Part II – Pennsylvania Line

Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian and park ranger Eric Olsen. Ranger Olsen works for the National Park Service at Morristown National Historical Park. Click here to learn more about the park.

What do poor health, a dead mother, a need to shop for new clothes, a pregnant wife, army business, a wife’s mental illness, family financial problems, and a desire to see family and old friends all have in common?

They are all reasons officers gave for asking for furloughs during the winter encampment of 1779-1780.

While the regulations and the various orders issued give us a general idea of the problems related to furloughs, we can get a different viewpoint by looking closer at the different Divisions, Brigades, and individuals who made up the army. The individual soldiers’ correspondence can also give us a more personal take on the furlough story. This paper will be far from comprehensive. It will just cover the furloughs that turn up in the surviving documentation. To make it easier to follow I have grouped the numbers and correspondence regarding furloughs by divisions and brigades.

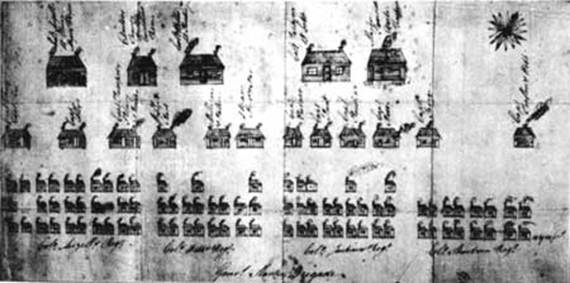

At the beginning of the winter encampment, a new division was created by combining the New York Brigade and Stark’s Brigade [below]. A note from mid-January 1780 indicates at that time Colonel Angell was the acting commandant of this division.

Stark’s Brigade

Stark’s Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General John Stark. The brigade included

Angell’s 2nd Rhode Island Regiment, Sherburne’s Connecticut Regiment, Webb’s Connecticut Regiment and Jackson’s Massachusetts Regiment. In December Stark’s Brigade had 1,023 men present and fit for duty. The monthly number of furloughs from the brigade’s rank and file were.

Stark’s Brigade Rank & File on Furlough

Nov. 1779 – 13

Dec. 1780 – 3

Jan. 1780 – 70

Feb. 1780 – 80

Mar. 1780 – 83

Apr. 1780 – 25

May 1780 – 12

Jun. 1780 – 6

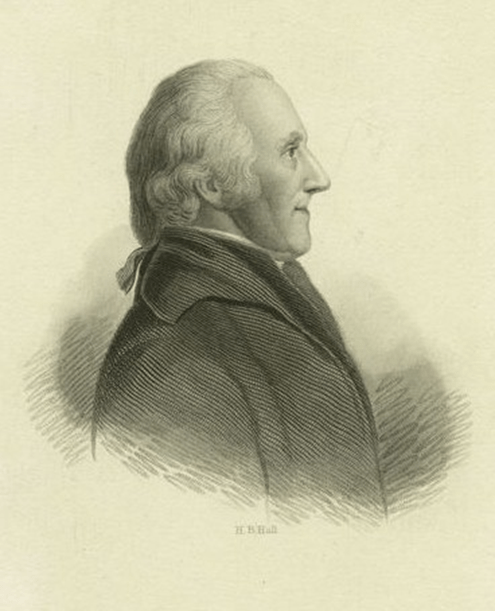

General Stark

Brigadier General John Stark, who commanded a brigade of New England regiments, had trouble getting a furlough that winter. Washington denied his furlough request on November 25, 1779, writing, “Your favor of the 22d for permission to be absent this Winter was handed to me this day. I should be very happy to grant your request but your continuance with the Troops at this time and while they are Hutting will be materially necessary and when that business is over, should the situation of affairs still render your stay requisite [indispensable], I hope you will cheerfully submit to the disappointment; [if] however you can be endulged with any degree of propriety you certainly shall.

General Stark [below] thought he would finally get away by mid-January but on January 14, 1780, Stark received the following disappointing note from Washington’s secretary Robert Hanson Harrison, “I have it in command from his Excellency to inform you that Colonel Jackson has represented to him, that you have discharged a soldier belonging to his Regiment contrary to the spirit and directions of his letter of the 6th Instant and the information you had received of his opinion on the inadmissibility of the Soldiers claims to discharges who were similarly circumstanced. And it is the Generals request that you will defer your journey ‘till you satisfy him on the point.”

Stark went to Washington the same day to explain his actions. While Washington was annoyed that Stark’s actions were “contrary to my sentiments” he replied the next day “it is by no means my wish to delay you from prosecuting your Journey to the eastward.” Presumably Stark left camp as quickly as possible to avoid any other delays.

Col. Henry Sherburne took over command of Stark’s Brigade in General Stark’s absence. Based on his correspondence, Stark probably did not return to the army until late May 1780.

Col. Sherburne

Colonel Sherburne’s command of Stark’s Brigade lasted until sometime in mid-February. On February 15, 1780, Colonel Israel Anell wrote in his diary, “Col. Sherburne Returnd from head quarters and informed me he had got Liberty to go to Rhode Island…” He was probably still on furlough a month later because Capt. Abijah Savage, was noted as being the acting commandant of Col. Henry Sherburne’s Additional Continental Regiment.

Lt. John Hubbart Col. Angell’s Rhode Island Regiment

Lieutenant John Hubbart overstayed his furlough. Then he added to his problems by accepting a dinner invitation from General Washington.

Col. Israel Angell explained the problem in an April 8, 1780, note to Washington, personally delivered by Lt. Hubbart. Col. Angell wrote, “Am sorry to have occasion to trouble your Excellency upon so disagreeable a matter, Lieutenant John Hubbart of my Regt. who will present you these lines, had a furlough granted him the 2nd of January last for Eighty days which expired the 21st of March past.”

Overstaying a furlough was not uncommon, but Hubbart compounded his problems by not returning to the regiment before a muster, which was the monthly accounting of the regiment. Angell continued, “The 3rd Instant the Regt. was mustered and inspected Lt. Hubbart was not returned at this time but Capt. Tew who had been at Morris Town that morning returned while the Regt. was on the Parade and informed me Lt. Hubbart had arrived in Town the Evening before and would be in Camp before the Regt. was dismissed upon which I altered the muster rolls and returned him present.:

But Hubbart did not return that day and the following day Angell sent a sergeant to look for Hubbart and present him with a “billet” [handwritten note] which said, “Sir, I am much surprised at your Absence from the Regt. as you must be sensible you have already overstaid your furlough a number of days yesterday the Regt. was mustered and inspected and upon Capt. Tew’s informing me that you was in Morris Town and would be in Camp before the troops was dismist the parade I returned you present, and upon receipt of this shall expect you will immediately join the Regt. otherwise I shall be under the disagreeable necessity of returning you absent without leave.”

The sergeant returned without Lt. Hubbart, but he brought a “billet” from him which stated,

“Sir I recd. Yours of Sergt. Hopkins & am sensible of your gratitude & indulgence at the same time beg leave to inform you I should have return’d yesterday but on receiving a billet from his Excellency to dine to day thought it as well to be here as at camp. (I confess my fault in not writing to you on my return) when Capt. Tew was here yesterday I expected to have seen him again & intended to return to camp in company with him but after receiving the invitation I wrote you a billet on the subject, but no opportunity offered to send it, give me leave to assure you I shall return as soon as possible after dinner.”

A dinner invitation from the Commander-in Chief was a pretty good excuse but even Hubbart admitted he should have informed Col. Angell what was happening. It sounds like some of the excuses I used to give when I was a teenager.

But Hubbart had screwed up. Angell explained that the following day, “the Officers were called upon to bring in their rolls and swear to them, which obliged us to alter the Inspection Return and Rolls once more, and return him [Hubbart] absent without leave between the hours of eleven and twelve AM Lt. Hubbart arrived in camp. I thought it my duty as he had conducted to order him in Arrest which was Imediately done.”

Colonel Angell was only following the regulations, but he felt bad for the young lieutenant and wrote to Washington, “But from Lt. Hubbart’s former conduct and his being sensible of his errors now am induced to believe that the fault he has now committed arose from inadvertence and not from a willfull breach of orders. Therefore having given a narration of the affair and admitted him bearer of the same if it be your Excellency’s pleasure to overlook the matter will withdraw the arrest but submit it wholely to your better judgement.”

It was a minor affair. Something Washington didn’t need to get too involved with, so he had his secretary Robert Hanson Harrison answer Angell. He wrote, “I am directed by his Excellency the Commander in Chief to inform you that having considered your representation with respect to the arrest of Lieutenant Hubbart and all circumstances prior and posterior to it, he is willing that he should be released from it.”

Ensign Thomas Russell, Sherburne’s Regiment & Gen. Stark’s Aide

Thomas Russell was an ensign in Sherburne’s Regiment but was appointed an aide-de-camp to his brigade commander, General John Stark in November 1779. He had his own “Catch 22” of furloughs. He explained the problem to General Washington in a letter on January 18, 1780.

“May it Please your Excellency, That I having Obtaind a Furlough from Brigadier General Stark dated the 10th Inst., since which I have been Arrested by Col. Sherburne for Defaming his Character…”

A Division Court Martial was scheduled for the following day but the witnesses he needed to support his case were all on furlough, including General Stark. None of the witnesses were scheduled to return until April 1st. Consequently, the court was dissolved until the witnesses returned. Russell then begged, “your Excelleny’s Liberty to go home till my Furlough expires which is the First of April next, at which time I now Pawn my Honour to Return unless Detained by Sickness.” To aid his case, Colonel Angell the temporary commander of the division [since Stark was on furlough] signed the following statement on Russell’s letter to Washington, “As I am Acquaintd with Mr Russell I do Recomend him to Your Excelleny for the liberty of Going on his Furlough.”

Once again this was a matter that Washington didn’t need to get bogged down in dealing with. Instead, he had his aide Tench Tilghman deal with it. Tilghman wrote to Colonel Sherburne that Russell couldn’t leave camp without Sherburne’s permission. There is no record what Colonel Sherburne decided, but since he had Russell arrested for “defaming his character” I doubt Russell got to leave.

Ensign Russell did not get his day in court until June 3, 1780. The General Orders of June 13, 1780, reported the following on the court’s decision, “Ensign Russel of Colonel Sherburne’s late regiment was tried for “Defaming Colonel Sherburne’s Character in Company by saying he was a damn’d liar and Rascal.”

The Court on mature consideration are of opinion that the Charge against Ensign Russel is not fully supported yet they are of opinion that the expressions Mr Russel made use of respecting Colonel Sherburne were highly indecent and illiberal more especially when used by an inferior officer respecting his superior, he being the Commanding officer of the particular regiment to which Ensign Russel belonged and that he is Guilty of a breach of the 5th Article 18th Section of the Rules and Articles of War and do sentence that Ensign Russel be Reprimanded in General Orders.

The Commander in Chief approves the opinion of the Court. The Expressions Mr. Russel used were diametrically contrary to the rules of good breeding in the first place and in the second entirely disrespectful considering the relative situation between him and Colonel Sherburne; and in this view the General cannot but consider his conduct to have been highly reprehensible He is released from his Arrest.”

Not much a punishment by our standards, but very embarrassing for officers who were concerned about their reputation. Ensign Russell went back to duties and continued to serve until January 1, 1781, when he left the army.

New York Brigade

The New York Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General James Clinton. The brigade included the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th regiments. In December the New York Brigade had 1,092 men present and fit for duty. The monthly number of furloughs from the brigade’s rank and file were.

New York Brigade Rank & File on Furlough

Nov. 1779 – 19

Dec. 1780 – 23

Jan. 1780 – 150

Feb. 1780 – 153

Mar. 1780 – 109

Apr. 1780 – 26

May 1780 – 8

Jun. 1780 – 5

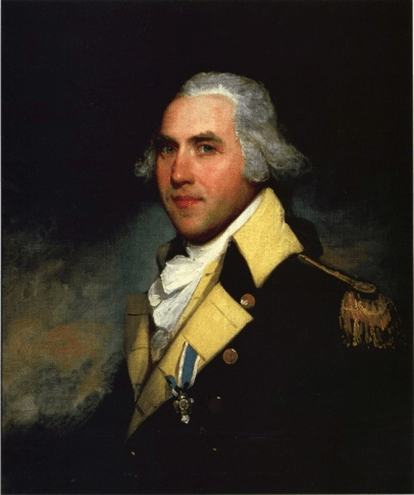

Brigadier General James Clinton

In late November 1779, after General Sullivan’s campaign against the Iroquois Nation, Brigadier General Clinton obtained a furlough from his superior Major General Sullivan. He needed to get home to care for his mother who was sick.

On January 14, 1780, Clinton wrote to General Washington requesting an extension to his furlough. He wrote, “I beg leave to inform your Excel. That in consequence of permission obtained of Gen. Sullivan I retired from the Army about the last of November to visit my Mother who was then dangerously ill and is since dead. This circumstance has rendered it necessary for me to continue at home longer than I at first intended. I would therefore presume to request a continuation of your Excell. Indulgence if constance with the good of the service until my family affairs are settled. I am encouraged to make this request as Col. Courtlandt commands theBrigade but if it should appear improper I shall hold myself in readiness to wait your Excellency’s commands on the shortest notice.”

Much to Clinton’s disappointment, Washington replied“I should have been glad had the situation of the Army, in respect to General Officers, admitted of my granting your request for a longer continuance of your furlough: But I am really obliged to dispense with many necessary Camp duties and to send Officers of inferior Ranks upon commands which ought in propriety to fall to General Officers. We have at this time but two Brigadiers of the line in Camp, and one of them, General Irvine has pressing calls to see his family and waits the return of you or General Huntington. You will see by the above that I am under the necessity of desiring you to join your Brigade as soon as you possibly can.”

General Clinton must have returned soon after getting Washington’s letter. General Irvine, who was waiting for Clinton’s return so he could go on his own furlough, was able to leave camp by early February.

ColonelGansevoort, 3rd New York Regiment

In late September at the end of General Sullivan’s campaign against the Iroquois Nations, Colonel Peter Gansevoort, [right] and his 3rd New York Regiment were detached to escort the baggage of the New York Brigade to Albany. But Gansevoort turned the job over to another officer. Gansevoort was sick and confined to his bed. According to his surgeon, he was suffering from Billious Fever.

His condition worsened. He wrote to his second in command, Marinus Willet on December 18, 1779, “Believe me I should not so long have neglected answering your letters if my indisposition had not prevented me. I have not yet been able to venture abroad since my relapse which attacked me so severe that my Physicians inform me they for some time despair’d of my recovery, and it has so weakened my sight that I am still incapable of reading or writing much…My state of health I fear will prevent my joining the Regiment this winter, however disagreeable this reflection is, it alleviates my distress when I consider that the command of the Regiment will be left with a person in whom I can confide.”

Willet replied to Gansevoort filling him in with news of the camp. He added a hint to his long absent commander in a postscript which said, “P.S. I suppose you have heard that absent officers are expected to join there corps by the first of April.”

Willet had wanted to take a furlough himself but was now filling in for his absent commander. On December 26, 1779, he reenforced his previous hint stating, “I hinted that all absent officers were ordered to join there respective corps by the first of April. I think it may not be amiss likewise to let you know, that there is an order for granting furlongs with an express direction that no Regt. is to be left without one Field officer, and that at least one officer with every company is to keep continually with the Regt. This being the case and it being my intention not to leave the Regt. during there continuence in Winter Quarters, or no. But as most of the captains & subalterns are desirous of leave of absence for some time during the stay of the troops in there present quarters, I think it may not be amiss to inform you that it is expected all the officers who are at present absent, will return to the regiment as soon as the time for which they had leave of absence expires, in order that the other officers may have an equal chance with them. I mention this least from understanding that all absent officers are ordered to join there respective corps by the first of April, you might be induced to lengthen the Furlongs of such of our officers who are in your quarter, which would be a disappointment to those officers now with the regt., most of whom expect leave of absence, on the return of such as are now abroad.”

Willet then added information asking Gansevoort to look for other New York officers in the Albany area who were expected to return to the winter camp. Then he once again added a veiled hint supposedly for the absent officers but probably also directed at Gansevoort which said, “It may not be amiss for absent officers to know that by a late resolve of Congress all officers who are absent from there regiments and ordered to join are liable to be tried by a Court Martial for noncompliance during there absence and cashiered. I flatter myself however that our officers will be as punctual as possible in complying with the terms of there furlongs – that no such disagreeable business may take place among us.”

Inspector General Steuben’s December 1779 report on the state of the army caused Washington much concern. There were problems in almost all the regiments. Washington sent letters to all his general’s demanding answers. One of the questions he posed to New York’s General Clinton about the New York Brigade concerned Col. Gansevoort. Washington asked, “What is the reason the Colonel himself has made so long a stay from his Regiment”

In turn General Clinton wrote to Gansevoort on February 12, 1780, “His Excellency Genl Washington he requests to know the reason… of your being so long absent yourself. I assure you he is much displeased with officers staying from their Regts and keeping soldiers as waiters with them, which is contrary to orders. If your health permits you to return with these men, pray do it without delay. Otherwise send the men.”

Col. Willet wrote again to Gansevoort about his absence on February 19, 1780, “Since my return from the lines [outpost duty]I have likewise been told enquiry was made by Genll Washington of the causes of your long absence, upon which I took the business upon myself and personally acquainted His Excellency of your long and severe illness. I have thought proper to write these matters to you lest Genll Clintons letter… should give you any uneasiness. And be assured that nothing in my power to promote the welfare of the regt shall be wanting during your absence.”

On March 7, 1780, Gansevoort wrote directly to Washington to defend his absence. He even included a doctor’s excuse. He stated, “It is with great concern I inform you that General Clinton has intimated to me in a letter that your Excellency is displeased with my long absence, give me leave to assure your Excellency that nothing but my indisposition has prevented me from joining the Regiment which I have the honor to command since my return from Seneca Country whence I was sent on command by General Sullivan. The certificate which I have the honor to inclose will manifest the assertion to which I beg to refer your Excellency…I beg leave however to add that I entered the service in the Summer of 1775, continued in it since and have never been charged with absenting myself from the Regiment to which I have belonged and believe _____that I should not have been absent at this time, if I had been able to have discharged my duty in the field, permit me to beg your Excellency’s Indulgence with leave of absence until my health shall be so far re-established as that I may be capable of doing the duty incident to my office.”

On the same day, Gansevoort also replied to Col. Willet. He again defended his absence, but unlike his letter to Washington he revealed he didn’t think he’d return until May. At this point Gansevoort had been away from the army for nearly 6 months. Gansevoort wrote, “I have done myself the honor of addressing a letter to his Excellency on the subject and transmitted him a Certificate from my Physicians declaratory of the reasons for my absence, to wit my indisposition of which I am now pretty well recovered but much doubt whether I shall be enabled to join the Regiment till about the first of May, as I cannot think of venturing it before I shall experience a perfect re-establishment of my health.”

Finally, Ensign Stephen Griffing, of the 4th NY Regiment wrote in his diary on May 15, 1780, “Col. Ganseworth [Gansevoort] arrived at Camp from Albany.” Colonel Peter Gansevoort had missed all but two weeks of the Morristown encampment and had been away from the army for almost 8 months.

Ensign Griffing, 4th New York Regiment

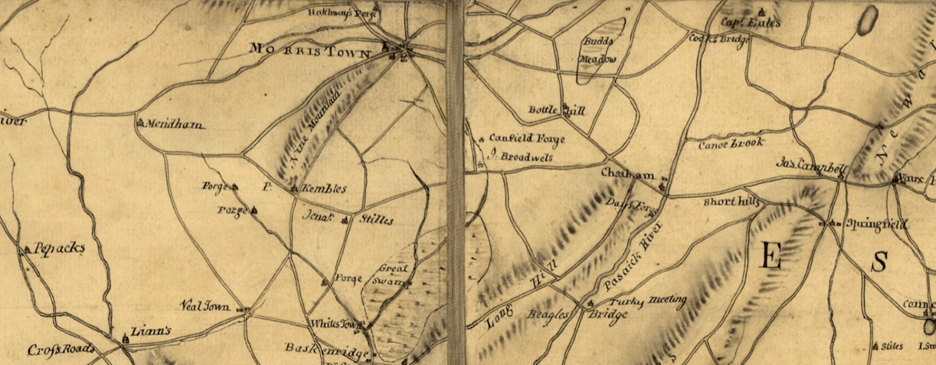

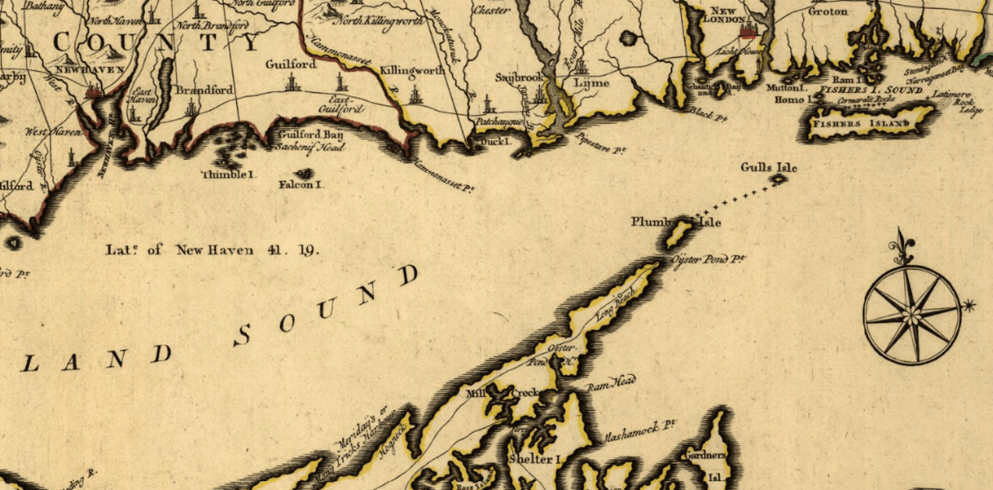

On November 10th, before the army arrived in Jockey Hollow, Ensign Stephen Griffing of the 4th New York Regiment got a furlough and left the army at Pompton, N.J. He walked from Pompton to Saybrook, Connecticut [map, top center] where he took a boat across Long Island Sound to “Acquabague” on the North Fork of Eastern Long Island [bottom center]. After spending four days on Long Island, he returned to Connecticut and eventually made his way to Morristown. He arrived at the camp in Jockey Hollow on January 25, after being away for two and a half months.

Ensign Barr, 4th New York Regiment

John Barr was another ensign in the 4th New York Regiment. Like the other soldiers of the New York Brigade, he had spent the summer of 1779 in the Finger Lakes Region of New as part of General Sullivan’s Indian Campaign. During the campaign in August Ensign Barr was sick for over a week. Then in September there was a 12-day break in his diary with no entries. But in the blank space he did insert a cure for venereal disease. Kind makes you wonder what was up. Whatever his malady was Barr still seemed to be able to march and take part in his camp duties.

Ensign Barr and his company reached Jockey Hollow and began building their huts on December 5, 1779. He and a couple of other officers moved into their hut on December 22nd. But two days later he moved out of camp writing, “moved to Mr. Saml. Broadwells about 5 miles from Camp to recover my Health, in Morris County three miles and a half from Morris Town.”

Broadwell lived east of Morristown and the camp [center of map below]. While at Broadwell’s house, Barr saw the troops heading east pass by his quarters on their way to the Staten Island raid.

On January 24, 1780, Ensign Barr left Mr. Broadwell’s and returned to camp. He wrote in his diary, “moved from Mr. Broadwells to Camp paid him Sixty Dollars for my Trouble 30 days.”

After he returned to camp, Barr took part in camp duties and Freemason meetings. But apparently, he was still suffering from some illness because on February 15th he wrote, “Left Camp on purpose to go home to the State of New York to recover my Health…” It took him a week of walking and riding to travel the 135 miles to reach his home in Dutchess County, New York. Barr made no reference to his health or mystery illness the entire time he was home on furlough. He didn’t return to the army until September 24th after an absence of 7 ½ months.

In his diary, Ensign Barr also mentioned furloughs of some of his fellow soldiers. Lieutenant Abraham Hyatt left on his furlough on November 11, 1779, and returned to camp on January 1, 1780 [51 days]. Ensign Azariah Tuthill left on a two-month furlough on January 5, 1780. Finally, Sergeants John Holly and Selah Brush both got 42-day furloughs on December 20, 1779.

Pingback: Morristown’s Individual Furlough Stories – Lord Stirling’s Division – Emerging Revolutionary War Era