the population of the American colonies totaled just under 3 million people.[9] A translation appeared for Pennsylvania’s German communities, and editions appeared in England and France.

Sales figures probably only scratch the surface of the pamphlet’s total circulation. “As its reputation and popularity spread,” says historian Scott Liell, “individual copies were read and re-read to countless assembled groups in public houses, churches, army camps, and private parlors throughout the colonies.”[10]

“Its effects were sudden and extensive upon the American mind,” pronounced Philadelphia physician Dr. Benjamin Rush, a friend of Paine’s who had suggested the title. Suddenly, the pearl-clutching in Congress became open, vigorous, public debate. (See Kevin Pawlak’s January 9, 2026 post for more info on the public reactions.) “The controversy about independent was carried into the news papers . . .” Rush recalled. “It was carried on at the same time in all the principal cities in our country.”[11] Indeed, in was in early February 1776 in a New York City bookshop—on his way from Boston to Philadelphia—that Adams first found Common Sense. (Adams would have his own complicated history with the pamphlet, which I’ll explore in a future blog post.)

To this day, Common Sense has never been out of print. It exists today as an icon, a relic, a foundational text we’ve all heard of. We accept its primacy as fact. But few people actually read it, and fewer successfully tune in to its urgency and immediacy. In commemoration of its 250th birthday, I invite you to take a closer look at a document you certainly know and think you know, and see what new sense you may be able to draw from it. (Read it here!)

[1] Jett B. Conner, John Adams vs. Thomas Paine: Rival Plans for the Early Republic (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2018).

[2] Gordon Wood, “Thomas Paine, America’s First Public Intellectual,” Revolutionary Characters (New York: Penguin, 2006), 209.

[3] Jane E. Calvert, Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson (London: Oxford University Press, 2024), 184.

[4] Ferling, 143.

[5] Aldred F. Young, “The Celebration and Damnation of Thomas Paine,” Liberty Tree: Ordinary People and the American Revolution (New York: New York University Press, 2003), 271.

[6] Scott Liell, 46 Pages: Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to Independence (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2003), 20.

[7] “From John Adams to Benjamin Rush, 21 May 1807,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5186.

[8] Young, 271.

[9] Young says, “Scholars have generally accepted a circulation of 100,000 to 150,000 copies (although none of them make clear how they reached their conclusions).” Liberty Tree, 270.

[10] Liell, 16.

[11] Benjamin Rush, The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush, George W. Corner, ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1948), 114, 115.