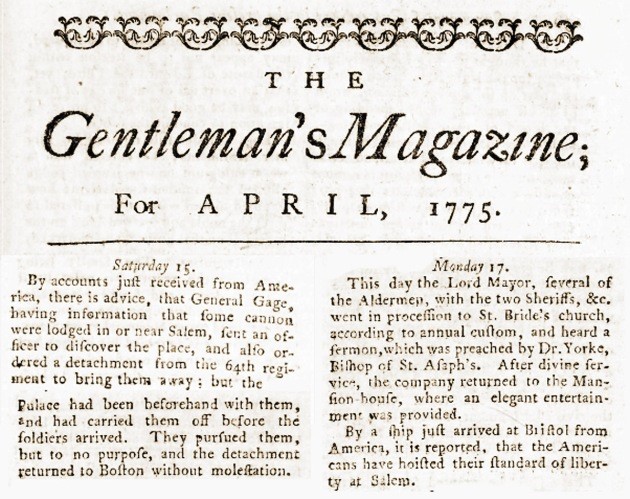

On Friday, April 21, 1775, word arrived in New Haven, Connecticut, regarding the fighting at Lexington and Concord. The Revolutionary War had begun, and thousands of militiamen from Massachusetts and the surrounding colonies in New England were converging around Boston to lay siege to the British army bottled up in the city. The next day, New Haven’s militia unit, the Governor’s Second Company of Guards, or Second Company, Governor’s Foot Guards, prepared to march to Cambridge.

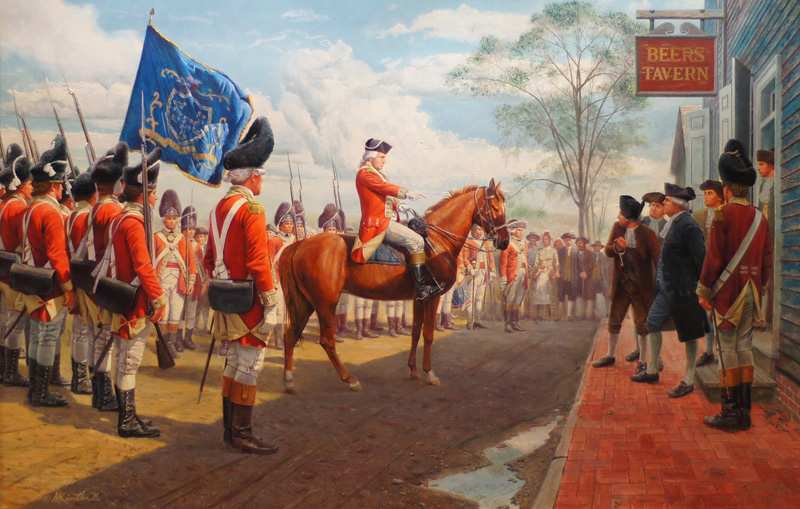

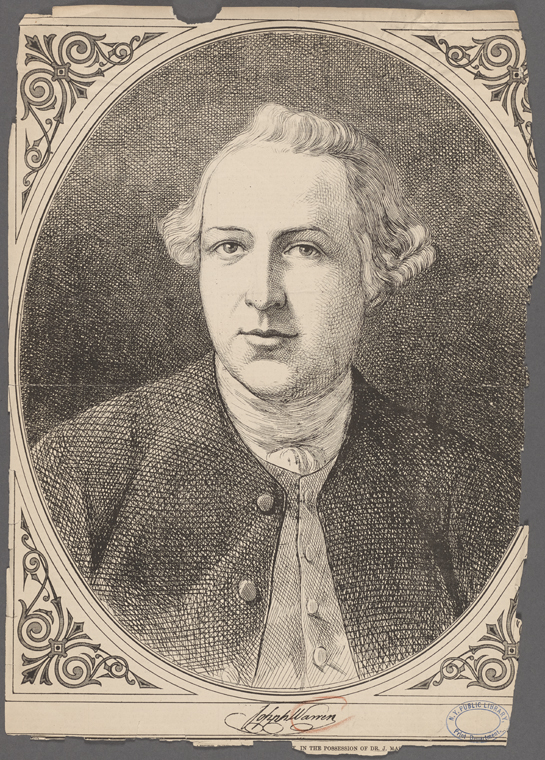

Garbed in “A scarlet coat of common length, the lapels, cuffs and collars of buff and trimmed with plain silver wash buttons, white linen vest, breeches and stockings, black half leggins and small, fashionable and narrow ruffled shirt,” the Foot Guards made for quite the appearance. At the head of the 65-man-strong company was Captain Benedict Arnold, a leading member in revolutionary New Haven.

Arnold, 34-years-old at the outbreak of the war, had not stood pat during the decade leading up to April 1775. He was a member of the Sons of Liberty, and on multiple occasions, led mobs against the pro-monarchy members of the community. His leadership and zeal were recognized in March 1775 when he was elected captain of the militia. Like so many other patriots throughout the colonies, the shots fired at Lexington and Concord on April 19 would catapult Arnold onto a path to glory, and unfortunately for the country, later treason.

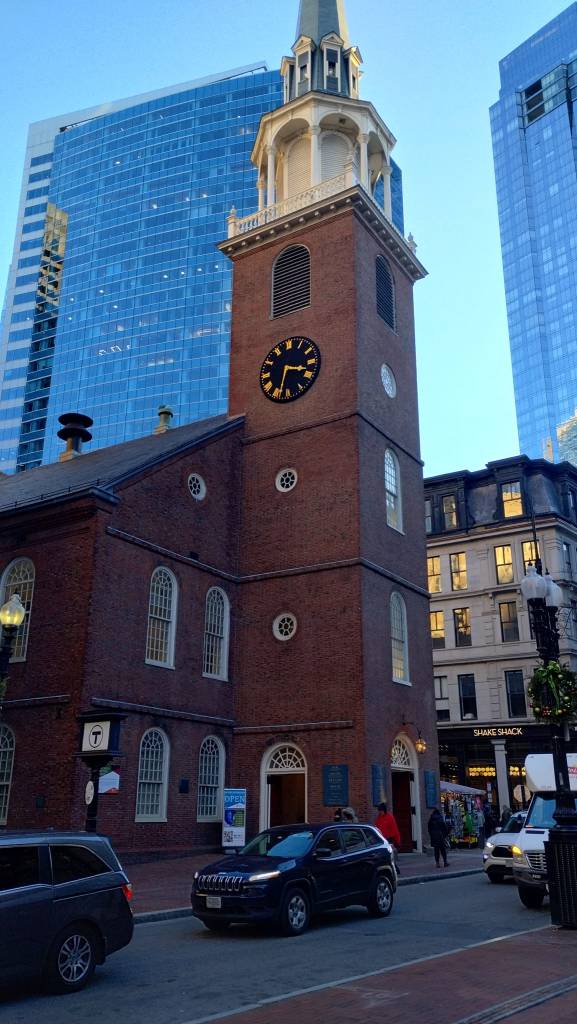

When the news arrived in town the evening of April 21, fifty-eight members of the Foot Guards voted to march to the assistance of their New England brethren. The next morning, Captain Arnold assembled the men on the New Haven Green, where the powder house was located. The doors were locked, and the keys to the stores in possession of New Haven’s Selectmen. Just off the green, at the intersection of College and Chapel Streets, stood Beers Tavern, where the Selectmen were gathered and discussing the town’s response to the recently received news.

The Foot Guards positioned themselves outside the building, while Arnold banged on the door demanding the keys to the powder house. The Selectmen refused to turn them over until official orders arrived. “None but the Almighty God shall prevent my marching,” Arnold passionately assured them. His forceful persuasion worked. The storehouse was opened, and the militia retrieved the necessary ammunition, flints, and powder. Once equipped, Arnold led his men out of New Haven and began a three-day march to Cambridge to join the fight.

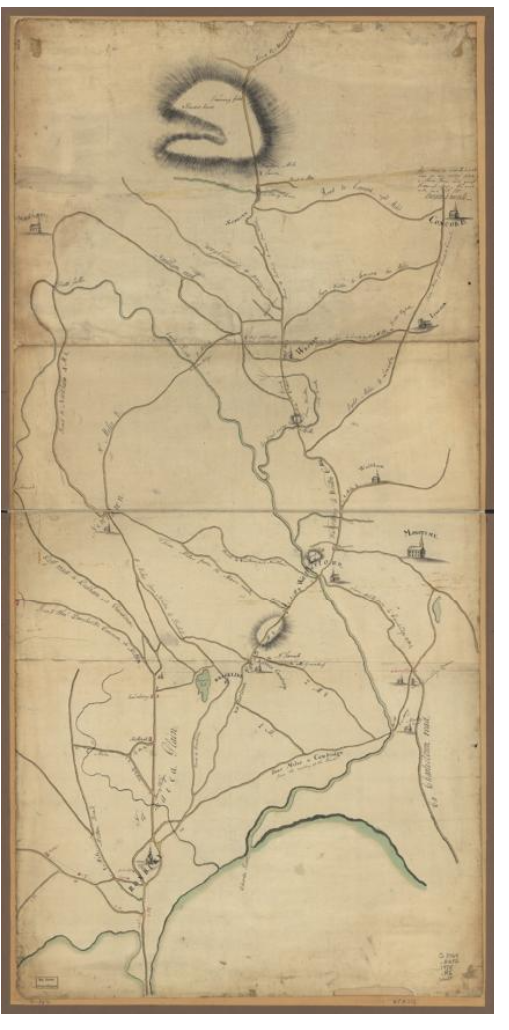

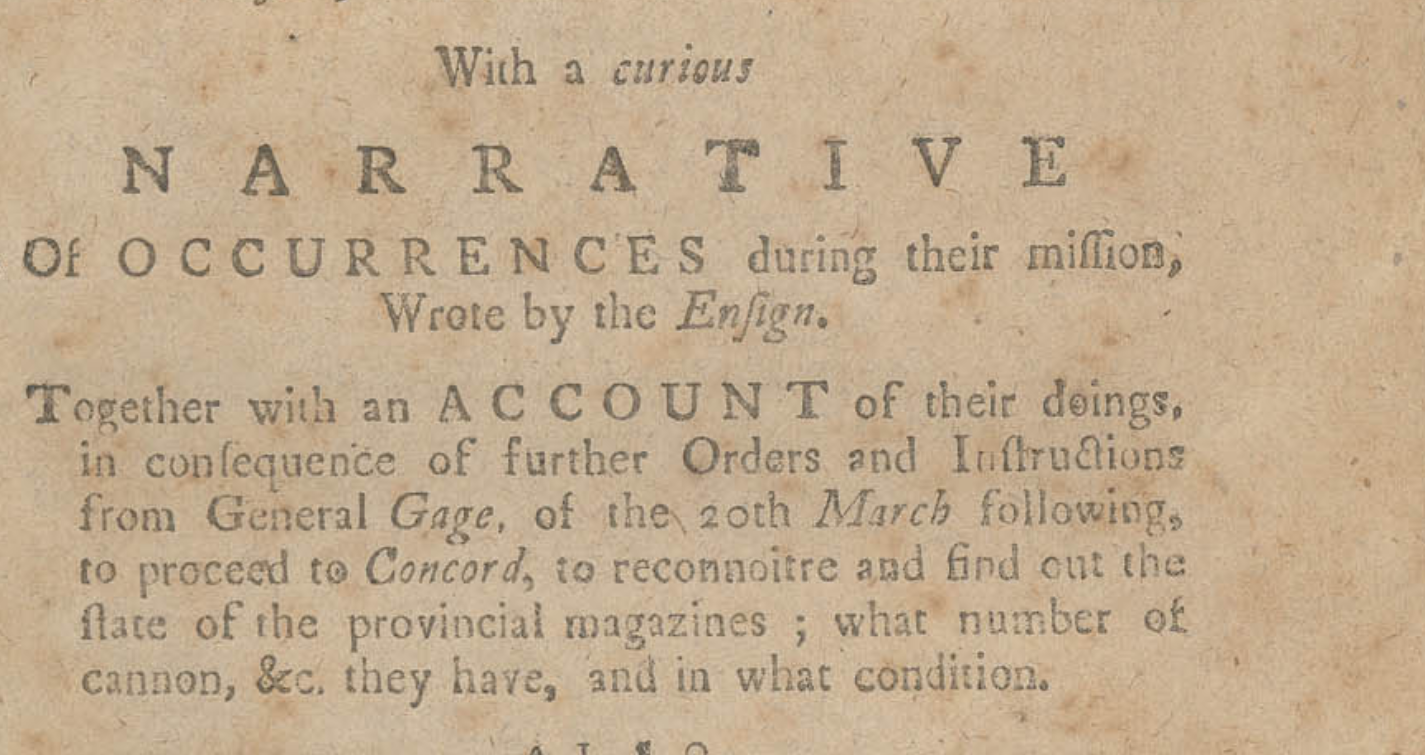

Idleness was not in Benedict Arnold’s nature, and upon arriving within the army’s camp, he approached the Massachusetts Committee of Safety with a proposal to lead an expedition against the British-held Ford Ticonderoga situated between Lake George and Lake Champlain in New York. The fort helped defend the crucial waterway system running north-south from Canada and housed cannon that could be vital to the patriot cause. The committee’s chairman, Dr. Joseph Warren, backed the plan and it was approved. On May 3, Arnold was promoted to colonel in the service of Massachusetts (not Connecticut) and was ordered to raise a force in western New England to accomplish the mission. The future hero of Saratoga and traitor to American liberty spurred his horse out of Cambridge and set his sights on taking “America’s Gibraltar.”