Over the next few months, we will be highlighting the speakers and topic for our 2021 Symposium, Hindsight is 2020: Revisiting Misconceptions of the Revolution, taking place on May 22nd .

Today we continue with historian Vanessa Smiley who will be covering the myths and misconceptions of the Southern Campaigns during the American Revolution.

See Vanessa as she discusses an aspect of the Southern Campaign on March 7 at 7p.m. on Emerging Revolutionary War’s Facebook Live as part of the “Rev War Revelry” historian happy hour!

Vanessa Smiley is an historian and interpreter whose roots began at National Park Service Civil War and Rev War sites. Her Rev War park experience includes serving as the Chief of Interpretation at the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution Parks Group in South Carolina, an acting assignment as Superintendent at Guilford Courthouse NMP, and Chief of Interpretation at Morristown NHP. Vanessa is currently the Project Manager of Interpretive Media Development for the National Capital Area at Harpers Ferry Center. She received her undergraduate degree in Historic Preservation from the University of Mary Washington and her Master’s degree in Resource Interpretation from Stephen F. Austin State University.

Outside of her work with the NPS, Vanessa enjoys researching family histories, studying material and social culture of the 18th and 19th centuries, listening to podcasts, reading true crime, drinking craft beer, and attempting to make the perfect sangria. She and her husband live in Morgan County, West Virginia on their small farm where they run a nonprofit animal sanctuary.

She will be presenting her talk From the Bottom Up: Myths and Misconceptions of the Southern Theater at the May symposium.

Why do you believe the Southern Campaigns were so significant to the outcome of the American Revolution?

The simplest way to describe why I believe the Southern Campaigns were so significant to the War’s outcome is: it was a grassroots effort. What I mean is that while the Continental Army shouldered plenty, it was the combination of local efforts of the militia and determined civilians who turned the tide of the war when the British looked to the southern colonies, especially in the second half of the war. All one has to do is to look at two key battles, Kings Mountain and Cowpens, to see the impact of militia integrity, courage, and resolve.

Some point to the politics of Boston and New York as a driving force behind the start of the war. But the taverns and town halls of Charleston and Savannah were no less significant in adding fuel to the revolutionary fire. There is also the added dichotomy of our first true American civil war that played out in the backcountry of the Carolinas. Here were literal neighbors, brothers, cousins, and friends taking up arms to serve their respective causes and finding themselves on opposite sides. These dynamics were one driving force behind the militias that had such an impact during the Southern Campaigns.

What first attracted you to the study of early American history? What keeps you involved in the study of this history? Do you find these things are the same or different?

I give credit to my love of history to my high school history teacher, who embodied the archetype of the quintessential eccentric and genius history connoisseur striving to bring history alive. He immersed us in the history of the 18th and 19th century through first person accounts, visits to historical sites, and the dramatics of storytelling. He also armed me with the intellectual tool of piecing out the relevancy of events and people of the past, and that’s what has kept me interested in studying history for the past two decades.

While my work at historic sites for the National Park Service provided an easy outlet for my historian brain, I sought those historical connections and resources even outside of work because of that drive to understand the past. It’s a little bit different now than before though. I don’t get to be as immersed as I once was (no traipsing through cemeteries at night to feel the chill and terror of the Underground Railroad) and instead my mind goes to educating the public on the importance of our history. That’s why I’m so appreciative for Emerging Revolutionary War!

What is the biggest myth about the war in the South? How do you think it came about?

That the war was won in the north and not the south! I’ll go into more detail on this one during my presentation, but I’ll tease a little bit here. One part of the answer to the second question might lie with our public education system. In studying the state education curriculums of various states, I found that there is a stronger emphasis on the beginnings of the war than the war’s end. And so the Southern theater gets very little, if any, attention when kids study the war in school. The exception used to be in certain states like South Carolina, where the battles of Cowpens and Kings Mountain were directly referenced in the state standards. Since the standards updated in 2020, this no longer seems to be the case.

You’ll have to wait for my presentation to dive a little deeper into this myth with me!

Do you think there are common misconceptions of the era of the American Revolution among the American people? If so, what are they and have they ever affected your work?

There certainly are, and the ones that have affected my work the most center around that idea of the often-overlooked Southern Campaigns for most Americans. Ask any random person to name a Revolutionary War battle or event and the majority will name something from the northern colonies. Every now and then you get a Charleston, and if you consider Virginia part of the south, then a Yorktown for sure. But as I’m sure has become obvious already, I strive to educate about the rich history of the Rev War in the south.

Why do you think it is important for us to study the Revolutionary Era?

No matter which political, social, or economic side you’re on nowadays, we can all agree we are living in our own revolutionary time. And we find ourselves looking back to our nation’s founding for understanding and guidance, namely things like our national ideals and governmental processes. But we are a different people and a different nation than what we were then. We should not take everything from 240 years ago at face value. By studying and investigating the past, we can understand how and why decisions were made at the time. And perhaps we can extract an element, or life lesson, that can be applied to our modern times.

I believe that while history does not repeat itself, it does rhyme. By understanding the past, we may know our future.

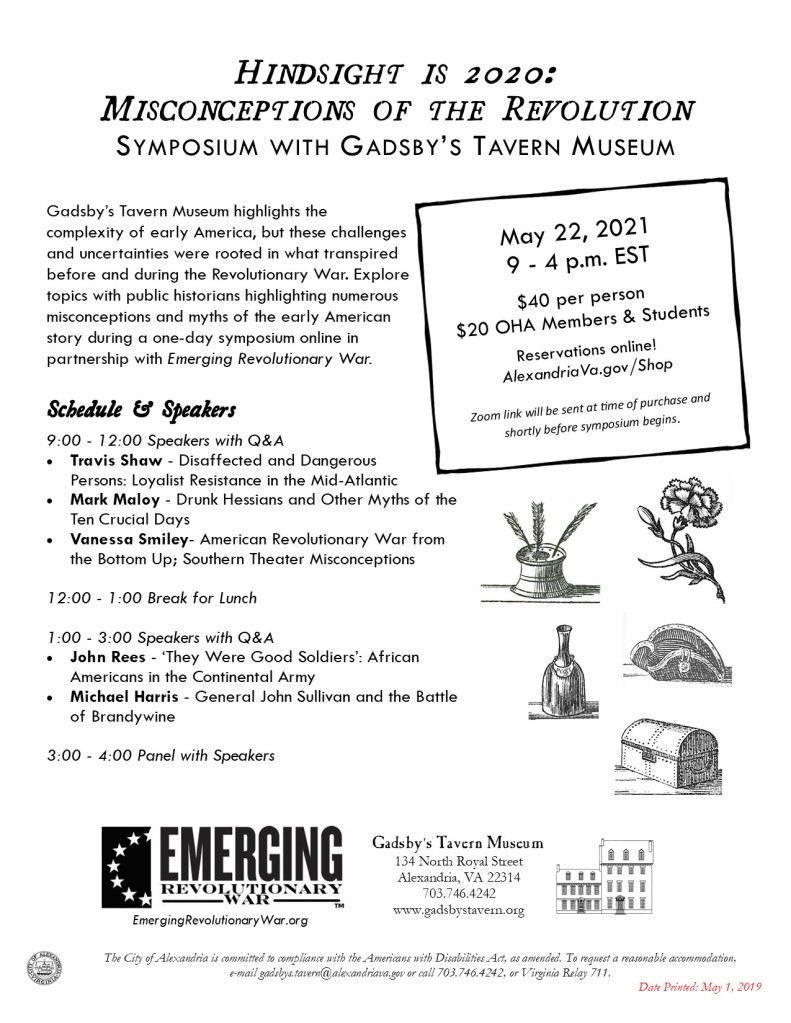

Join us for our SECOND annual Emerging Revolutionary War Symposium. Due to the COVID 19 pandemic, we postponed the 2020 Symposium to May 22, 2021 with the same topics and speakers. Co hosted by Gadsby’s Tavern Museum, speakers and topics include:

Michael Harris on Misconceptions of Battle of Brandywine

Vanessa Smiley on Myths of the Southern Campaigns

Travis Shaw on American Loyalists

John U Rees on African American Continental Soldiers

Mark Maloy on myths of the Battle of Trenton

Stay tuned as we highlight our speakers and their topics in future blog posts.

UPDATE: The 2021 Symposium will now be virtual. Though conditions with the pandemic are improving, we do not believe we will be able to have the event in person by May, so we have decided to be virtual. Due to this shift, we are also dropping the price! Now the full day symposium is $40 per person and $20 for students. This allows for guests from all across the country to learn about African American soldiers, Loyalists, and Drunken Hessians. Buy your ticket today!

To register visit: https://shop.alexandriava.gov/Events.aspx