I want to take a moment to give a shout out to the Quincy Historical Society in Quincy, Massachusetts.

For my upcoming ERW Series book on John Adams in the Revolution, Atlas of Independence, I included an appendix that highlights a number of Adams-related sites in his hometown of Quincy: his birthplace; the home he first lived in with Abigail; his later-in-life home, Peacefield; the “Church of the Presidents,” which includes his crypt; and several other cool spots.

One of the places I direct people is to Merrymount Park, which features two monuments to Adams and members of his family. The newer of the two consists of a statue of John that stands across a small plaza from a dual statue of Abigail and a young John Quincy. The distance symbolizes the distance between John and his family for much of his public life.

Sculptor Lloyd Lillie created the Abigail and John Quincy statues first, in 1997. They stood together in downtown Quincy along Hancock Street. John was installed across from them in 2001, separated by traffic. When the city redesigned downtown and created the new Hancock-Adams Commons in 2022, the statues were relocated to Merrymount Park to join an older monument already standing there.

That older monument was a little harder to investigate.

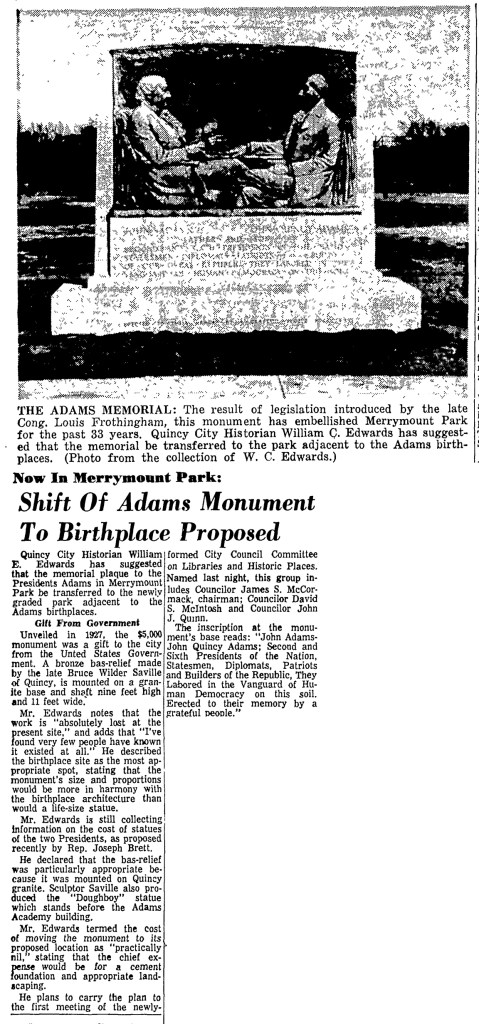

The monument itself is made from Quincy granite, a longtime staple of the local economy. A bas relief bronze tablet mounted on the granite shows John and an adult John Quincy—both as presidents—seated together for an imagined conversation with each other. An inscription reads: “Father and Son, Second and Sixth Presidents of the Nation, Statesmen, Diplomats, Patriots, and Builders of our great Republic, they labored in the vanguard of human democracy on this soil.”

Beyond that, I knew the memorial had once been moved to the site where the John and John Quincy birthplaces stand along Franklin Street, but I didn’t know when and I didn’t know when the monument came back to Merrymount. I couldn’t even find the year of the monument’s dedication or the name of the sculptor. The internet didn’t seem to know these things, and none of my reference materials referenced them.

And so it was that I reached out to the Quincy Historical Society to see if they might have anything in their archives that could help me out.

Archivist Mikayla Martin went above and beyond to assist, sending me a neat little bonanza of stuff! Since she sent me more material than I had room for in the book, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share my windfall here so that you, too, could benefit from the Quincy Historical Society’s kindness.

The memorial, as it turned out, was dedicated in 1927. The chief of staff of the United States Army at the time, Maj. Gen. Charles P. Summerall, served as master of ceremonies for the event, according to a clipping from the Patriot Ledger the historical society sent me:

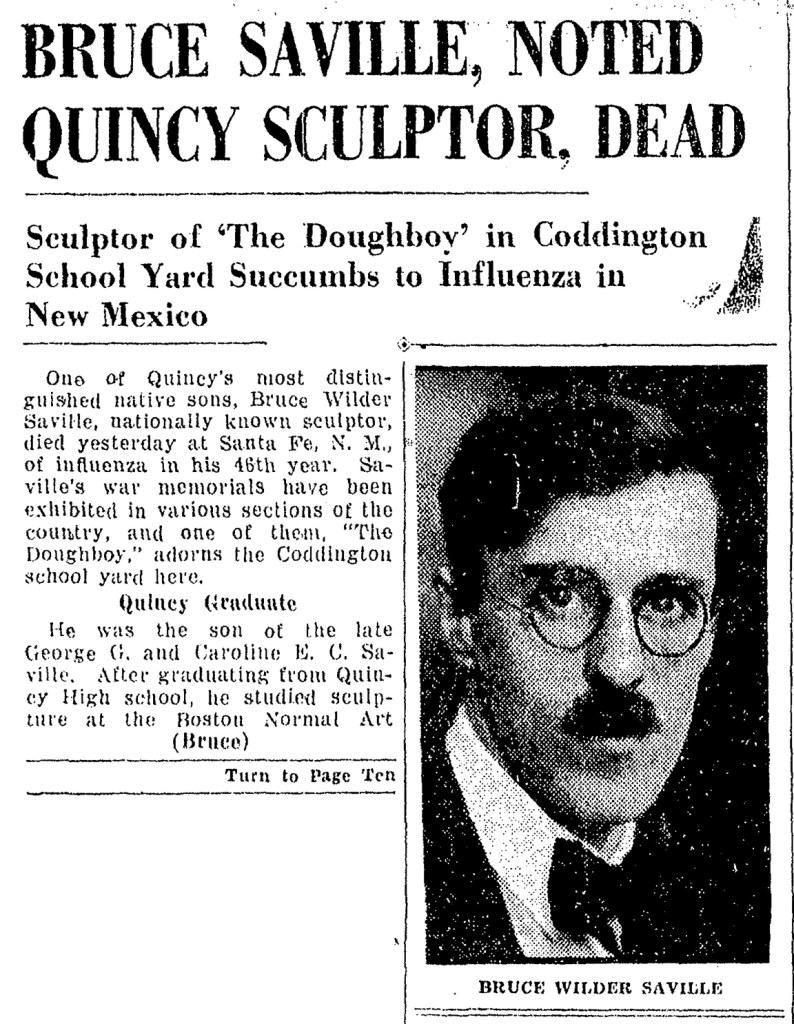

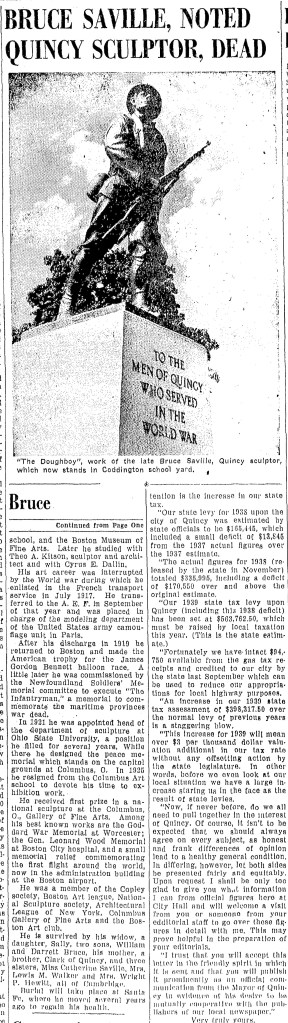

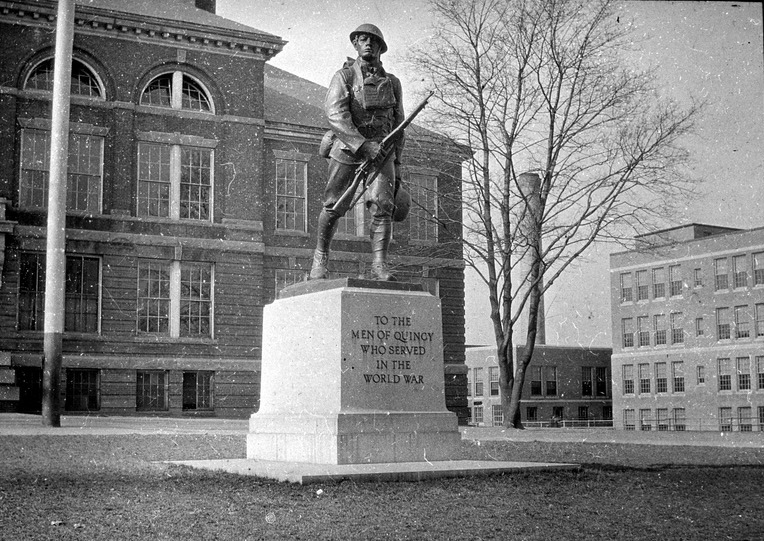

The Patriot Ledger hailed the memorial’s sculptor, Bruce Wilder Saville, as “One of Quincy’s most distinguished native sons.” Saville was best known in town for another of his works, the WWI “Doughboy” Memorial that stood in front of the Coddington School. The Quincy Historical Society included Saville’s obituary from the Patriot Ledger, which I’ll reproduce below, along with a photo of the Doughboy Memorial that the society sent me.

Another newspaper clipping revealed that the $5,000 memorial was a gift to the city of Quincy from the U.S. government. In 1961, city leaders voted to move the monument to the Adams birthplaces, but when the NPS took over management of the site 1979, the city returned the monument to Merrymount Park. I’ll reproduce a newspaper article related to that, as well (see below).

Every monument and memorial has a story of its own, and I find those stories fascinating. They can tell us a lot about the people they honor as well as the people who are doing the honoring.

Please consider supporting your own local historical society (and, if you’re so inclined, please consider supporting the Quincy Historical Society while you’re at it). Organizations like this provide invaluable services to researchers everywhere, but more importantly, they carry the torch for the history in your own back yard.