In the aftermath of the April 19, 1775 fighting at Lexington, Concord, Menotomy, and the road back to Boston, militia swarmed from across New England to surround the British forces in Boston. With fighting now underway, a wave of enthusiasm swept through the region, with a decade of tension now broken by actual combat.

Continue reading “The Militia Myth”Category: Uncategorized

The Patriot Martyrs of April 19, 1775

Yesterday marked the 250th anniversary of the first battles of the American Revolution. The Battles of Lexington and Concord were brutal and vicious. More than 40 American colonists were killed in the fighting. These were the first martyrs in the cause for American liberty. Here are the stories of some of those men who shed their blood on that fateful day for our freedom.

Jonathan Harrington was one of the few dozen men in the Lexington militia who stood on the Lexington Green when the first British troops arrived at sunrise on April 19, 1775. He lived with his wife and child in a home that was located on the Green. After a shot was fired, the British soldiers opened fire on the American militiamen. As they were dispersing, Harrington was shot through the chest. He crawled towards his house and died within sight of his home. Local legend says he crawled to his own doorstep and died at the feet of his wife and child.

Isaac Davis was the captain of the Acton minutemen. The Acton minutemen marched more than 5 miles to Concord in the early morning hours of April 19. After seeing smoke from the town, the minutemen marched down towards the North Bridge and the British soldiers guarding the opposite side fired a volley at the minutemen. This volley was high and may have been a warning shot. The next volley was fired into the minutemen. Private Abner Hosmer was shot through the head and killed. Davis was shot through the chest, his blood splattering the men around him. Seconds later the American colonists were given the command to fire on British soldiers for the very first time.

James Hayward was part of the Acton company that joined in the running battle back towards Boston. During the battle soldiers from both sides stopped to get water at local wells. At one point a British soldier went to the well by the Fiske house to get a drink of water. At the same time, Hayward was heading there too. The two saw each other and raised their muskets. The British soldier said, “You are a dead man!” Hayward replied, “So are you.” They both fired at the same time. The British soldier was killed instantly. Hayward was hit, with splinters of his powder horn going into his side. He died not long after.

Jason Russell was a 58-year-old man living in the village of Metonomy (present day Arlington, Massachusetts) and was preparing to defend his home on the road back to Boston. People were telling him to leave the area, but Russell refused and exclaimed “An Englishman’s home is his castle!” As the British column came down the road, Russell and a dozen militiamen began to fire into redcoats. Unfortunately for Russell and the other militiamen, the British had deployed flankers to clear out many of the houses along the road. The colonists were taken by surprise and retreated into the house. Russell was unable to run and was bayonetted to death by the British troops on his front doorstep. The British entered the house and hand to hand fighting occurred inside the house. Two British soldiers and eleven militiamen were killed.

Jason Winship and Jabez Wyman decided to sit in the Cooper Tavern and have a drink. The fighting in Metonomy became extremely brutal. Even unarmed civilians got caught up in the carnage. As British arrived at the Cooper Tavern, the tavern owners fled into a cellar. Winship and Wyman did not stand a chance. The owners noted that: “the King’s regular troops under the command of General Gage, upon their return from blood and slaughter, which they had made at Lexington and Concord, fired more than one hundred bullets into the house where we dwell, through doors, and windows,…The two aged gentlemen [Winship and Wyman] were immediately most barbarously and inhumanly murdered by them, being stabbed through in many places, their heads mangled, skulls broke, and their brains out on the floor and walls of the house.”

Samuel Whittemore was a 78-year-old man who lived in Menotomy. He prepared to fight the British troops marching along the road. He carried a musket, two pistols and a sword. As some British soldiers moved to get Whittemore, he shot one with his musket, then killed two with his pistols and then drew his sword to fight them. The British soldiers shot off part of his face off, clubbed him and bayoneted him fourteen times, leaving him for dead. Amazingly, he survived and live for another eighteen years, dying at the ripe age of 96.

One of the last people to die that day was 65-year-old militiaman James Miller. As the British were making it back to Charlestown, James Miller and some men fired into the retreating soldiers. British soldiers ran towards the militia. Miller’s compatriots fled and entreated him to do the same. Miller replied, “I am too old to run.” The British opened fire and killed Miller.

These stories are only a few of the dozens who died that day. You can find these and many other stories (and where they happened!) in “A Single Blow” by Robert Orrison and Phill Greenwalt, one of seven books that are part of the Emerging Revolutionary War book series published by Savas Beatie.

Today the remains of the men who were killed on Lexington Green now lie there under a monument that was erected in 1799, not long after the successful conclusion of the Revolutionary War. The epitaph on that monument still speaks to the heroism and valor of these first Americans to fall in the Revolutionary War:

“The Blood of these Martyrs,

In the cause of God & their Country,

Was the Cement of the Union of these States, then

Colonies; & gave the spring to the spirit. Firmness

And resolution of their Fellow Citizens.

They rose as one man to revenge their brethren’s

Blood and at the point of the sword to assert &

Defend their native Rights.

They nobly dar’d to be free!!”

The Bloody Battle Road: Battle of Menotomy

ERW Welcomes Matt Beres, Executive Director of the Arlington Historical Society

On the morning of April 19, 1775, the first shot of America’s War for Independence was fired on the Lexington Green. Later that morning, Major John Buttrick, commanding the local Provincial forces, gave the order to fire on the British Regulars at the North Bridge. This act would later be remembered as the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” a phrase immortalized by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

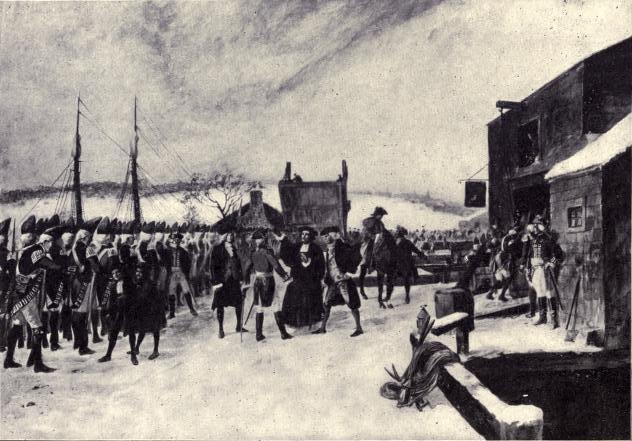

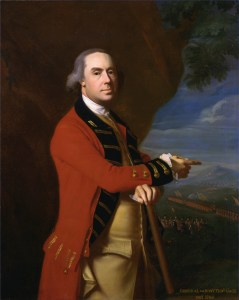

As Lt. Col. Smith’s British Regulars began their retreat back to Boston, Governor Thomas Gage sent a relief column of Regulars, led by General Hugh Percy. Meanwhile, Provincial militias and minute companies from surrounding towns marched toward the conflict, firing on both sides of the main road leading back to Boston. The Battle was just beginning.

While Lexington is famous as the site of the “first shot” and Concord for the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” Menotomy (present-day Arlington) is known as the site of the largest battle of the day, where fierce fighting erupted between the retreating British forces and the growing Provincial forces. The following stories are from this Battle.

David Lamson

Earlier that day, a convoy of provisions and supplies, protected by a detachment of British Regulars, arrived behind the main force heading toward Lexington and faced difficulties crossing the Brighton Bridge. Before their arrival, the Committee of Safety had removed the planks, and the combination of heavy wagons and repairs to the bridge caused the convoy to become separated from the main force, rendering it vulnerable.

An alarm rider from Cambridge alerted locals, prompting men from the ‘exempt’ or ‘alarm’ list—those unfit for regular Militia or Minute companies—to gather at Cooper’s Tavern to plan to capture the convoy. Among them was David Lamson, a biracial French and Indian War veteran, whose experience and bravery made him a natural leader. The group quickly appointed him as their Commanding Officer.

According to a story derived from Lamson himself, they positioned themselves behind a stone wall near the First Parish Meeting House. As the convoy approached, they ordered it to surrender. When the drivers urged their horses forward, Lamson’s men fired, killing the driver and several horses, and wounding two Regulars. In panic, the remaining six Regulars fled toward Spy Pond, and discarded their weapons.

It is said they then surrendered to an old woman, Mother Bathericke, who was in the field picking flowers. The old woman forced them to the house of Ephraim Frost, Captain of the Menotomy Militia, and stated, “… you tell King George that an old woman took six of his grenadiers prisoners.”

Samuel Whittemore

Around 4:00 pm, the retreating British Regulars arrived at the village Menotomy. It was here where Samuel Whittemore, the oldest known combatant of the Revolutionary War, earned his fame. During the conflict, Whittemore took cover behind a stone wall. He reportedly fired at five soldiers but was soon overwhelmed. He suffered a gunshot wound to the cheek and a bayonet stab wound. When the Regulars continued their retreat, the locals carried him to Cooper’s Tavern, where Dr. Tufts of Medford treated his injuries.

Remarkably, Whittemore survived for another 18 years after suffering these life-threatening wounds. He lived long enough to see the birth of a new and independent nation.

Jason Russell

Later during their retreat, Gen. Percy ordered his men to enter the residences along Concord Road (now Massachusetts Avenue) to eliminate the Provincials who were firing from inside these houses. One notable example was the site of Jason Russell House.

Jason Russell was a middle-aged farmer who reportedly had a leg disability. He barricaded his property and refused to leave, asserting, “An Englishman’s house is his castle.”

As British Regulars surrounded his home, several Provincials from different towns sought refuge inside. Tragically, Jason Russell and several others lost their lives on his property.

Today, the c. 1740 house, still bearing musket ball holes in the remaining structure from the fight, is at the heart of the Arlington Historical Society’s regional history museum, offering guided tours and engaging exhibits that highlight the lasting impacts of the American Revolution and Arlington’s broader history.

Explore more at: https://arlingtonhistorical.org/

Matt Beres

Executive Director

Arlington Historical Society

A Time for Conferences!

Students of the American Revolution face a wealth of opportunities at the end of May with two conferences in Virginia and New York. Although they overlap, they’re far enough apart geographically to cater to people from New England through the Mid-Atlantic down to the South.

National Museum of the United States Army Symposium

Events marking the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution are well underway and ERW is along for the ride to bring them to a wider audience. With that in mind, we’re pleased to draw attention to The National Museum of the United States Army, which is opening a new exhibit titled “Call to Arms: The Soldier and the Revolutionary War” and kicking off events with a Symposium on the war’s early years. (https://www.thenmusa.org/symposium2025/)

The Symposium starts virtually in the evening of May 29 with a panel discussion on commemoration before moving to both virtual and in-person talks on Friday, May 30. Panelists include:

- David Preston: “The Roots of Conflict.”

- Holly Mayer: “The Formation of the Continental Army.”

- Michael Cecere: “The Early was in the South.”

- Panel: “Revolutionary War Leadership,” with Christian McBurney, Joyce Lee Malcolm, and Ricardo Herrera.

- Mark Lender: “Washington’s Campaigns, 1776-1777.”

Those attending in-person will have a sneak peak at the “Call to Arms” exhibit. On May 31, John Maass will lead a group on a walking tour of George Washington’s Alexandria, Virginia.

The conference and walking tour are free, but do require registration as space is limited.

Fort Plain Museum and Historical Park Conference

The same weekend, Fort Plain Museum and Historical Park is holding its annual Revolutionary War Conference in Johnstown, NY with an equally auspicious lineup of speakers and presentations. Events begin with a bus tour of Lexington and Concord on May 29 and then recommence with a full series of speakers in the afternoon of May 30, all day on May 31, and a series of presentations on the morning of June 1.

Some of the featured speakers include Pulitzer Prize winning author Rick Atkinson, previewing his forthcoming book “The Fate of the Day: The War for America, Fort Ticonderoga to Charleston, 1777-1780,” Don Hagist discussing his groundbreaking work on British soldiers in the war, and Major General Jason Bohm, USMC (ret) on his book about the founding of the Marine Corps during the Revolution and its earliest operations.

Virginia 250th Events

Momentum for the 250th Anniversary is really picking up steam, as seen with recent special events in Virginia. On Sunday, March 23, St. John’s Church in Richmond observed the 250th anniversary of Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech.

The church held three reenactments of the meeting of the Second Virginia Convention, each sold out. In attendance at the 1:30 showing (thought to be about the time of the actual meeting), were filmmaker Ken Burns and Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin. Outside the church, reenactors greeted visitors, and representatives from several area historic sites had displays, including Mount Vernon, Wilton House Museum, Red Hill, the VA 250 Commission, Richmond National Battlefield Park, Tuckahoe Plantation, and the Virginia Museum of History and Culture. Mark Maloy, Rob Orrison, Mark Wilcox, and Bert Dunkerly of ERW were all present.

That afternoon park rangers from Richmond National Battlefield Park gave a special walking tour through the neighborhood focused on Henry’s speech and the concepts of liberty and citizenship through time.

That evening Richmond’s historic Altria Theater hosted the very first public premiere of Ken Burns’ new documentary, The American Revolution. A sellout crowd of over 3,000 saw snippets of the video, along with a panel discussion with Burns and several historians. The documentary will air nationwide starting on November 15.

Then, Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, Colonial Williamsburg hosted a gathering focused on 250th planning called, A Common Cause To All. The event featured about 600 representatives from historic sites, museums, and state 250 commissions. In all forty states were represented. Attendees discussed event planning, promotion, upcoming exhibits, educational opportunities, and more.

In his speech on March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry noted that “the next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms.” True enough, just a few weeks after his speech, word arrived of the fighting at Lexington and Concord. And soon, our readers will hear about the special events commemorating this anniversary in Massachusetts.

Rev War Revelry: Bravery and Sacrifice; Women of the Revolution in the Southern Campaign

Join us this Sunday at 7pm, for this pre-recorded Rev War Revelry where we chat with historian and author Robert Dunkerly about the role that women played in the Southern Campaigns. Most of us know about the story of Molly Pitcher but the women of the Southern Campaigns have been mostly over looked. Grab a drink and listen in as we uncover many untold stories and little known events that show the complexity of the American Revolution. The podcast will run on our Facebook page at 7pm on Sunday, March 16th. Then will be placed on our You Tube and Spotify channels.

“…there never was a more ridiculous expedition…” Oswego Raid 1783 – Part I

Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Eric Olsen. Eric is a historian with the National Park Service at Morristown National Historical Park. Click here for more information about the site.

Years ago, while I was looking at a list of disabled Revolutionary War veterans from Rhode Island I noticed some curious things. The list didn’t provide much information. It just gave the name and age of the veteran, their disability and how they were injured. At first, I was excited because I found a couple of guys who were wounded at the battle of Springfield in June 1780. But then I noticed a number of other men whose information seemed a little odd.

Several men were listed as having lost toes. Those same men had all lost their toes at a place called Oswego. Their wounds had all occurred in February 1783. A couple of the men even had the same unusual name of “Prince.” For me this raised several questions which required more research.

Where in the World is Oswego?

It turns out Oswego is a town in New York state on the eastern shore of Lake Ontario where it connects with the Oswego River. The name “Oswego” comes from the Iroquois word meaning “pouring out place” which is appropriate since it is where the Oswego River flows out into Lake Ontario. Heading inland, the Oswego River connects with the Oneida River which flows out of Oneida Lake.

In the 18th century lakes and rivers were the interstate highways of the day. Boats traveling on water could travel faster and carry heavier loads than wagons could on dirt roads. As a result, settlements developed along waterways and forts were built at strategic points where waterways connected.

The British originally established Oswego as a trading post on the northwest side of the mouth of the Oswego River. It was first fortified in 1727 and was known as the Fort of the Six Nations or Fort Oswego. By 1755 Fort Ontario was built on the opposite side of the river to bolster the area’s defenses during the French and Indian War. That fort was destroyed by the French in 1756 and rebuilt by the British in 1759. During the Revolutionary War, the fort was the starting point for St. Leger’s march against Fort Stanwix in 1777. Later the fort was abandoned by the British and destroyed by the Americans in 1778. The British returned and rebuilt the fort in 1782.

Continue reading ““…there never was a more ridiculous expedition…” Oswego Raid 1783 – Part I”William Washington, Hero of the Revolution

Stafford County, Virginia was the boyhood home to the most famous person in the Revolutionary War, George Washington. However, it was also the boyhood home for another, often overlooked, Washington. This was George Washington’s second cousin once removed, William Washington. William Washington was born and spent his early life in northern Stafford County and went on to become a war hero. He fought in many of the most important battles of the Revolutionary War and was wounded multiple times. For his valor in combat, he received a medal from the Continental Congress. After the war, he married and settled in Charleston, South Carolina where he became a planter and prominent state politician.

William Washington was born on February 28, 1752 at Windsor Forest plantation in Stafford County, Virginia. The 1200-acre plantation, no longer extant, is now part of the US Marine Corps Quantico Base, about a mile and a half north of present day Garrisonville Road. He was the second son of Bailey and Catherine Washington. The Washingtons were very active in the church and young William initially attended services at St. Paul’s in King George County and later attended services at Aquia Church in Stafford County. He was tutored by Rev. Dr. William Stuart and was preparing to enter the ministry. When not studying, Washington played, hunted, and rode horses throughout Stafford County. He was described by Henry Lee III as “possessed [of] a stout frame, being six feet high, broad, strong and corpulent.”

In the spring of 1775, William Washington left his studies to join in the Revolutionary War. He initially joined the Stafford minutemen and became the captain of that unit. In February 1776, William Washington was commissioned as one of ten company captains in the 3rd Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line. He was 23 years old. For the first part of 1776 the 3rd Virginia was stationed mostly around Williamsburg. By the end of July, they were ordered to march north and join George Washington’s main Continental Army outside of New York City. They marched north through Stafford County and stopped at the nearby James Hunter’s Iron Works to resupply.

Continue reading “William Washington, Hero of the Revolution”Call to Arms: The Soldier and the Revolutionary War Exhibit at the National Museum of the US Army

Join us this Washington’s Birthday (Observed) weekend on Sunday, February 16 at 7 p.m. EST on our Facebook page as we sit down with the curatorial staff of the National Museum of the United States Army to discuss the upcoming new special exhibition to commemorate the U.S. Army’s 250th birthday in 2025, and our nation’s declaration of independence in 2026. This new landmark exhibit will include a rare collection of Revolutionary War artifacts from the original colonies, England, France and Canada, accompanied by Soldier stories of our nation’s first veterans. Check out this preview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4vNXR3XWw9I

Can’t join us on Sunday? Check out the discussion later on our YouTube page or listen to the audio on our podcast! Emerging Revolutionary War is your home for America’s 250th!

“If you Fire, You’ll all be dead men” The Salem Alarm

We reshare a post from 2018 about the Salem Alarm also known as “Leslie’s Retreat.” As we approach the 250th anniversary of this important event (February 26, 1775), we will share primary source accounts of the event. This event set the kindling for the spark that lit a war in Lexington a month later.

As events quickly spiraled out of control in the winter and spring of 1774-1775 around Massachusetts, several armed confrontations between local “Patriots” and the British army heightened tensions. On many occasions, both sides adverted open confrontation and were able to diffuse the situation. Understanding these events and how they made an impression on both sides helps explain what happened on the Lexington Common on April 19, 1775.

As soon as British General Thomas Gage arrived in Boston in the spring of 1774, he set about enforcing the newly passed “Coercive Acts.” In response to these new laws that restricted many of the rights the people of Massachusetts had grown accustomed too, local groups began to arm themselves in opposition to British authority. Even though Gage was once popular in the colonies, he soon became an enemy to those around Boston who believed the Coercive Acts were an overstep of British authority. Continue reading ““If you Fire, You’ll all be dead men” The Salem Alarm”