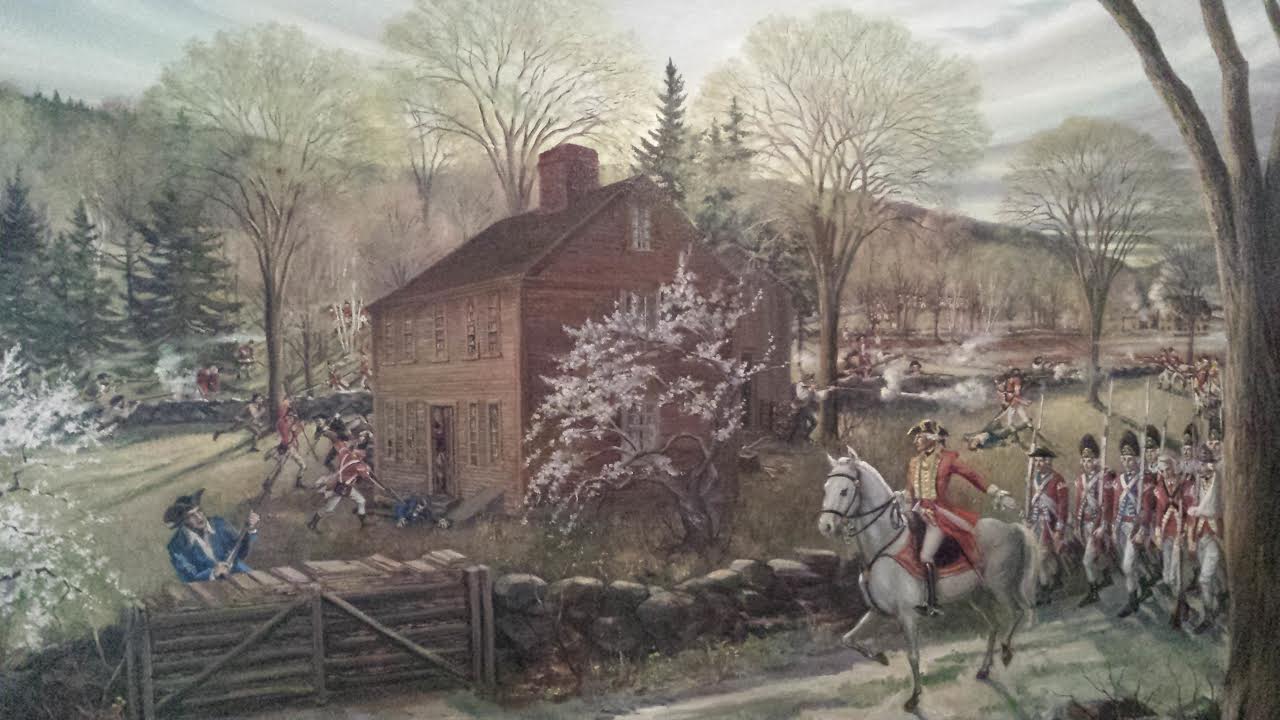

In December 1775, Henry Knox wrote to General George Washington, “I hope in 16 or 17 days to be able to present your Excellency a noble train of artillery”. However, the train of artillery would not arrive until the end of January 1776. Still an impressive feat, as Knox with his team moved 60 tons (119,000 pounds) of artillery over 300 miles from upstate New York to the environs of Boston in 70 days in the midst of winter.

This impressive feat enabled Washington to evict the British from Boston, winning the siege and giving the fledgling rebellion a victory to build momentum from.

To discuss this amazing feat and part of American military history, Emerging Revolutionary War welcomes Dr. Phillip Hamilton, a professor of history at Christopher Newport University. A historian of the American Revolutionary and Early Republican periods, he has edited and written “The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox.”

Although the program is pre-recorded, Emerging Revolutionary War hopes you still tune in on Sunday, February 22 at 7 p.m. EDT. We promise the revelry will be enlightening. If you have any questions, please drop them in the chat during the program, and we will ensure Dr. Hamilton receives them.