Due to a conflict in time with the Super Bowl this Sunday night, we will be moving the Rev War Revelry with Jack Kelly to a later date. We appreciate your understanding and will release a new date and time once confirmed. Thank you.

Author: William Griffith

Philip Livingston’s Grave, York, PA

While driving near York, Pennsylvania, I decided to stop by Prospect Hill Cemetery to visit the grave of Union General William Franklin. The cemetery was massive, and after locating Franklin’s grave and snapping a few photographs, I continued up the hill where I saw a plot devoted to dead Union soldiers who died while being treated at the army hospital located in York during the war. They were men from all throughout the North. Many of them simply having volunteered to fight, marched away from home, got sick, and died.

An older grave caught my eye just a stone’s throw away from the Civil War graves – a notable one that I did not know was in the cemetery. It was the grave of another non-Pennsylvanian. In fact, he was a New Yorker, and died in York in June of 1778, while a sitting member of the Continental Congress. It was the final resting place of a signer of the Declaration of Independence – Philip Livingston.

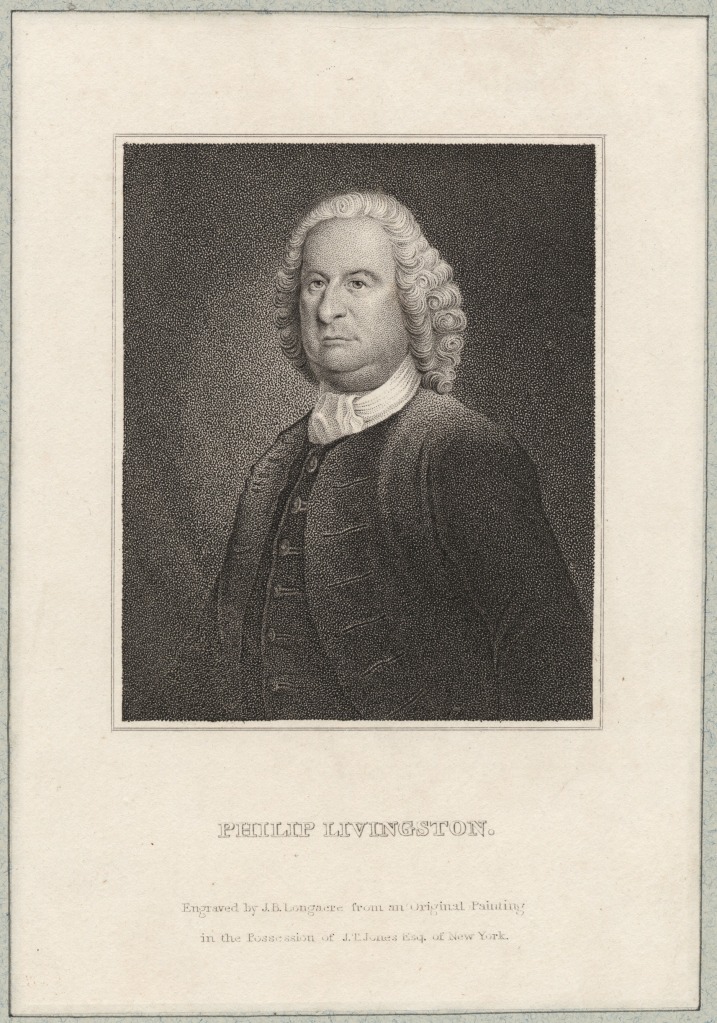

Philip Livingston certainly is not one of the Founding Fathers we remember. In fact, we probably remember his brother, William, who served as New Jersey’s Governor during the war, more. But Philip had a very impressive resume and played a part in nearly every major political conference in the colonies held in the years leading up to and during the early days of the American Revolution.

Born in 1716, Livingston graduated from Yale and pursued a career in the import business. Quickly, he built on his status and influence after relocating to Manhattan. He attended the Albany Congress in 1754, and was a member of the Stamp Act Congress, New York’s Committee of Safety, and president of the New York Provincial Congress in 1775. The prior year, Livingston was appointed to the First Continental Congress and was forced to flee his Manhattan home with his family when the British occupied the city in 1776. While he participated in the Second Continental Congress, he also served in the New York Senate.

Unfortunately, Livingston would never get to see his dream of an independent American nation become a reality. Following the British capture of Philadelphia in 1777, the Continental Congress relocated to York, Pennsylvania. Livingston had been suffering from dropsy, and his health was quickly deteriorating. He died suddenly in York while Congress was in session on June 12, 1778, and was laid to rest on Prospect Hill.

If you ever find yourself near York, take the time to visit the grave of a Founding Father who, far from home, died before the cause in which he pledged his life and sacred honor for could be won.

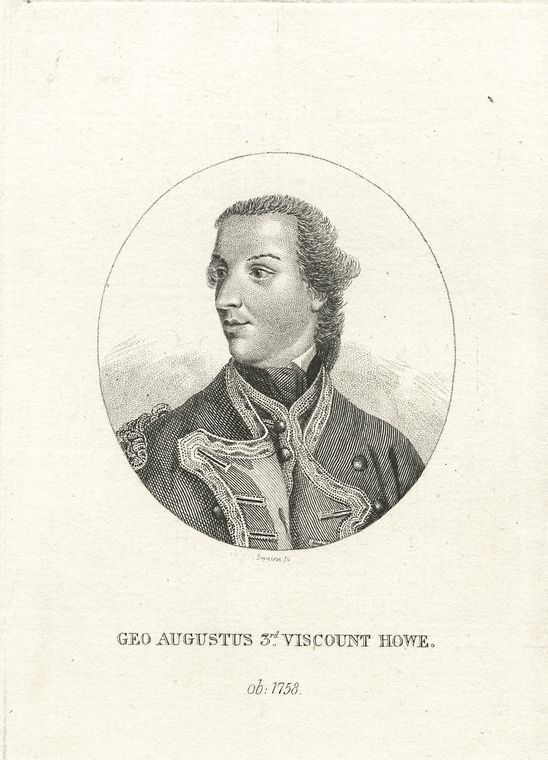

“The soul of General Abercromby’s army seemed to expire”: The Death of George Howe, July 6, 1758

They waded ashore during the morning of July 6, 1758. Full of confidence, the vanguard of Major General James Abercromby’s massive army of over 16,000 men had completed its nearly thirty-mile trek northward across the waters of Lake George. They began pushing inland – men from Thomas Gage’s 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot, Phineas Lyman’s 1st Connecticut Regiment, and of Robert Rogers’ famed rangers – scattering small pockets of French resistance. By early afternoon the entire army had debarked at the designated landing site and formed into four columns to begin its advance towards the primary objective: Fort Carillon. Moving forward into the thick wilderness with the rightmost column of mixed regular and provincial units was Abercromby’s second-in-command, Brigadier General George Howe. [1]

George Augustus, Third Viscount Howe, was born in Ireland in 1725. Like his younger brothers, Richard and William, George was destined for a career in His Majesty’s Forces and to serve in North America. His father, Emanuel Scrope, Second Viscount Howe, was a prominent member of parliament and served several years as the Royal Governor of Barbados before dying there of disease in 1735. Upon his father’s death, George assumed the title of Third Viscount and in 1745, at age twenty, was made an ensign in the 1st Foot Guards. Subsequently serving as an aide-de-camp to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, Howe fervently studied the strategies and tactics employed by his own commanding officers and the enemy, and witnessed firsthand the carnage of the War of Austrian Succession. Just ten years later, when the world was set ablaze by war yet again, George was ordered to Halifax, Nova Scotia with a commission as colonel of the 60th Regiment of Foot (Royal Americans) that was set to take part in a failed operation to capture Fortress Louisbourg in 1757. He was later made colonel of the 55th Regiment of Foot, and in December, appointed Brigadier General by William Pitt. The following summer, he accompanied the largest field army ever assembled in North America up to that time as its second-in-command. Continue reading ““The soul of General Abercromby’s army seemed to expire”: The Death of George Howe, July 6, 1758”

This Weekend’s Rev War Revelry: Arnold Along the James

Join us this Sunday, March 5, at 7:00 p.m. on our Facebook page for our latest installment of the Rev War Revelry series. This weekend’s chat will focus on the exploits of British General Benedict Arnold in Virginia during 1781, including the capture and burning of Richmond. We will be joined by Virginia historians John Pagano and Mark Wilcox, who will help bring to life the story of when Arnold turned his sword against the people he once called his comrades and countrymen. We hope to see you there!

“Fort Ticonderoga, the Last Campaigns” with Dr. Mark Edward Lender

During the War for Independence, Fort Ticonderoga’s guns, sited critically between Lakes Champlain and George, dominated north-south communications in upstate New York that were vital to both the British and American war efforts. In the public mind Ticonderoga was the “American Gibraltar” or the “Key to the Continent,” and patriots considered holding the fort essential to the success of the Revolutionary cause. Join us for this Sunday at 7 p.m. for the latest installment of our Rev War Revelry series as we welcome back award-winning historian, Dr. Mark Edward Lender, to discuss his newest book and the importance of Fort Ticonderoga in the oft-forgotten latter years of the Revolutionary War in Upstate New York.

The discussion will be held via Facebook Live on our page, https://www.facebook.com/emergingrevwar, and will be available afterwards on YouTube and Spotify.

Monmouth Monday: Centennial of the Battle of Monmouth, June 28, 1878

June 28, 1878, marked the centennial of the battle of Monmouth, and the anniversary did not pass without commemoration in the town of Freehold, New Jersey, the original location of Monmouth Courthouse. Local newspapers reported that over 20,000 people attended the various ceremonies, orations, and performances that were held, with local and state politicians, and veterans of the War of 1812, Mexican-American War, and the recent Civil War in attendance. George B. McClellan, former commanding general of the Union Armies and the Army of the Potomac, then serving as New Jersey’s governor, reviewed state troops and participated in the cornerstone laying of the Monmouth Battle Monument. The ceremony was the center of the commemorations that day. Although the 94-foot-tall monument crowned by a statue of “Colombia Triumphant,” would not be completed and dedicated until November 1884, those who attended the centennial events understood the significance of what it would represent. After all, it had only been thirteen years since the end of the previous war—one that was fought to save the republic that those who had bled at Monmouth fought themselves to establish. The symbolism was not lost on Enoch L. Cowart, a veteran of the 14th New Jersey Volunteers, which was trained at Camp Vredenburgh around the old battlefield. On July 4, 1878, an original poem he had written, “Centennial of the Battle of Monmouth,” was published in the Monmouth Democrat. Here is that poem below:

To visit the Monmouth Battle Monument and to walk the ground in which the fighting raged over in 1778, join Emerging Revolutionary War historians Billy Griffith and Phillip S. Greenwalt this November on a bus tour covering the winter encampment at Valley Forge and the Monmouth campaign. More information can be found on our website, http://www.emergingrevolutionarywar.org, or on our Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/events/632831987720200/?acontext=%7B%22event_action_history%22%3A%5B%7B%22surface%22%3A%22page%22%7D%5D%7D

267th Anniversary of the Battle of Lake George

Today marks the 267th anniversary of one of the first true “American military victories” during the 18th century: the battle of Lake George, New York. Fought just two months after Braddock’s Defeat along the Monongahela, William Johnson’s army of New Yorkers, New Englanders, and Mohawk warriors successfully halted a French advance that could have opened up the road to Albany. If you are unfamiliar with this key battle of the French and Indian War, check out our interviews below with the Lake George Battlefield Park Alliance, and ERW’s own Billy Griffith, the author of The Battle of Lake George: England’s First Triumph in the French and Indian War.

Braddock’s Defeat: An Evening with David L. Preston

On July 9, 1755, British regulars and American colonial troops under the command of General Edward Braddock, commander in chief of His Majesty’s Forces in North America, were attacked by French and Native American warriors shortly after crossing the Monongahela River while making their way to besiege Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley near modern-day Pittsburgh. The long line of red-coated troops struggled to maintain cohesion and discipline as Native American warriors quickly outflanked them and used the dense cover of the woods to masterful and lethal effect. Within hours, a powerful British army was routed, its commander mortally wounded, and two-thirds of its forces casualties in one the worst disasters in British military history.

Join us this Sunday evening at 7 p.m. for our latest Rev War Revelry as we sit down with historian David L. Preston to discuss his book and this critical event in America’s colonial history.

2022 Braddock Road Preservation Association Seminar

Our friends at the Braddock Road Preservation Association are pleased to announce that registration for their 2022 French and Indian War Symposium this November in Jumonville, PA, has officially opened. Below is the itinerary for the event which will include a bus tour and lectures by distinguished historians. If you would like to attend you can register at https://braddockroadpa.org/seminar/2022-seminar-registration/.

2022 SEMINAR SCHEDULE

The BRPA is returning to our pre-pandemic schedule and in person at Jumonville in 2022. We will offer an optional bus tour on Friday followed by an evening reception/program at Jumonville and a full schedule of presenters on Saturday. Optional lodging will again be available at Jumonville.

Friday – November 4, 2022

7:00 AM – Buses arrive at Jumonville

7:30 AM – Buses departs

– Friendly Fire site

– Westmoreland Museum of Art

– Braddock Battlefield Museum

– Fort Necessity National Battlefield

– Dunbar’s Camp

4:30 PM – Bus Tour Ends

Friday evening

6:00 pm – Optional Dinner at Jumonville

7:00 pm – Doors open for Wesley Hall Friday evening reception at Jumonville

7:30 pm – Dr. Jonathan Burns, Juniata College: “The Search for the 1758 Friendly Fire Incident Site at Ligonier”

Saturday – Nov. 5, 2022

8:00 am Registration – Coffee and Donuts

9:00 am Dr. David Preston, The Citadel: “Braddock’s Defeat and St. Clair’s Defeat: A Retrospective:

10:30 am Christian Fearer, Joint Chiefs of Staff, The Pentagon: “Those Loose, Idle, Self Willed and Ungovernable Persons: Virginia’s First Regiment”

12:30 pm Family Style Lunch (optional)

1:45 pm Martin West, Author and Historian: “Wielding the Club of Hercules: Benjamin West and the Painting of History”

3:15 pm Dr. Walter Powell, BRPA, Moderator: “The F&I War in Film and Literature: Some Highlights” Panel Discussion

5:00 pm Seminar Concludes

Lodging options at Jumonville are as follows

Rates below are per person and linens are included (no daily change in linen service)

(accommodations in the Inn – extremely limited availability)

Single Occupancy – $110/Thursday night $175/Friday night $135/Saturday night

Double Occupancy – $90/Thursday night $150/Friday night $115/Saturday night

(accommodations in Wash Lodge – available Thursday night – Saturday night)

Single Occupancy – $95/1 night $155/2 nights $200/3 nights

Double Occupancy or more – $75/1 night $120/2 nights $170/3 nights

2022 SEMINAR COST

Bus tour & seminar – $200/person

Friday bus tour only – $125/person

History seminar only – $100/person $35/student

Friday optional diner at Jumonville – $20/person

Saturday optional lunch at Jumonville – $12/person

The Conway Cabal and the Politics on the Road to Monmouth with Dr. Mark Edward Lender

Join us this Sunday night as we discuss the Conway Cabal with award winning historian Dr. Mark Edward Lender, author of Cabal! The Plot Against General Washington. We will discuss details of the “cabal” and the politics that impacted the events surrounding the battle of Monmouth and George Washington, himself.

This free Zoom event will begin at 7 p.m. and will be broadcasted live on our Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/emergingrevwar