Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Evan Portman

Two future presidents walk into a Catholic church.

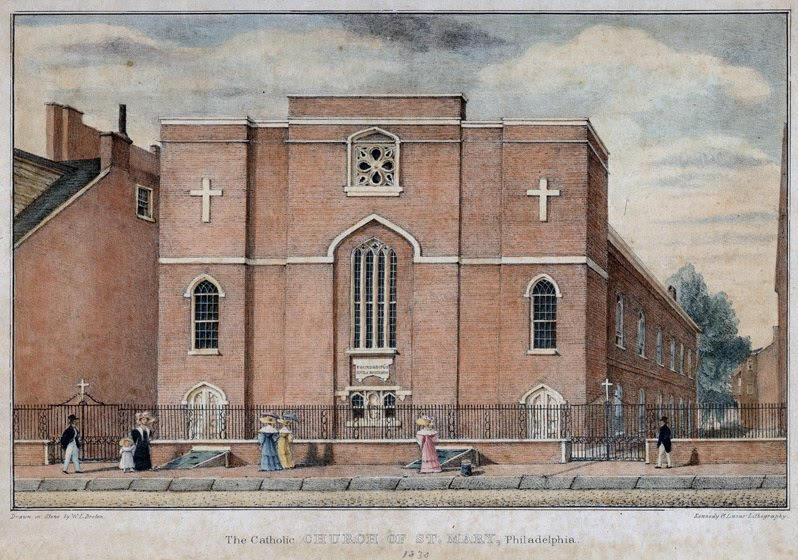

No, that’s not the beginning of a bad historical joke. It’s what happened on October 9, 1774, when George Washington and John Adams wandered into Old St. Mary’s Catholic Church while serving as delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

In September 1774, delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies convened in Philadelphia for the purpose of discussing a response to Parliament’s recent Intolerable Acts. But after a month of debating (and bickering), Adams wrote that “the Business of the Congress is tedious, beyond Expression.”[1] Seeking a break from the monotony, Adams and Washington ventured to one of the oldest Catholic churches in the colonies. Established in 1763 by parishioners of Old St. Joseph’s, St. Mary’s Church grew from the need for a Catholic cemetery.

“[L]ed by Curiosity and good Company I strolled away to Mother Church or rather Grandmother Church, I mean the Romish Chappell,” Adams wrote to his wife Abigail that day.[2] The church stood just a few blocks south of the Congress’s meeting place at Carpenters’ Hall and starkly contrast anything the Protestant Adams had seen before. A descendant of some of America’s early Puritans, Adams was raised in the Congregational church of Braintree, Massachusetts, where “unfettered daylight through clear window glass allowed for no dark or shadowed corners, no suggestion of mystery.”[3] Old St. Mary’s could not have been more different. Light poured through several stained-glass windows before a large, ornate altar, behind which hung a dramatic depiction of Christ’s passion while burning candles and incense lit the nave.

Adams’s puritanical upbringing taught him to abhor such pageantry in the house of the Lord. He looked with pity upon “the poor Wretches, fingering their Beads, chanting Latin, not a Word of which they understood, their Pater Nosters and Ave Maria’s.” Even “their holy Water—their Crossing themselves perpetually—their Bowing to the Name of Jesus, wherever they hear it” appalled the young lawyer from Boston.[4]

Despite his disdain, some elements of the mass impressed and even moved, Adams. He described the priest’s homily as a “good, short, moral Essay upon the Duty of Parents to their Children, founded in Justice and Charity, to take care of their Interests temporal and spiritual.” Its brevity stood in stark contrast to the long-winded sermons of the Great Awakening, with which Adams would likely have been familiar. Even the priest’s flashy garments were noteworthy to the future president. “The Dress of the Priest was rich with Lace—his Pulpit was Velvet and Gold,” Adams noted.[5]

But most noteworthy of all was the “Picture of our Saviour in a Frame of Marble over the Altar at full Length upon the Cross, in the Agonies, and the Blood dropping and streaming from his Wounds.” That combined with the organ music, which Adams described as “most sweetly and exquisitely” was enough to move him. “This Afternoons Entertainment was to me, most awfull and affecting,” he confessed. But in the eighteenth century, the word “awful” did not mean what it does today. Adams quite literally meant that he was “full of awe” in observing the mass. He was so moved, in fact, that he wondered how “Luther ever broke the spell” of Catholicism.[6]

Perhaps Adams’s experience that day, 250 years ago, is indicative of the Revolution at large, as it brought together men from disparate backgrounds and regions. As a young man in Braintree, Adams likely never imagined he could be moved by a “papist ceremony,” nor could he probably have imagined signing his name on a document securing independence from his former country. In this way, the American Revolution made fantasy a reality, and the impossible, possible.

[1]“John Adams to Abigail Adams, 9 October 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0111. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 166–167.]

[2] Ibid.

[3] David McCullough, John Adams, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 84.

[4] “John Adams to Abigail Adams, 9 October 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0111. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 166–167.]

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.