Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes guest historian Drew Palmer. A biography follows at the end of this post.

What does it look like when veteran soldiers do not want to fight anymore? When morale plummets and the realities of war take their toll on men. This is exactly what happened to 150 men in the Maryland Line of the Continental Army in the late summer of 1780.

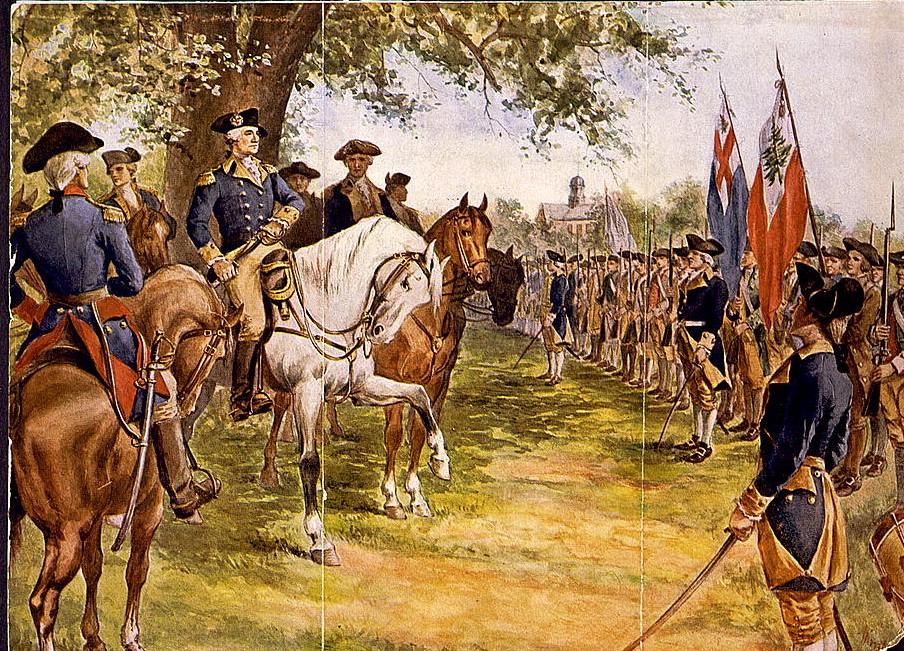

The continental regiments of Maryland that made up what became known as the “Maryland Line” or “Old Line State” had earned the reputation as a reliable, brave, and disciplined fighting force as early as 1776 after their actions in the Battle of Long Island.1 At the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780, the 1st and 2nd Maryland Brigades offered a stout defense as Gen. Charles Cornwallis’s British force crashed into Continental soldiers from Maryland and Delaware. In the end, though, Maj. General Horatio Gates’s Southern Continental Army was completely routed from the field, with many of the Maryland Continental troops taken prisoner and held in the small village of Camden after the battle.2

The village of Camden, South Carolina, was an unpleasant place to be after the battle. The crowded conditions and brutal summer climate of South Carolina began to produce sickness amongst Cornwallis’s men and the American prisoners that were held in Camden. To prevent further sickness from spreading, Cornwallis decided to split the American prisoners held at Camden into divisions of around 150 men. These divisions were guarded by small detachments of the British army and marched from Camden to Charlestown, South Carolina.3 One detachment of the British 63rd Regiment of Foot escorted 150 prisoners of the 1st Maryland Brigade captured at Camden. The division made it to Thomas Sumter’s abandoned plantation at Great Savannah, about 60 miles northwest of Charleston. As the Maryland prisoners and their British guards halted for the night, militia commander Francis Marion received word from a Loyalist deserter that the Marylanders were nearby and decided to ambush the British element in hopes of freeing the Maryland prisoners.4 In the early morning hours of August 25, 1780, Marion’s militia attacked.

Continue reading “The Breaking of Maryland’s “Old Line””