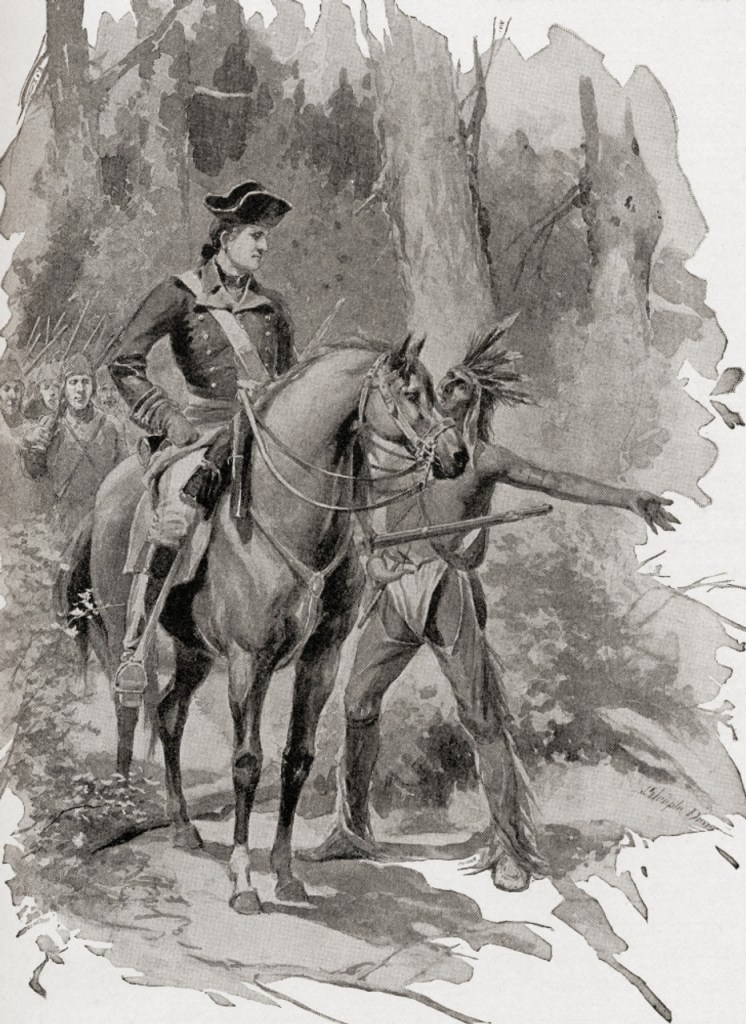

On this date in 1754, a young George Washington penned the letter below to Thomas Cresap explaining the difficulties of procuring supplies for the Virginian’s expedition to the Ohio River Valley. His main objective was to fortify the land at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers – the “Forks of the Ohio.” The several hundred mile expedition would have to be made over treacherous terrain and through vast wildernesses, which meant a road needed to be cleared that could carry men, animals, and wagons. Years before, Cresap, while serving as an agent for the Ohio Company, had widened an old Indian trail leading to the west. Washington planned to utilize and improve this same route. That same day, he and 159 men under his command departed Winchester, Virginia, and began their march. Over a month later, they would fire the first shots of the French and Indian War at Jumonville Glen.

“Sir

The difficulty of getting Waggons has almost been insurmountable, we have found so much inconvenience attending it here in these roads that I am determined to carry all our provisions &c. out on horse back and should be glad if Capt. Trent with your Assistance would procure as many horses as possible against we arrive at Wills Creek that as little stoppage as possible may be made there. I have sent Wm Jenkins with 60 Yrds of Oznabrigs [Osnaburg] for Bags and hope you will be as expeditious as you can in getting them made and fill’d.

Majr Carlyle acquainted ⟨me⟩ that ⟨a number of kettles, tomhawks, best gun flints, and axes might be had⟩ from the Companys Store which we are much in ⟨want and s⟩hould be glad to have laid by ⟨for us, Hoes we sh⟩all also want, and several pair of Hand cuffs.

I hope all the Flower [flour] you have or can get you will save for this purpose and other provisions and necessary’s which you think will be of use (that may not occur to my memory at present) will be laid by till our Arrival which I expect will be at Job Pearsalls [20 miles from Wills Creek] abt Saturday night or Sunday next, at present I have nothing more to add than that I am Yr most Hble Servt

Go: Washington[i]“

[i] “From George Washington to Thomas Cresap, 18 April 1754,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-01-02-0042. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 1, 7 July 1748 – 14 August 1755, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, pp. 82–83.]