With three ships sitting at Griffins Wharf in Boston Harbor laden with tea, the Sons of Liberty were quickly running out of time on December 16, 1773. At the stroke of midnight, twenty days would have past since the first ship arrived in the harbor. At that time, customs officials would seize the cargo, the tax would be paid, and the British government would have been successful in forcing the colonists to pay a tax they did not consent to. The British would have demonstrated their power over the colonists. The colonists’ rights as Englishmen were at stake. Whereas the tea cosignees had resigned in New York and Philadelphia, the ones in Boston refused to resign and the Governor was refusing to allow the ships to leave the harbor.

On December 16, the leaders of Boston held a meeting they referred to as the “Body of the People.” Because of the large amount of interest in the issue, more than 5,000 people attended this meeting at the Old South Meeting House in Boston (the largest venue in the city). At the meeting was William Rotch, the owner of the ship Dartmouth which was the first ship to enter the harbor and would be the first to be seized by the customs officials on December 17. Rotch wanted to protect his property and see if the Governor would allow him to sail out of the harbor. The meeting recessed to let him go to the Governor outside of Boston and request the ability to leave the Harbor. Governor Hutchinson said he could not allow the Dartmouth to leave. After the meeting had reconvened in the Old South Meeting House, Rotch returned to Boston at about 6 p.m. and told the crowd that the Governor would not let the tea return. This news was responded to with loud cries and shouting.

At that moment, Samuel Adams declared “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.” After saying this, people heard Indian war whoops coming from the crowd and outside the building. Another person declared “Boston Harbor a teapot this night!” The people then began exiting the building and heading down to Griffins Wharf a few blocks away. Down at the wharf, men (some disguised as Mohawk Indians) began boarding the three ships. Approximately one hundred men boarded the ships and quickly got to work pulling up the large tea chests to the decks and dumping the tea into the cold water below. Crowds gathered and watched the men work for nearly two hours as they methodically worked to destroy all the tea on board the ships.

The men were careful to not destroy any other property except the tea. They also refused to steal any of the tea, punishing anyone who made an attempt. It was low tide and the tea started to pile up out of the water and needed to be mashed down into the water and mud.

British regulars were stationed at nearby Castle William, but they were not called down to the ships out of fear of insitigating a similar event as the Boston Massacre that occurred three years earlier. The British navy, posted in the harbor also made no attempt to stop the destruction. Some Royal Navy sailors watched the events on Griffins Wharf with some trepidation.

Once all 342 chests of tea had been tossed overboard, the destroyers left and the crowd dispersed. In all, they had destroyed 46 tons of tea on the ships.

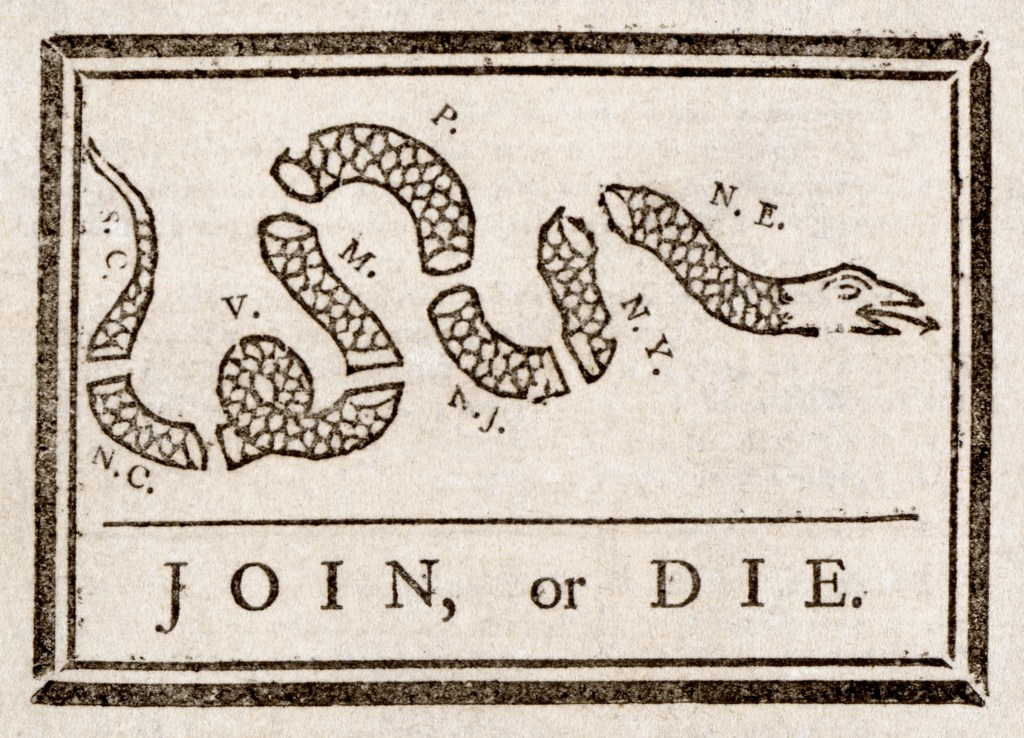

The event would have major repurcussions as the British determined to repsond to the event with brute force and would ultimately result in the Revolutionary War less than two years later. John Adams wrote: “This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cant but consider it as an Epocha in History.”

Learn more about the events happening to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party by visiting https://www.december16.org/.

You can learn more about Boston in the Revolutionary War by reading Rob Orrison and Phill Greenwalt’s book A Single Blow, part of the Emerging Revolutionary War book series.