If you follow Campaign 1776, the initiative by our friends at Civil War Trust, you are familiar with the saga over the Princeton Battlefield. Now you have a chance to help as well.

If you follow Campaign 1776, the initiative by our friends at Civil War Trust, you are familiar with the saga over the Princeton Battlefield. Now you have a chance to help as well.

With the start of the work week, some folks loath logging onto the computer to check work email, news, and updates. If you are one of those folks, keep reading, as the news we are about to share is positive and exciting.

This past Thursday, July 27, 2017, Campaign 1776, the initiative of the Civil War Trust, announced the preservation of 184 acres at two sites in New York state. One tract of land was pivotal to the United States success in the Saratoga Campaign in 1777 and where a U.S. fleet was saved during the War of 1812.

This past Thursday, July 27, 2017, Campaign 1776, the initiative of the Civil War Trust, announced the preservation of 184 acres at two sites in New York state. One tract of land was pivotal to the United States success in the Saratoga Campaign in 1777 and where a U.S. fleet was saved during the War of 1812.

The Battle of Fort Ann, fought on July 8, 1777 was a four-hour affair and was influential in the course of the larger Saratoga Campaign as it affected the British’s attempt to secure the strategically important Hudson River Valley. The delay around Fort Ann and every delay on the route of General John Burgoyne’s push south aided the Patriot cause tremendously.

Fast-forward to the War of 1812 and Sackets Harbor, New York provided as safe-haven for the United States fleet operating on the Great Lakes. Horse Island and the harbor that gained prominence during the May 29, 1813 offensive by the British, is where 24 acres were saved by Campaign 1776. The battlefield, which was one of 19 sites that benefited from $7.2 million in grants announced earlier in July and the first War of 1812 site anywhere in the country to be awarded money since the National Park Service expanded the grant opportunities in 2014.

Not just one success, but two for this Monday morning! For the full report, courtesy of our friends at Civil War Trust, click here.

For Part One, click here.

Lt. Col. Edmund Eyre’s battalion of 800 Regulars and Loyalists landed on the east bank of the Thames River, facing tangled woodlands and swamps. The New Jersey Loyalists, in fact, had so much difficulty moving the artillery that they did not participate in the assault on Fort Griswold.

Eyre sent a Captain Beckwith to the fort under a flag of truce to demand its surrender. Ledyard called a council of war and consulted with his officers. The Americans believed that a large force of militiamen would answer the call, and that this augmented force could defend the fort. Ledyard responded by sending an American flag to meet the British flag bearer. The American told Beckwith, “Colonel Ledyard will maintain the fort to its last extremity.” Displeased by the response, Eyre sent a second flag, threatening no quarter if the militia did not surrender. Ledyard gave the same response even though some of the Americans suggested that they should leave the fort and fight outside instead. Continue reading “Part Two: The Battle of Groton Heights, September 6, 1781: The Fort Griswold Massacre”

Part One

After turning coat, Benedict Arnold received a commission as a brigadier general in the British army as part of the deal that he made in order to betray his country.

In August 1781, George Washington decided to shift forces in order to attack the army of Lt. Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis in Virginia. Washington began pulling troops from the New York area. Lt. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander-in-chief in America, realized on September 2 that Washington’s tactics had deceived him, leaving him unable to mobilize quickly enough to help Cornwallis. Further, there was still a significant force of Continentals facing him in front of New York, and Clinton did not feel that he could detach troops to reinforce Cornwallis as a result.

Instead, Clinton decided to launch a raid into Connecticut in the hope of forcing Washington to respond. Clinton intended that this be a raid, but he also recognized that New London could be used as a permanent base of operations into the interior of New England. Clinton appointed Arnold to command the raid because he was from Connecticut and knew the terrain.

Instead, Clinton decided to launch a raid into Connecticut in the hope of forcing Washington to respond. Clinton intended that this be a raid, but he also recognized that New London could be used as a permanent base of operations into the interior of New England. Clinton appointed Arnold to command the raid because he was from Connecticut and knew the terrain.

Arnold commanded about 1,700 British solders, divided into two battalions. Lt. Col. Edmund Eyre commanded a battalion consisting of the 40th and 54th Regiments of Foot and Cortland Skinner’s New Jersey Volunteers, a Loyalist unit. Arnold himself commanded the other battalion, made up of the 38th Regiment of Foot and various Loyalist units, including the Loyal American Regiment and Arnold’s American Legion. Arnold also had about 100 Hessian Jägers, and three six-pound guns. This was a formidable force anchored by the three Regular regiments. Continue reading “The Battle of Groton Heights, September 6, 1781: The Fort Griswold Massacre”

In the quaint South Carolina town of Winnsboro, a few miles off of current Interstate-77 sites a two-story stands one of the oldest dwellings in a town founded by Richard Winn of Virginia a few years before the start of the American Revolution.

Yet, it was during those hostilities that one of the more famous military leaders came to “Winnsborough” as it was sometimes listed on maps of the time. His name, Lord Charles Cornwallis, the overall commander of British forces in the Southern Colonies. He would use the house during the winter of 1780-1781.

The house itself is an enigma. The structure dates to pre-1776 obviously, but the builder and owner of the house is still not known. Yet, it is well document that the house did serve during the labeled “winter of discontent” for the British and Cornwallis.

Across the street resides the Mount Zion Institute which became quarters for British soldiers during that winter of 1780-1781.

After the conflict the property and house was deeded to Captain John Buchanan, a veteran of the American Revolution. Buchanan was part of the welcoming party for the Marquis de Lafayette when the Frenchman landed at Georgetown, South Carolina.

Although not open to the public, special requests will be entertained. Click here for the link below for more information on the house and also who to contact for those special arrangements.

On April 19, 2017, symbolic in American Revolutionary War history, the Museum of the American Revolution opened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The weekend before, I had the chance, to get a “sneak peak” of the new museum.

I left thoroughly impressed as the museum fills in a critical need for telling this utmost important era in our nation’s history. Yet, the development of exhibits along with the myriad of learning styles and technology underscores the need in this 21st century to be approachable and inclusive to reach various levels of interest that the visitor may have.

Greeting visitors as they approach are a few murals depicting well-known scenes of the American Revolution–including the symbolic “Crossing of the Delaware” and the “Signing of the Declaration of the Declaration.” Along with one of the most important sections of the Declaration of Independence.

After entering the museum the exhibit area is on the second floor, beginning with the build-up to the war and ending with a nod to the upholding of the revolutionary ideals. Broken up into four segments, the exhibits cover the period of the “Road to Independence” from 1760-1775, “The Darkest Hour” 1776-1778, “A Revolutionary War” 1778-1783, and ending with “A New Nation” 1783 to present-day. A must-see is the short 15-minute film that is centered on George Washington’s command tent, which is shown behind the screen at the conclusion of the film.

Yet, do not shirk the exhibits, which include the a portion of the last remaining “Liberty Tree” from Annapolis, Maryland that fell during a hurricane a few years back. Small movie theaters dot the exhibit area depicting different aspects of the war and history. The Oneida Native Americans, the first allies of the United States are also prominently–and rightfully–highlighted as to their contributions.

Another of the interesting components of the museum is the use of interpretive questions, including “Why were they called Hessians?” with an accompanying multi-dimensional map that shows the different German principalities that contributed troops to the British war effort. Another interesting panel discusses the first use of acronym “USA.”

Another of the interesting components of the museum is the use of interpretive questions, including “Why were they called Hessians?” with an accompanying multi-dimensional map that shows the different German principalities that contributed troops to the British war effort. Another interesting panel discusses the first use of acronym “USA.”

The museum’s display collection of artifacts is also truly amazing. From a few of the first flags carried by units in the war, to the aforementioned “Liberty Tree”, to a portion of the famous North Bridge, in Concord, Massachusetts.

Combined with the interactive displays, the chance to walk onto a privateer ship, and the assortment of artifacts on display, the museum exhibit area caters to all levels of enthusiasts and can definitely absorb a few hours of your time.

With the museum main attractions situated on the second floor, the first floor of the museum is free to house the orientation film, a cafe, and the gift shop. If you have never been to Philadelphia, the museum is another highlight to add to your bucket list itinerary. If you have ventured to the “City of Brotherly Love” before, the museum provides an excellent reason to journey back.

For information on the museum, including programs, exhibits, and the admission fee, click here.

Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back guest historian Malanna Henderson

Part One

“It is not for their own land they fought, not even for a land which had adopted them, but for a land which had enslaved them, and whose laws, even in freedom, oftener oppressed than protected. Bravery, under such circumstances, has a peculiar beauty and merit.” – Harriet Beecher Stowe.

The words spoken by “the little woman who wrote the book that started this Great War,” so said Abraham Lincoln, according to legend, upon meeting Mrs. Stowe sometime in 1862, rang true for black patriots in the Civil War as well as those in the Revolutionary War.

The Smithsonian tome, The American Revolutionary War: A Visual History quotes a Hessian officer in 1777, as saying, “No regiment is to be seen in which there are not Negroes in abundance and among them are able-bodied and strong fellows.”

In every battle of the Revolutionary War from Lexington to Yorktown; black men, slave and free, picked up the musket and defended America; and yet, many historians as well as visual artists have omitted their contributions in the history books and their images on canvases depicting historic battles. The need for white historians to “overlook,” “underestimate,” and or “erase,” these sacrifices is a gross negligence that distorts and misrepresents American history; and furthermore, it continues to disenfranchise the patriotic heroes of the past and malign the self-image of millions of Americans today simply because of the color of their skin.

Black soldiers have always fought two wars simultaneously; wars declared by their government and the unspoken wars at home for liberty, equality and before the Civil War, for citizenship.

What kind of men fight for the liberty of others when their own liberty isn’t guaranteed?

True patriots: James Armistead Lafayette was one such person.

Slaves serving in the rebel military was a question that manifested itself early amongst the colonial government agencies. Their presence rankled many, while others welcomed them and praised their bravery. Some men of color had fought gallantly and with distinction as they stood alongside their white compatriots, defenders of liberty on the Lexington Green in April of 1775.

For instance, in the Battle of Bunker Hill, Peter Salem, a slave, served with courage under fire, as varying accounts reported. Salem was introduced to George Washington as “the man who shot Pitcairn,” the British Royal Marine Major who shouted to his men before Salem shot him down, “The day is ours.” Despite the competence and bravery of such men on the battlefield their exploits didn’t convert the wide-spread reluctance of most colonists to accept black men as soldiers.

General George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, harbored the same common prejudices of the southern-planter ruling class of which he was a member. In July, he instructed recruiters “not to enlist any stroller, negro, or vagabond, or person suspected of being an enemy to the liberty of America.” Commanders in each colony and regiment made up their own minds. Some ignored his command. Their decision was based on need and experience. Those who had already served successfully with black militia and minutemen may have seen no cause to alter their regiments.

By December of 1776, Washington back-pedaled on his decision, allowing for black veterans of Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill to serve; but of the slave, he maintained his objection. However, some junior officers appreciated the contributions of blacks. Col. John Thomas wrote John Adams on October 24, 1775, “We have negroes, but I look upon them as equally serviceable with other men, for fatigue (labor); and, in action many of them have proven themselves brave.”

As the war raged on, the necessity for able-bodied men settled the question. White soldiers, who usually served for only a few months to a year, mustered out, died or were wounded; while others deserted. Black soldiers who expected to receive their freedom if they served were in the war for the duration. This was a positive factor for the commanding officers who had to re-train all new recruits. Around five-thousand blacks served in the Revolutionary War as soldiers. However, a vast unknown number provided a myriad of support services.

Another reason the colonials reconsidered enlisting blacks was the bold military tactic that occurred in November of 1775. Lord Dunmore, the last royal governor of Virginia, ratified a proclamation freeing all indentured servants and slaves of rebels if they would fight for the British. Thousands of people fled the plantations to gain their freedom. This single act struck a devastating blow on two fronts, it threaten their economic stability and increased the tension between master and slave, with the master fearing slave revolts and the permanent loss of their property. Moreover, it upset the social order. Enslaved men serving alongside whites put them on an equal footing in the battlefield, which violated the white supremacy dogma that governed current thought and practice.

Born into slavery on December 10, 1748, in New Kent, Virginia to owner William Armistead, James enlisted in the Revolutionary War under General Marquis de Lafayette in 1781. His owner was a patriot and most likely received the bonus James would have gotten for enlisting had he been free or white. Enlistment bonuses comprised of money, land or slaves.

By the time Armistead entered the war, the efforts of Benjamin Franklin and other colonial agents had secured a military and economic alliance with the French. A long-time imperial rival of British expansion, the French provided naval ships, money and personnel.

Marquis de Lafayette (born Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier) was a descendant of ancient French nobility. His father, a colonel in the French Grenadiers had died in the Seven Year’s War (known as the French and Indian War in America) when the young nobleman was only two years old. The political ideals of liberty and equality espoused by the colonials matched his beliefs and fired his military ambitions. Perchance, his yearning to play a role in America’s fight for independence from British rule may have been spawned by a desire to avenge his father’s death.

Since Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, it was easy for Armistead to gain access in the enemy camps as a runaway slave seeking his freedom. While providing varied services to the British, he gained the confidence of Brigadier General Benedict Arnold, who by now had defected to the British. He charged Armistead with scouting, foraging and spying. Armistead was able to comfortably go between both camps, in essence becoming a double spy. He carried false and misleading information to the British but provided accurate intelligence on the movement of British forces and details of their military strategies to General Lafayette.

When Arnold left Virginia, Armistead was able to deceive General Charles Cornwallis as well, who rampaged through parts of Virginia and burned Richmond, the capital. He sent Colonel Banastre Tarleton to capture the entire legislative assembly, which included Daniel Boone, Patrick Henry and the governor. The plan was thwarted by an astute young man named Jack Jouett. Although, a few were apprehended, among them Daniel Boone; Jouett’s actions prevented the British from arresting the biggest prize: Governor Thomas Jefferson.

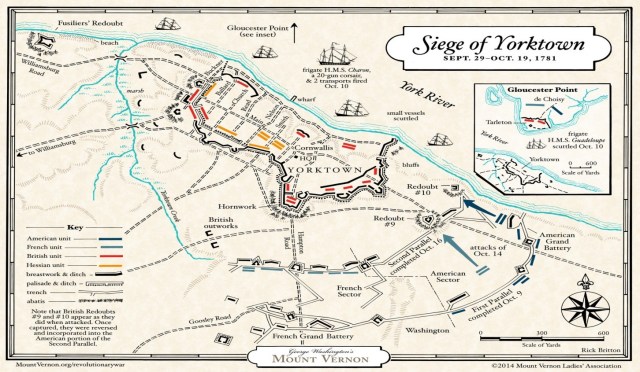

By early August, Cornwallis had made plans to establish fortifications in Yorktown, expecting reinforcements to increase his troops of approximately nine-thousand.

General Washington, in the meantime, had joined forces with Comte de Rochambeau to recapture New York. With intelligence supplied by James Armistead, they learned that Cornwallis was in Yorktown waiting for military support. French Admiral de Grasse, with a fleet of about twenty-eight naval ships, was on his way to the Chesapeake from St. Dominick (present-day Haiti). A plan to surround Cornwallis by land and sea appeared possible. The French naval fleet, along with the Washington’s Continental and Rochambeau’s French forces, headed to the enemy’s headquarters. Once Washington reached Yorktown, General Lafayette’s regiment joined him. Thus, Armistead’s accurate and meticulous reports were vital to the American victory that culminated in Yorktown on October 19, 1781.

Later Cornwallis met the Marquis at his headquarters and was flabbergasted to find his spy James Armistead present.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 severed ties from Britain, the mother country, and established America as an independent nation. That same year, the Act of 1783 was passed freeing slaves who had fought in the Revolutionary War on their masters’ behalf. However, it excluded slave-spies. Ergo, James Armistead, who risked his life by providing information to help win the freedom of many, was himself denied freedom. Was his life in less danger operating under subterfuge as a spy amongst the British than it would have been, had he served as a soldier on the battlefield? I think not. Had his espionage been discovered, he surely would have had to forfeit his life.

After the war, Armistead was returned to slavery. Even his own master didn’t have the legal right to free him because of the Act of 1783, omitting slave-spies from emancipation.

When learning of his compatriot’s status, the Marquis penned a certificate to the Virginia legislator in October of 1784 imploring them to grant Armistead his freedom, declaring:

“This is to Certify that the Bearer By the Name of James Armistead Has done Essential Services to me While I had the Honour to Command in this State. His Intelligences from the Ennemy’s Camp were Industriously Collected and More faithfully deliver’d. He properly Acquitted Himself with Some Important Commissions I Gave Him and Appears to me Entitled to Every Reward his Situation Can Admit of. Done Under my Hand,” Richmond, November 21st 1784.

The legislator didn’t act upon the request straightaway. However, again in 1786, James Armistead applied for his freedom and it was duly granted on January 9, 1787, with a fair compensation to his master, William.

In honor of his benefactor, James Armistead added Lafayette to his surname. After emancipation, he moved a short distance south of New Kent, near Richmond, Virginia and acquired forty acres of less than suitable farmland. He married and had a family. He even owned slaves. History doesn’t tell us if he bought enslaved relatives to free them or if they were bought to farm his land as field hands.

It wasn’t until 1819 that he applied to the state legislature for financial assistance to ease his poverty. This time, the response was immediate; he received $60 and an annual pension of $40 for his service during the Revolutionary War.

Unlike James Armistead Lafayette, many blacks who worked as laborers, guides, messengers and spies were not as fortunate. Whether they were pressed into service or willingly answered the call, most neither received their freedom nor wages for their behind-the-scene contributions to the war.

In 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette visited the United States and was lauded as a hero of the American Revolutionary War in Richmond with festivities and a parade. Spying Armistead in the crowd, it is said he halted the procession, dismounted from his horse and embraced his old comrade.

_____________________________________________________________

End Notes

References:

On this date, in 1781, the British army marched out of their entrenchments at Yorktown and surrendered to General George Washington and the combined Continental and French armies.

Although the victory did not conclusively end the war, the victory prompted British Prime Minister, Lord Frederick North, to exclaim,

“Oh, God, it is all over!”

Approximately two years later, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, the American Revolutionary War was truly over.

What is not truly over is the efforts to preserve, interpret, and educate the current and future generations about the importance of Yorktown and the American Revolution. In the spring, the new American Revolution Museum of Yorktown will open its doors, updating the Victory Center at Yorktown Museum.

From the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation website, the museum’s goals are to;

“Through comprehensive, immersive indoor exhibits and outdoor living history, the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown offers a truly national perspective, conveying a sense of the transformational nature and epic scale of the Revolution and the richness and complexity of the country’s Revolutionary heritage.”

For more information about the museum, what it entails, and the opening date, click here.

Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes back historian Bert Dunkerly. The accounts below come from Mr. Dunkerly’s book on the battle.

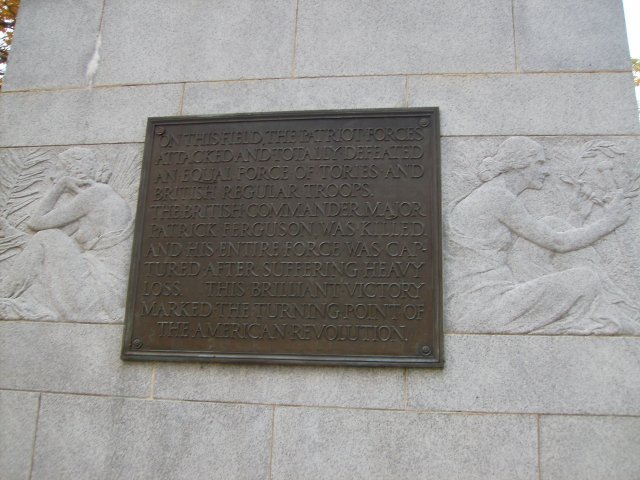

The battle of Kings Mountain was an intense, one-hour battle fought just below the North Carolina-South Carolina border. The October 1780 engagement pitted about 900 American militia from five states (Virginia, the two Carolinas, Georgia, and modern-day Tennessee) against 1,100 Loyalists under Maj. Patrick Ferguson. With Ferguson’s wounding late in the action, command fell to his subordinate, Captain Abraham DePeyster. As the Americans closed in, the Loyalists surrendered.

Eyewitness accounts provide details of the battle, especially its lesser known aspects like the conclusion of the battle and subsequent Loyalist surrender. Here are a few detailed accounts, presented with original spelling and grammar.

Virginia militiaman Leonard Hice had quite an experience in the battle, being wounded four times. He would spend two years recovering:

“I was commanded by Captain James Dysart where I was dreadfully wounded, I received two bullets in my left arm and it was broken. We were fighting in the woods and with the assistance of my commander who would push my bullets down, I shot 3 rounds before I was shot down. I then received a bullet through my left leg. The fourth bullet I received in my right knee which shattered the bone by my right thigh and brought me to the ground. When on the ground I received a bullet in my breast and was bourne off the ground to a doctor.”

Andrew Cresswell was a militiaman from Virginia who found himself too far in front during the final phase of the battle. He also was fortunate to witness the surrender and provided one of the only accounts of Captain Abraham DePeyster surrendering to Colonel William Campbell. His account also speaks to the brutal nature of the fighting between Loyalist and Whig.

“I saw the smoke of their guns and as I saw but one man further round than myself I spoke to him and told him we had better take care least we might make a mistake. I retreated about ten paces where I discharged my gun. About that moment they began to run. I waited for nobody. I ran without a halt till I came to the center of their encampment at which moment the flag was raised for quarters. I saw Capt. DePeyster start from amongst his dirty crew on my right seeing him coming a direct course towards me. I looked round to my left I saw Col. Campbell of Virginia on my left DePeyster came forward with his swoard hilt foremost. Campbell accosted him in these words “I am happy to see you Sir. DePeyster, in answer swore by his maker he was not happy to see him under the present circumstances at the same time delivered up his sword – Campbell received the sword, turned it round in his hand and handed it back telling him to return to his post which he received. Rejoining these words, God eternally damn the Tories to Hell’s Flames and so the scene ended as to the surrender.”

Lt Anthony Alliare was a New York Loyalist in Ferguson’s command. He recounts the experience of the New York detachment, which launched a series of unsuccessful bayonet charges early in the battle. His reference to the “North Carolina regiment” refers to local Loyalist troops fighting alongside his men.

“The action continued an hour and five minutes, but their numbers enabled them to surround us. The North Carolina regiment seeing this, and numbers being out of ammunition, gave way, which naturally threw the rest of the militia into confusion. Our poor little detachment, which consisted of only seventy men when we marched to the field of action, were all killed and wounded by twenty, and those brave fellows were soon crowded as close as possible by the militia.’

Ensign Robert Campbell of Virginia also witnessed the close of the battle, and recounts a white flag being raised.

“It was about this time that Colonel Campbell advanced in front of his men, and climbed over a steep rock close by the enemy’s lines to get a view of their situation and saw they were retreating from behind the rocks that were near to him. As soon as Captain Dupoister observed that Colonel Ferguson was killed, he raised flag and called for quarters. It was soon taken out of his hand by one of the officers on horseback, and raised so high that it could be seen by our line, and the firing immediately ceased. The Loyalists, at the time of their surrender, were driven into a crowd, and being closely surrounded, they could not have made any further resistance.”

Isaac Shelby, from the Carolina frontier (modern Tennessee) was a militia commander in the battle. He also provides insights in the battle’s final moments.

“They were ordered to throw down their arms; which they did, and surrendered themselves prisoners at discretion. It was some time before a complete cessation of the firing, on our part, could be effected. Our men, who had been scattered in the battle, were continually coming up, and continued to fire, without comprehending in the heat of the moment, what had happened; and some, who had heard that at Buford’s defeat the British had refused quarters to many who asked it, were willing to follow that bad example. Owing to these causes, the ignorance of some, and the disposition of other to retaliate, it required some time, and some exertion on the art of the offices, to put an entire stop to the firing. After the surrender of the enemy, our men gave spontaneously three loud and long shouts.”

In one hour, the entire Loyalist force of 1,100 was killed, wounded, or captured. October 7 marks the anniversary of this battle which, in the words of Thomas Jefferson, was the “turn of the tide of success.”

Robert M. Dunkerly (Bert) is a historian, award-winning author, and speaker who is actively involved in historic preservation and research. He holds a degree in History from St. Vincent College and a Masters in Historic Preservation from Middle Tennessee State University. He has worked at nine historic sites, written eleven books and over twenty articles. His research includes archaeology, colonial life, military history, and historic commemoration. Dunkerly is currently a Park Ranger at Richmond National Battlefield Park. He has visited over 400 battlefields and over 700 historic sites worldwide. When not reading or writing, he enjoys hiking, camping, and photography.

Emerging Revolutionary War is honored to welcome historian Malanna Henderson to the blog. A biography of Mrs. Henderson is at the bottom of this post.

Historical records are generally written by men about men.

When most of us think about the role women played in the Revolutionary War, Betsy Ross comes to mind. Why did early historians choose to recognize the contributions of Betsy Ross instead of others? We all know the answer to that question. Her contribution was sewing the American flag. Sewing, a traditional “female” occupation, was elevated to heroic heights by the legacy of Ross. Most historians today don’t name Betsy Ross as the designer of the first American flag, but that’s another story.

Women whose contributions didn’t fall neatly into categories that weren’t exclusively defined as “feminine” were intentionally excluded; and yet, without their contributions, big and small during the years that the war ensued, the war could have raged on longer or dare I say, we might be flying the Union Jack instead of the Stars and Stripes.

Heroism has many forms.

On the home front women maintained the farms, took care of livestock and fed, clothed and educated their children while their husbands took up arms against the British. That was how most women supported the war effort. However, as in the Civil War women were camp followers, accompanying their husbands and sons to the battlefield. For these women, the army could supply food and protection since they could no longer support themselves after their men left for war. In the military camps, women nursed the sick and wounded, laundered and mended uniforms and cooked meals. At some time in the war, women were paid for providing these services.

Then there were women who chose to pursue more daring endeavors, like spying or binding their breast, cutting their hair and donning men’s clothing to enlist in the war under an alias.

One in particular, Deborah Sampson answered the call to freedom by enlisting in the in the 4th Massachusetts Regiment, under the alias Robert Shurtliff. Continue reading “A Woman’s Place –Women’s Contribution in the Revolutionary War”