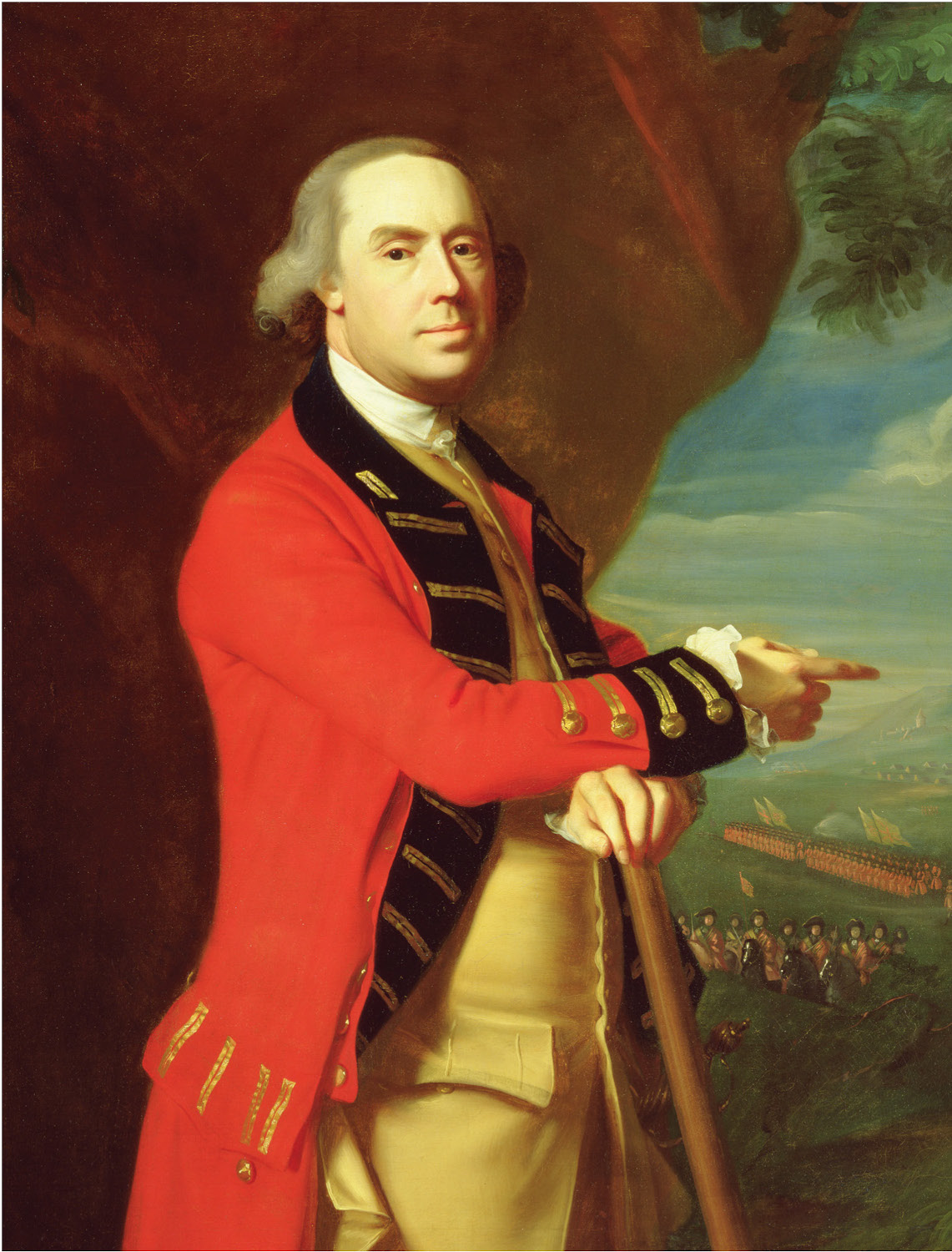

On September 1, 1774 Massachusetts was on the brink of war. General Thomas Gage, now Governor of Massachusetts was growing more worried about Whig access to gunpowder and weapons. He made a fateful decision to send a small expedition to retrieve the provincial powder stored in Charlestown. This powder in Gages’ mind, was owned by the King. Local leaders felt otherwise and now this grab for powder by Gage nearly sparked war in 1774.

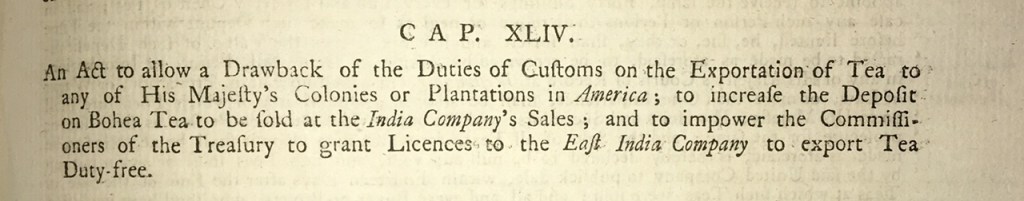

As word of the Boston Tea Party reached the other colonies, the response was mixed. Most colonists believed Bostonians should pay for the ruined tea, but they were also overwhelmingly shocked by the harshness of the Coercive Acts. Support from across the 13 colonies began to pour into Boston. Using an already established “Committee of Correspondence” network created in the early 1770s, colonial leaders began to discuss a proper reaction. Boycotts on imports of British goods and tea especially were accepted broadly. But most importantly, 12 colonies (Georgia abstained) sent representatives to a “Continental Congress” in Philadelphia in September 1774. Unlike the previous Stamp Act Congress, the First Continental Congress was attended by the majority of American colonies. The Congress encouraged boycotts and also petitioned the King and Parliament to rescind the Coercive Acts. In response to their planned attendance, Governor Gage dissolved the Massachusetts Provincial Assembly before the Continental Congress met and called for new elections. This did not deter them from sending representatives (John Adams, Samuel Adams, Thomas Cushing, and Robert Treat Paine) to Philadelphia.

Back in Massachusetts, Gage became wearier of his situation and the possibility of open conflict with colonists. He was active in paying informants and gaining information from local Tories (those loyal to the British government). These sources informed Gage that the people of the countryside were beginning to arm themselves. In an effort to deny them use of the official Royal arms and powder stored across the colony, he began to collect these government-owned supplies. In colonial America, most men served in the local militia. Local towns had powder magazines to store the powder that would be used for training the militia or if the militia was called to defend a portion of the colony. Many of these powder magazines also stored a portion of gunpowder that belonged to the colonial government—the King’s powder.

One such large powder magazine that stored a large quantity of British gunpowder was in nearby Charlestown, now known as Somerville. This powder magazine was the largest in the colony. William Brattle, the commander of the Middlesex County militia and a Royal appointee, notified Gage that he believed the local militia were making plans to steal the Royal gunpowder. Gage moved quickly; he ordered the Middlesex County sheriff to secure the keys. Then early on the morning of September 1, nearly 300 British Regulars made their way to the powder house and removed all of the gunpowder that rightfully belonged to the governor and his agents. By that afternoon, the British troops, powder, and two cannon were in Boston at Castle William (a fort on an island in Boston Harbor).

Word spread quickly that the British came and stole the powder and, in the process, had shot and killed colonials. Now Boston was on fire, and the British navy was bombarding the city. All of this of course was not true, but the word spread like wildfire just the same. Misinformation abounded, and now thousands of locals and militia were gathering in Cambridge looking for revenge. Many loyal to the colonial government were forced to flee to Boston for protection. As time went on, it was evident that the rumors of a battle and Boston burning were untrue. The incident, however, showed how quickly the countryside could mobilize against the governor. Word was quickly sent to Philadelphia where the delegates to the First Continental Congress was aghast at the news. They debated on what to do, and the Massachusetts delegation specifically were on edge for more information. Word eventually arrived that the situation that was first reported was not accurate and no fighting had broken out. John Adams wrote;

“When the horrid news was brought here of the bombardment of Boston, which made us completely miserable for two days, we saw proofs of both the sympathy and the resolution of the continent. War! war! war! was the cry, and it was pronounced in a tone which would have done honor to the oratory of a Briton or a Roman. If it had proved true, you would have heard the thunder of an American Congress.”

Gage, somewhat shaken by the event, began to concentrate his military strength in the city of Boston and fortified the city against a possible attack. He sent word to England that he needed more men to enforce the Coercive Acts. The “Powder Alarm” proved that, within a day, thousands of armed colonials could assemble. The message he sent London shocked the King: “If you think ten thousand men sufficient, send twenty; if one million is thought enough, give two.” Soon after on September 9th, Whig (Patriot) leaders such as Dr. Joseph Warren and others passed the Suffolk Resolves. These strongly worded resolves called for a boycott of British goods and heavily impacted policies adopted by the First Continental Congress. Parliament badly miscalculated the colonial reaction to the Coercive Acts and the pendulum was beginning to swing to independence. The Powder Alarm quickly taught General Gage that the resistance to Royal authority was not just a small group of rebels, but a growing majority of the population.

You can still today visit the the famous Powder House today. It stands in Nathan Tufts Park at 850 Broadway, Somerville, Massachusetts (GPS: N 42.400675, W 71.116998). There is plenty of street parking available. Take the trails in the park to the Powder House located in the center of the park.