By the evening of January 6, 1781, much of the small town of Richmond, newly appointed capital of Virginia, was in flames. Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold and his force of British regulars and loyalist provincial troops, to the tune of around 800, were east of the city, heading toward Westover Plantation, in Charles City County. It was the home of Mary Willing Byrd, widow of the late William Byrd III. She was also a cousin to Arnold’s wife, Peggy Shippen Arnold. The British transports had landed at Westover back on January 4 and it was there that Arnold finished planning his march on Richmond, 25 miles away.

Westover Plantation

With the arrival of Arnold’s forces at Portsmouth, on the Virginia coast, Gov. Thomas Jefferson believed the target of the raid was Williamsburg. Baron Friedrich von Steuben, the Continental Army’s military commander in the area, believed Petersburg was at risk. Both men were surprised when Arnold landed at Westover, showing his target clearly to be Richmond. Caught off guard, Jefferson nevertheless swung into action, calling out local militia companies. Von Steuben, likewise, sent Continental forces he had on hand to the north side of the James River, to relieve the capital. With a price on his head, the traitor Benedict Arnold couldn’t afford to linger too long in the area. Were he to be captured, he knew it would mean the gallows for him. After spending a mere 24 hours in the city, destroying Westham Foundry, located six miles above Richmond, burning public buildings & filling 42 small craft with tobacco, rum, and any other commodity worth cash money he could find, he gave the order to return to Westover and his troop transports.

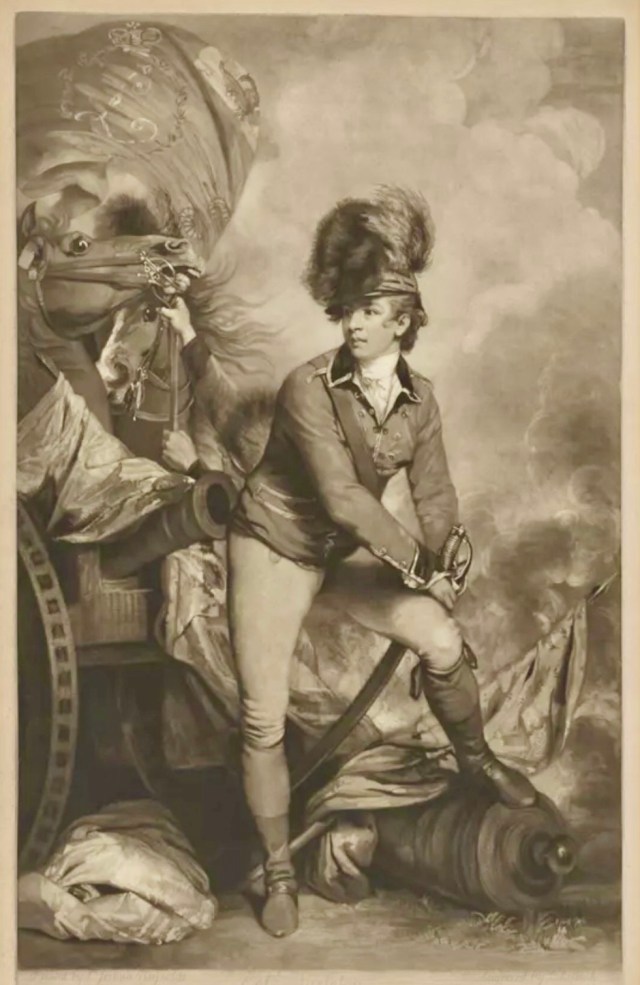

Arriving there on January 7, the bulk of Arnold’s troops immediately bivouacked & began cooking rations. With Jefferson’s call, though, Patriot militiamen from the lower counties had been gathering throughout the area of Charles City. Many were seen on the high ground in back of Westover Plantation. Arnold became desperate for intelligence. Among his provincial forces were the Queen’s Rangers, Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe, commanding. Made up mostly of loyalists from New York, the Queen’s Rangers were comprised of well trained and equipped light infantry and cavalry troops. Back on January 5th, it had been Simcoe who had led the troops who destroyed Westham Foundry. Born in England, Simcoe had served throughout the war, beginning with the siege of Boston back in 1775. He was a very competent officer who would go on after the war to serve as the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada & to be elected a member of Parliament. He kept a journal throughout the war which he first published in 1787. In this journal Simcoe described the action in Charles City, after the raid on Richmond.

Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe

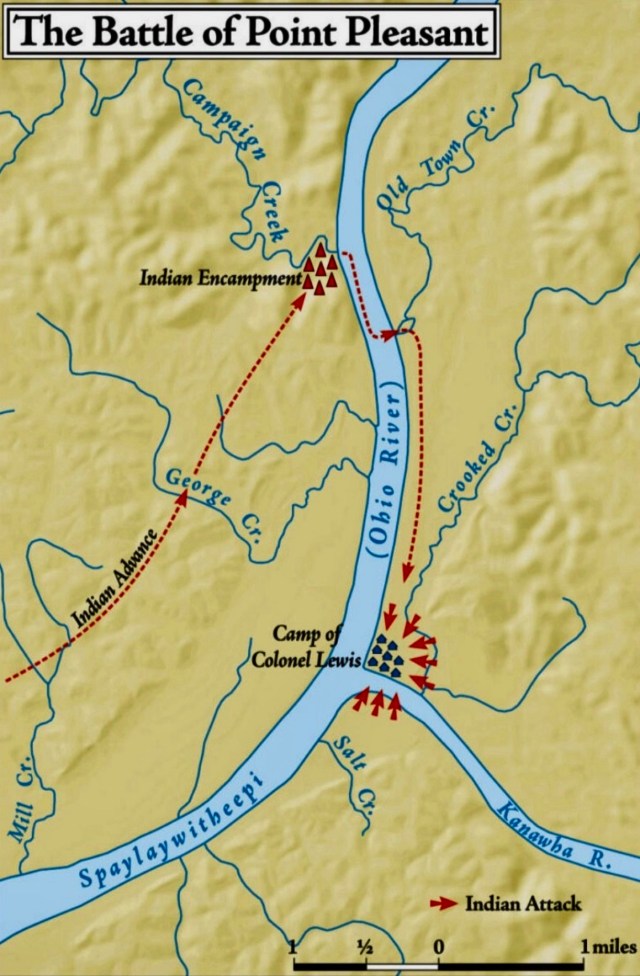

Gen. Arnold ordered him to lead a patrol, he said, “to be made on the night of the eighth of January towards Long Bridge (on the Chickahominy River) in order to procure intelligence.” Simcoe detached 40 of his cavalrymen for the patrol. For the most part, he said, his men were “badly mounted, on such horses as had been picked up in the country.” The patrol had not proceeded beyond 2 miles on the main road, presumably the River Road (Modern Virginia State Route 5) before Simcoe’s vidette, a Sergeant Kelly, was challenged by two Patriot militiamen. Kelly kept up a friendly demeanor until he came close, then he rushed the Patriot scouts. He captured one while the other fled. Along with one prisoner, Simcoe said he also freed “a Negro who had been taken on his way to the British army.” From the rebel prisoner he learned that Patriot general Thomas Nelson, Jr had a large party of militiamen encamped at Charles City Courthouse, about 6 miles to the east. The corps of militiamen that had been seen at Westover were an advance party, the captured Patriot had said, and numbered around 400.

Upon learning this, Simcoe says he immediately ordered his troopers to the “right about”, off the road. A Lt. Holland, “who was similar in size to the vidette who had been taken” led the Ranger’s advance. The African American man Simcoe liberated offered to guide his force to the courthouse by an obscure pathway, off the main road. Simcoe’s intention was to attack or, in his words, “beat up” the main body of militia at the courthouse, believing their guard would be lowered owing to the presence of the large advance party on the main road. If repulsed, he planned to retreat along the same path. If successful against the main body, though, he knew he had the option of attacking that advance party of 400 men.

Charles City Courthouse, built ca 1730

As they moved to the east that evening, Simcoe wrote that the patrol “passed through a wood”, where it halted “to collect”. They had scarcely resumed their march on this back road when the column was immediately challenged by a Patriot picket or vidette. Answering the challenge, Lt. Holland, riding in the van, immediately called out… “A friend”; he then gave the countersign for the challenge which the Patriot prisoner had told them. “It is I, me, Charles.”, which apparently was the name of the Patriot militiamen whom Lt. Holland was impersonating. Holland continued leading the column, past the first picket. Riding beside him was the irrepressible Sergeant Kelly, who immediately grabbed the militiaman. Holland himself lunged for a second militiaman who was sitting his horse nearby, but Simcoe said, grabbing hold of him the man was too strong and got free. That second man whirled and, “presented, and snapped his carbine.” For Lt. Holland it was a lucky misfire. The militiaman then galloped off a distance, re-primed his piece & fired off a warning shot.

Simcoe’s patrol had been spotted; the element of surprise was now lost. He gave the immediate order to advance as rapidly as possible and very quickly his force reached the grounds of the courthouse where several companies of Patriot militiamen were encamped. To these men, this had always been a place of safety; where men of Charles City County came to join the militia and, many years later, this is where many old veterans would file their depositions in hopes of obtaining a pension for their service. Now, they were under attack. According to militiaman William Seth Stubblefield, his company was “taken on surprise” about midnight. Simcoe said his men rushed on and immediately a confused and scattered fire began, on all sides. His troopers, attacking from out of the darkness, were nonetheless heavily outnumbered. Thinking quickly, however, Simcoe used his cunning.

Queen’s Rangers

He immediately sent his two “bugle horns”, buglers, men he called French and Barney, over towards his right. They had orders to “answer his challenging, and sound when he ordered.” The night air was quickly becoming filled with lead as both sides exchanged fire. As a ruse, Simcoe called out in a loud voice for the “Light Infantry to form”; then he gave the order to “sound the advance”. The buglers on the right responded, and sounded their horns. In a matter of seconds, the Patriot militiamen, caught off guard and now apparently fooled into thinking they were outnumbered and being flanked, immediately started falling back. As John Graves Simcoe described it, “the enemy fled on all sides, scarcely firing another shot.” And just like that, the skirmish was over. But the night was dark, and the Queen’s Rangers were unfamiliar with the country. Some of the Patriots were captured while others were wounded. Simcoe said a few of the fleeing militiamen drowned in a nearby mill dam. In his 1833 pension application, militiaman Irby Phillips likewise referenced men “drowning in a mill pond”. Simcoe said that he himself stepped in to save three armed Patriots from “the fury of the soldiers (Rangers)”. He said the militiamen were frightened and presented their loaded pieces, directly at his breast. In their agitated state, they easily could have pulled the triggers, but, luckily for Simcoe, they didn’t.

From these three prisoners he learned that he had earlier been deceived; that he had fallen for a ruse himself. The story he had been told of the 400-man Patriot advance party near the main road was false; there was no advance party. What Simcoe had been calling the main party consisted of between 150 and 200 militiamen, all encamped with cookfires going. General Nelson was not among them but, apparently, was in camp some miles away, back towards Williamsburg with a force of around 700 or 800. Many of the fleeing militiamen headed in that direction.

Simcoe ordered his troopers to mount immediately. Many of them wanted to search the buildings and homes near the courthouse, where several of the militiamen had fled, but were not permitted. Simcoe wrote that his troopers were “plainly distinguished by the fires which the enemy had left.” Silhouetted in this way, the commander believed his small numbers could have easily been discerned, possibly inviting a dangerous counter attack.

In this brief action, the Queen’s Rangers lost one man, a Sergeant Adams, who was mortally wounded. Simcoe described the sergeant’s last moments: “This gallant soldier, sensible of his situation, said: ‘My beloved Colonel, I do not mind dying, but for God’s sake, do not leave me in the hands of the rebels.” French, one of the buglers, and two other troopers were wounded in the engagement and about a dozen of his horses had been captured. The Patriots, in Simcoe’s estimation, suffered around 20 or so casualties, including several captured.

The Rangers left Charles City Courthouse and headed west, back towards Westover, with their prisoners. Simcoe said the enemy made no threat against his rear. The patrol arrived at Westover the next morning, January 9. There, Sergeant Adams died and was buried with honors. On January 10, Benedict Arnold’s transports shoved off into the James River and began their trip back towards Portsmouth.

By 1781, Virginia was a major supply depot and logistical hub for the Southern American army operating in the Carolinas. While Arnold’s strategic strike against Richmond was brief, it was yet overwhelmingly successful. Ironically though, the final chapter of this event wasn’t written in Richmond at all but, rather, in Charles City. The old county courthouse, which still stands today along historic and scenic Virginia State Route 5, was a witness to it all.