Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Evan Portman

Most historians credit Ann Pamela Cunningham with kickstarting the historic preservation movement with her purchase of Mount Vernon in 1858. However, preservation of historic sites began long before the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. In fact, the storied walls of Fort Ticonderoga became the object of a preservation movement 38 years before the Ladies’ Association purchased George Washington’s ancestral home.

Fort Ticonderoga—known as the Gibraltar of North America—played an integral role in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. The fort was originally constructed by the French in 1755 on a portage known to the Iroquois as ticonderoga, meaning a “land between two waters.” Fort Carillon, as it was known to the French, stood strategically between Lake Champlain and Lake George, thereby controlling both the Hudson River Valley and St. Lawrence River Valley. On July 8, 1758, an outnumbered French army successfully defended the fort against British forces in the bloodiest battle of the French and Indian War.[1] However, the following year British General Jeffery Amherst captured the fort and renamed it Fort Ticonderoga.[2]

By the American Revolution, the fort had fallen into disrepair but was still guarded by a small British garrison. In 1775, it was the scene of one of the most famous dramas in American history. On May 10, Col. Benedict Arnold and Col. Ethan Allen led a combined force of the Green Mountain Boys and Massachusetts and Connecticut militiamen across Lake Champlain to capture the fort. “Come out you old Rat!” Allen famously cried to the fort’s commander, Capt. William Delaplace, and demanded he surrender the garrison “in the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress.”[3] Delaplace agreed, and Ticonderoga quickly fell into American hands.

Gen. John Burgoyne’s British army recaptured the fort in the 1777 Saratoga Campaign. During that campaign, a small force of British and Hessian troops garrisoned the fort. However, they abandoned it following Burgoyne’s surrender. The fort was occasionally occupied by British raiding parties in the subsequent years of the Revolution, but its glory days were over.[4]

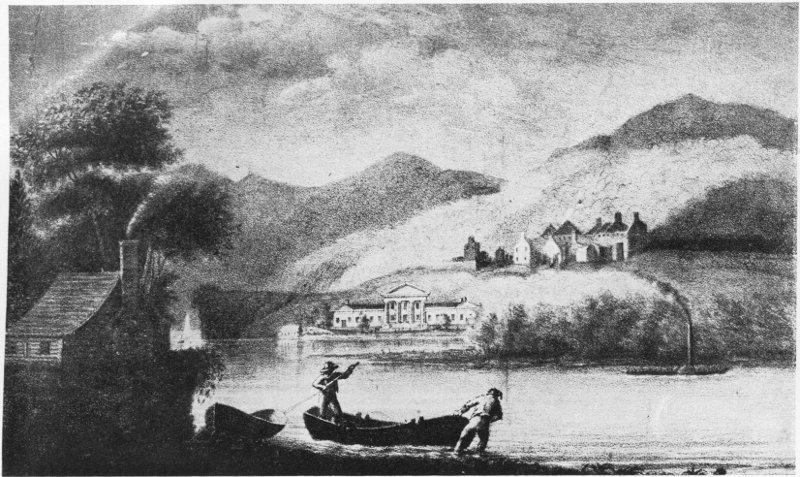

In the following decades, local residents stripped the crumbling fort of its stone, melted down its guns, and scavenged anything else they could use. In 1785, ownership of the fort passed to the state of New York, which donated the property to Columbia and Union Colleges in 1803.[5] Seventeen years later, the colleges sold the fort to William Ferris Pell, an American horticulturalist. Pell spotted the ruins of Fort Ticonderoga during a steamboat trip up Lake Champlain to Burlington, Vermont. In 1816, he began leasing the property from Columbia and Union Colleges, and in 1820 he bought the fort outright. Though Pell used the property to build his personal country estate (known as Pavilion) and did little to rebuild the fort itself, his purchase of Ticonderoga effectively saved it from further destruction.[6] He even protected the old French battle lines by building a fence around them and allowing trees and underbrush to grow around the earthworks, thereby preserving them.[7]

The ruins of the fort drew more tourists throughout the nineteenth century—so many that Pell decided to convert his Pavilion into a hotel. Hudson River School artists like Thomas Cole found their muse from the dramatic landscape surrounding the fort. Cole’s Ruins of Fort Ticonderoga became an influential early work for the artist. From the 1850s to the 1870s, social elite from across the country embarked on “the Northern tour,” taking them to the north country of New York, Vermont, and Massachusetts. Visitors arrived by steamer at the northern end of Lake George and boarded a carriage to Ticonderoga. They dined at Pavilion for lunch and then rode up the hill to tour the fort. Pell also maintained a lush garden, “abounding in the choicest fruits and plants imported from Europe and from the celebrated nurseries of Long Island,” that he used to feed his guests.[8]

In 1825, Pell’s son Archibald was killed in a cannon accident while firing a salute to his father who had just stepped off a boat. Grieving the loss of his favorite son, Pell vowed never to return to Ticonderoga. In his stead, various members of the Pell family took charge of Pavilion and the Ticonderoga ruins for the ensuing decades. However, by the turn of the century, organizations like the Ticonderoga Historical Society made several attempts to introduce Congressional legislation authorizing the preservation of the Fort Ticonderoga Garrison Grounds.

On September 2, 1908, the historical society organized a clambake for members of the Champlain Valley press corps. Stephen Hyatt Pell (William’s great-grandson) happened to be in attendance that day, and the event reawakened his childhood fascination with Fort Ticonderoga.[9] Pell had long been fascinated by the fort’s history. He and his brother played among the ruins on their family’s trips to visit his grandmother at Pavilion. Already part owner, Pell bought his co-heirs out in 1909 with the aim of restoring the fort to its former glory.

Pell immediately spoke to his father-in-law, Col. Robert Means Thomspon, who pledged $500,000 to reconstruct the fort. Restoration of the West Barracks began first in the spring of 1909 under the direction of New York City architect Alfred C. Bossom. At one point during the early stages of restoration, President William Howard Taft visited the fort, along with the ambassadors of France and England and the governors of New York and Vermont, to observe the progress.[10]

The work briefly halted during World War I. Even Ticonderoga’s owner Stephen Pell paused promotion of the fort and his pledged his services to the war effort, serving first in the French army then in the American ambulance corps. Pell’s wife, Sarah Gibbs Thompson Pell, managed the fort and surrounding property. In fact, she received so many curious visitors that she made the decision to “hire a full-time guide and charge sight-seers a small sum to pay his salary.”[11]

However, restoration quickly resumed after Pell returned home from the war in 1919.[12] As construction moved to the four outer bastions, workers “unearthed a very considerable quantity of cannon balls, picks, shovels, china and glass, [and] cutlery.”[13] Mr. and Mrs. Pell began collecting artifacts from various Revolutionary War descendants in addition to those found during the restoration work. This collection of artifacts served as the basis of the Fort Ticonderoga Association’s Museum, founded by Stephen and Sarah Pell in 1931.[14] Pell remained actively involved in maintaining the fort as President of the Fort Ticonderoga Association until his death in 1950, after which his son, John H. G. Pell, took his father’s place.[15] Fort Ticonderoga remains one of the most well-known sites associated with the American Revolution, thanks to the early preservation efforts of William Ferris Pell and determination of Stephen and Sarah Pell. “May the spirit of Fort Ticonderoga continue to preserve that union, that justice, that tranquility, that defense, that general welfare, that liberty and that prosperity,” said Sarah Pell in a 1936 CBS radio broadcast, “which the founders of our government set as worthy objectives of this nation.”[16] Countless visitors encounter that same “spirit of Fort Ticonderoga” today as a result of the Pell family’s efforts

[1] William R. Nester, The Epic Battles for Ticonderoga, 1758, (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2008), 7.

[2] Carroll Vincent Lonergan, Ticonderoga, Historic Portage, (Ticonderoga, NY: Fort Mount Hope Society Press, 1959), 56.

[3] Ethan Allen, Ethan Allen’s Narrative of the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga, and of His Captivity and Treatment by the British, (Burlington, VT: C. Goodrich & S.B. Nichols, 1849), 8.

[4] Lonergan, Ticonderoga, 122.

[5] Edward Hamilton, Fort Ticonderoga, Key to the Continent, (Boston: Little, Brown, 1964), 226.

[6] S.H. Pell, Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History, (Ticonderoga, NY: Fort Ticonderoga Museum, 1966), 95.

[7] Helen Ives Gilchrist, Fort Ticonderoga in History, (Ticonderoga, NY: Fort Ticonderoga Museum, 1924), 98.

[8] Gilchrist, Fort Ticonderoga in History, 98-99.

[9] Carl R. Crego, Postcard History Series: Fort Ticonderoga, (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 92.

[10] Pell, Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History, 100.

[11] Pell, Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History, 108.

[12] Gilchrist, Fort Ticonderoga in History, 99.

[13] Pell, Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History, 106.

[14] Pell, Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History, 111.

[15] Pell, Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History, 111.

[16] “A Patriotic Service: Sarah Pell’s Enduring Legacy,” Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Ticonderoga Association, https://www.fortticonderoga.org/learn-and-explore/a-patriotic-service-sarah-pells-enduring-legacy/.

If you are interested in reading about the American Revolution, you may like my recently published novel, “THE FAR CORNER OF THE FIELD.” It’s a work of historical fiction that covers, in accurate detail, the early years of the war and includes the battles of Bunker Hill, Hubbardton, and Bennington. The story is told from the perspectives of British soldiers and American militiamen. https://thefarcornerofthefield.com

LikeLike