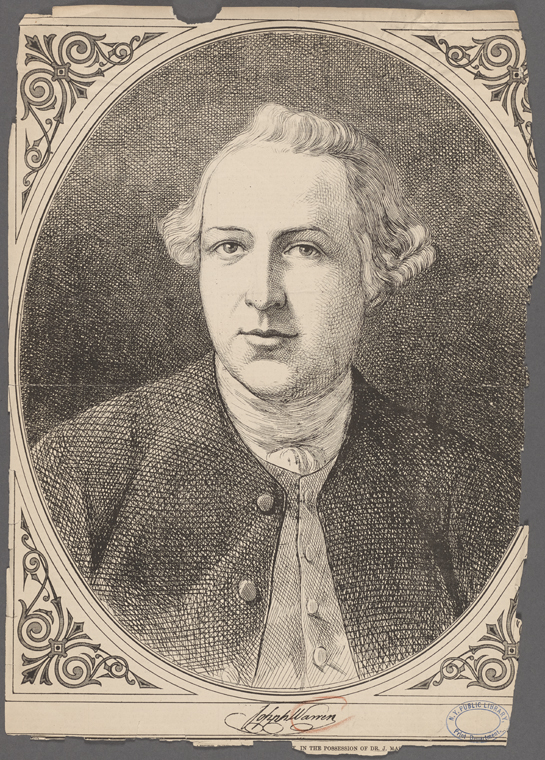

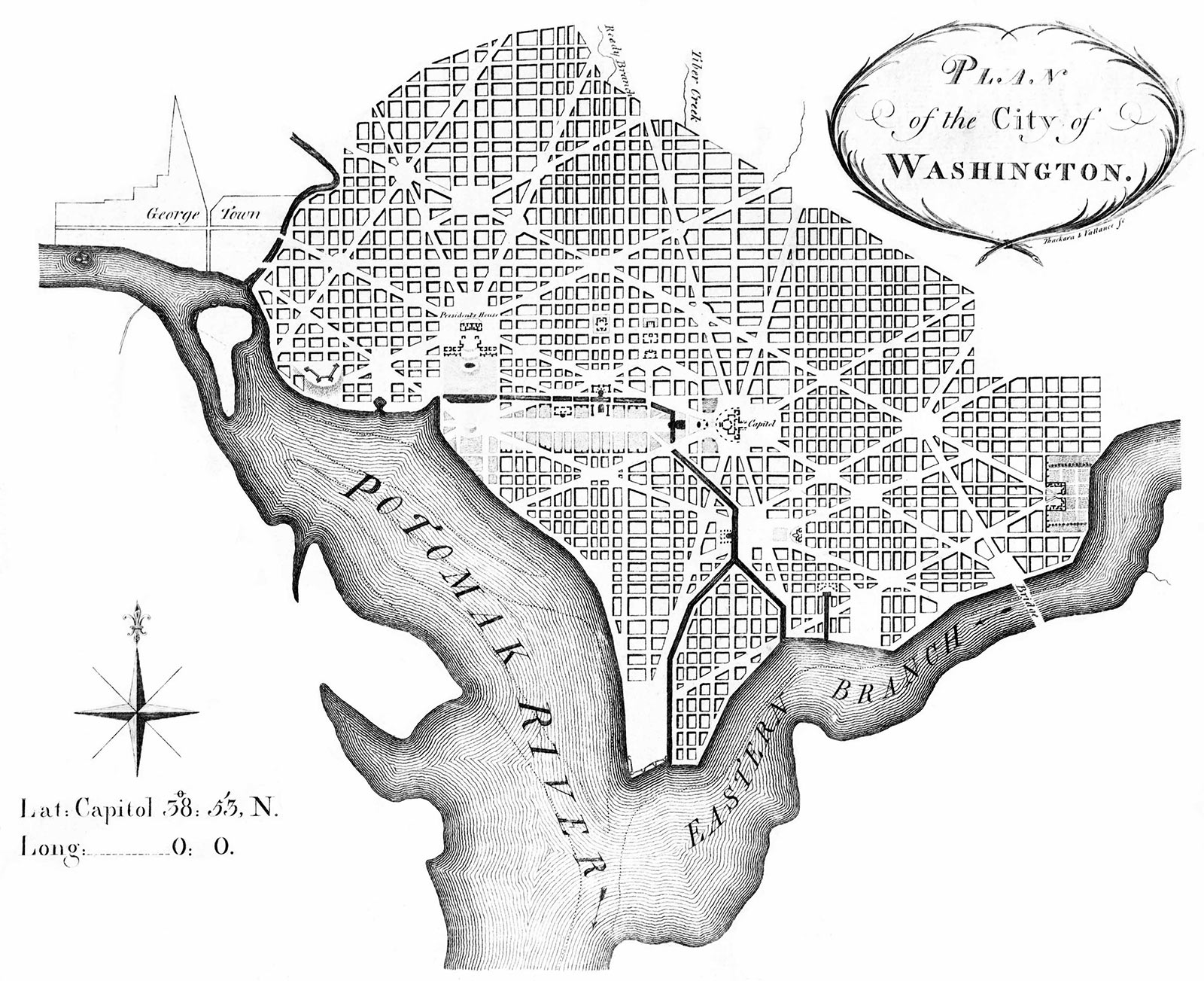

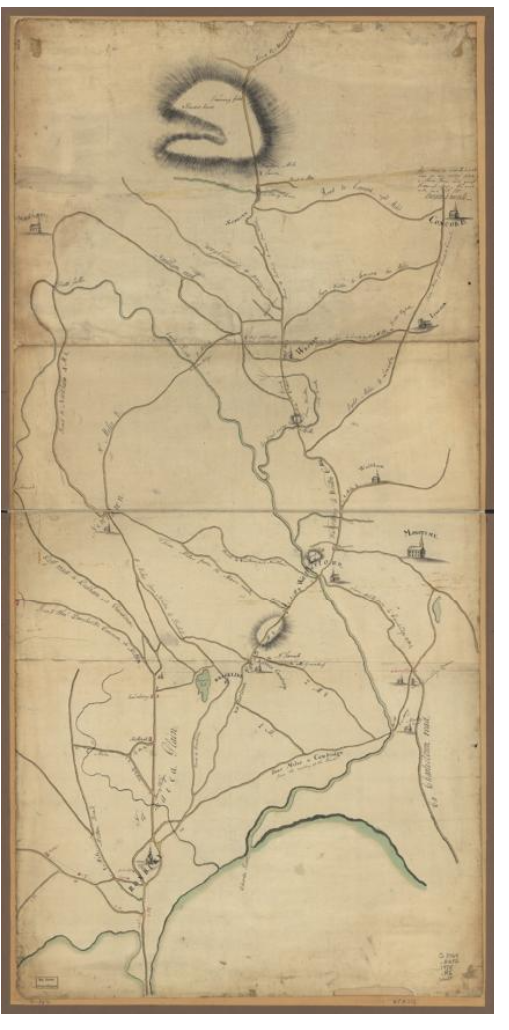

The spy network of Dr. Joseph Warren and the Sons of Liberty is well documented and written about. Few things happened in and around Boston that Warren, Paul Revere or Sam Adams were not aware of. In the winter of 1775, British General Thomas Gage also established a spy network (one of the more famous British spies was supposed “Patriot” Dr. Benjamin Church was not revealed as spy until October 1775). Gage was using all the resources at his disposal to figure out what the Whigs were doing and to find out where weapons (and four cannon that were stolen from the British in Boston) were located. On February 22nd, Gage sent out two officers, Captain John Brown and Ensign Henry De Berniere, to covertly ride out towards Worcester to locate stores and to map the road network for a possible British excursion. A few weeks later, on March 20th Gage sent out Brown and De Berniere again to map out routes towards Concord. Keeping in mind of potential geographic features that could endanger the future British column.

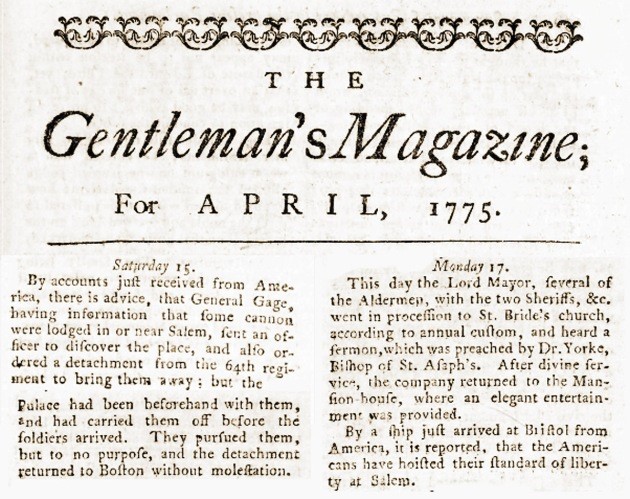

The following is an account of the March 20th mission by Ensign De Berniere. This account was found in Boston after the British evacuated and published by Boston printer J. Gill in 1779. Today it is located in the Massachusetts Historical Society. This mission was the precursor for the April 18-19th British raid to Concord that ignited the war.

Account of the proceedings of the aforesaid officers, in

consequence of further orders and instructions from

General Gage, of the 20th March following ; with

occurrences during their mission.

1779, Massachusetts Historical Society

THE twentieth of March Captain Brown and

myself received orders to set out for Concord,

and examine the road and situation of the

town ; and also to get what information we

could relative to what quantity of artillery and provi-

sions. We went through Roxbury and Brookline, and

came into the main road between the thirteen and four-

teen mile-stones in the township of Weston ; we went

through part of the pass at the eleven mile-stone, took

the Concord road, which is seven miles from the main

road. We arrived there without any kind of insult

being offered us, the road is high to the right and low

to the left, woody in most places, and very close and

commanded by hills frequently. The town of Concord

lies between hills that command it entirely ; there is

a river runs through it, with two bridges over it, in

summer it is pretty dry ; the town is large and co-

vers a great tract of ground, but the houses are not

close together but generally in little groups. We were

informed that they had fourteen pieces of cannon (ten

iron and four brass) and two cohorns, they were mounted but in so bad a manner that they could not elevate them more than they were, that is, they were fixed to one

elevation ; their iron cannon they kept in a house in town, their brass they had concealed in some place behind the town, in a wood. They had also a store of flour, fish, salt and rice ; and a magazine of powder and cartridges. They fired their morning gun, and mounted a guard of ten men at night. We dined at the house of a Mr. Bliss, a friend to government ; they had sent him word they would not let him go out of town alive that morning ; however, we told him if he would come with us we would take care of him, as we were three and all well armed, — he consented and told us he could shew us another road, called the Lexington road. We set out and crossed the bridge in the town, and of consequence left the town on the contrary side of the river to what we entered it. The road continued very open and good for six miles, the next five a little inclosed, (there is one very bad place in this five miles) the road good to Lexington. You then come to Menotomy, the road still good ; a pond or lake at Menotomy. You then leave Cambridge on your right, and fall into the main road a little below Cambridge, and so to Charlestown ; the road is very good almost all the way.

In the town of Concord, a woman directed us to Mr. Bliss‘s house ; a little after she came in crying, and

told us they swore if she did not leave the town, they would tar and feather her for directing Tories in their road.

[Left in town by a British Officer previous to the evacua tion of it by the enemy, and now printed for the

information and amusement of the curious.]

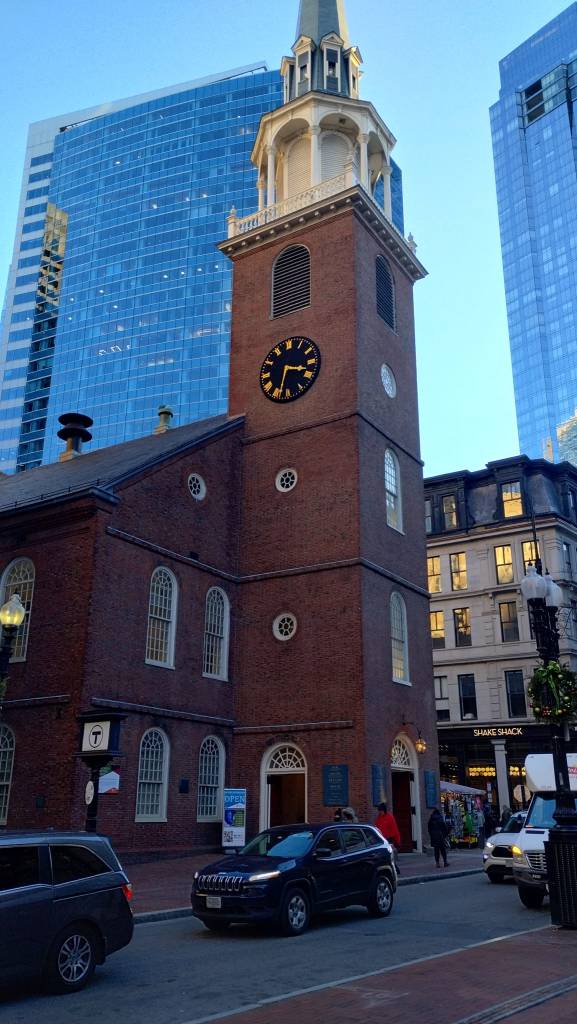

BOSTON

Printed, and to be sold, by J. GILL, in Court Street.

1779.

Massachusetts Historical Society